about Reading Aren’t Teaching Aren’t Learning May 2006

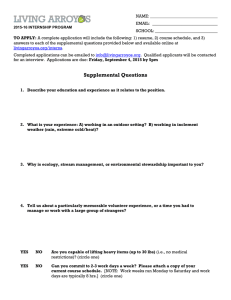

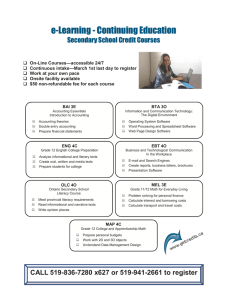

advertisement