N C F G

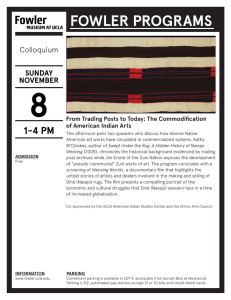

advertisement