Navajo Nation Government Reform Project Diné Policy Institute Prepared By Diné College

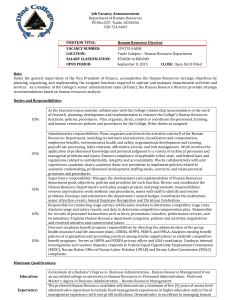

advertisement