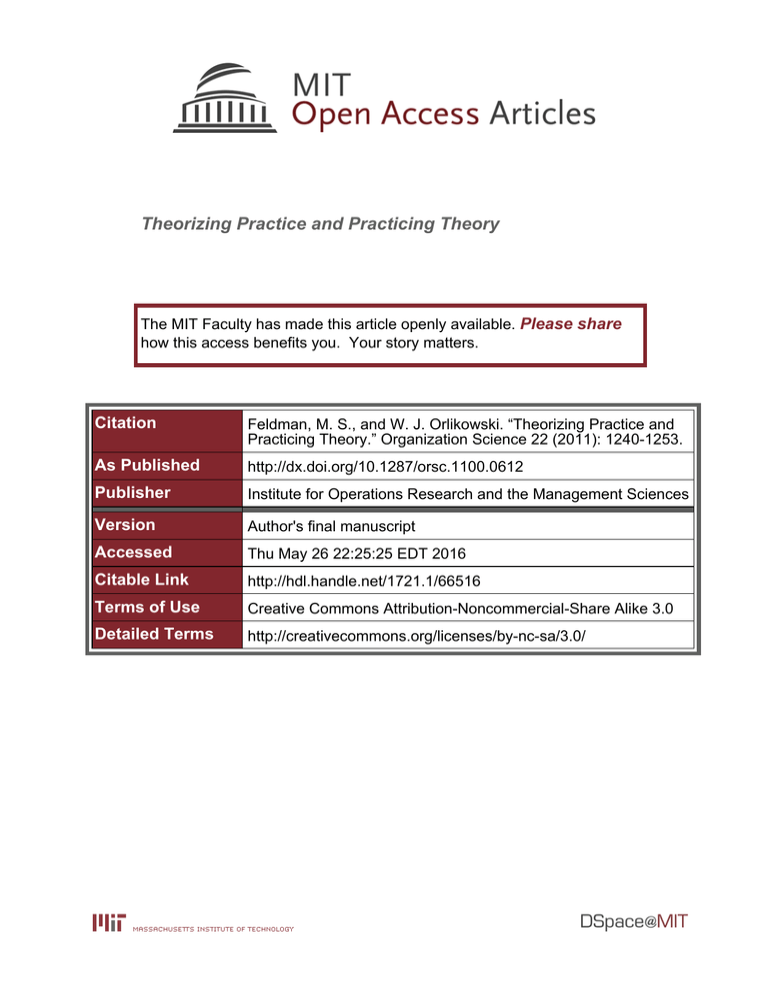

Theorizing Practice and Practicing Theory Please share

advertisement