Document 12534261

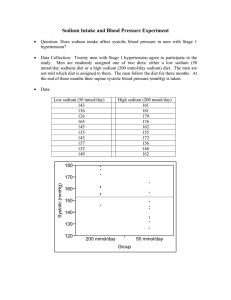

advertisement