ANGLE MODULATION 1. PHASE AND FREQUENCY MODULATION

advertisement

[4.1]

ANGLE MODULATION

1. PHASE AND FREQUENCY MODULATION

For angle modulation, the modulated carrier is represented by

U

𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝐴𝐴 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐[𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 + 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)]

(1.1)

Where A and ωc are constants and the phase angle 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡) is a function of the message

signal m(t). Equation (1.1) can be written as

𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝐴𝐴 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐 𝜃𝜃(𝑡𝑡)

𝜃𝜃(𝑡𝑡) = 𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 + 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)

where

The instantaneous radian frequency of xc(t), denoted by ωi is

𝜔𝜔𝑖𝑖 =

𝑑𝑑 𝜃𝜃(𝑡𝑡)

𝑑𝑑 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)

= 𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 +

𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑

𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑

𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡) = instantaneous phase deviation.

(1.2)

𝑑𝑑 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)

= instantaneous frequancy deviation.

𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑

The maximum (or peak) radian frequency deviation of the angle-modulated signal

(∆ω) is given by

Δ𝜔𝜔 = |𝜔𝜔𝑖𝑖 − 𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 |𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚

(1.3)

In phase modulation (PM) the instantaneous phase deviation of the carrier is

proportional to the message signal; that is,

𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡) = 𝑘𝑘𝑝𝑝 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡)

(1.4)

where kp is the phase deviation constant, expressed in radians per unit of m(t).

In frequency modulation (FM), the instantaneous frequency deviation of the carrier is

proportional to the message signal; that is,

𝑑𝑑 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)

= 𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡)

(1.5𝑎𝑎)

𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑

𝑡𝑡

𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡) = 𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓 ∫−∞ 𝑚𝑚(𝜆𝜆) 𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑

or

thus, we can express the angle-modulated signal as

𝑥𝑥𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑃 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝐴𝐴 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐 [𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 + 𝑘𝑘𝑃𝑃 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡)]

𝑡𝑡

𝑥𝑥𝐹𝐹𝐹𝐹 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝐴𝐴 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐 �𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 + 𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓 � 𝑚𝑚(𝜆𝜆) 𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑�

From Eq.(1.2),we have

−∞

(1.5𝑏𝑏)

(1.6)

(1.7)

Dr. Ahmed A. Alrekaby

[4.2]

𝜔𝜔𝑖𝑖 = 𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 + 𝑘𝑘𝑝𝑝

𝑑𝑑 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡)

𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑

𝜔𝜔𝑖𝑖 = 𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 + 𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡)

𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓 𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑃

𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓 𝐹𝐹𝐹𝐹

(1.8)

(1.9)

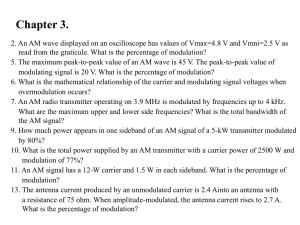

Thus, in PM, the instantaneous frequency 𝜔𝜔𝑖𝑖 varies linearly with the derivative of the

modulating signal, and in FM, 𝜔𝜔𝑖𝑖 varies linearly with the modulating signal. Figure

(1.1) illustrates AM, FM, and PM waveforms produced by a sinusoidal message

waveform.

Fig.(1.1)

2. FOURIER SPECTRA OF ANGLE-MODULATED SIGNALS

An angle-modulated carrier can be represented in exponential form by writing

Eq.(1.1) as

𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝑅𝑅𝑅𝑅�𝐴𝐴 𝑒𝑒 𝑗𝑗 �𝜔𝜔 𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡+𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)� � = 𝑅𝑅𝑅𝑅�𝐴𝐴 𝑒𝑒 𝑗𝑗 𝜔𝜔 𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 𝑒𝑒 𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗 (𝑡𝑡) �

(2.1)

𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗 (𝑡𝑡)

Expanding 𝑒𝑒

in a power series yields

U

𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝑅𝑅𝑅𝑅 �𝐴𝐴𝑒𝑒 𝑗𝑗 𝜔𝜔 𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 �1 + 𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗(𝑡𝑡) −

𝜙𝜙 2 (𝑡𝑡)

𝜙𝜙 𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡)

− ⋯ + 𝑗𝑗 𝑛𝑛

+ ⋯ ��

2!

𝑛𝑛 !

𝜙𝜙 2 (𝑡𝑡)

𝜙𝜙 3 (𝑡𝑡)

= 𝐴𝐴 �𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐 𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 − 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 −

𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 +

𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 + ⋯ � (2.2)

2!

3!

Thus the angle-modulated signal consists of an unmodulated carrier plus various

amplitude-modulated terms, such as 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠 ω𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡, 𝜙𝜙 2 (𝑡𝑡)𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐 ω𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 , 𝜙𝜙 3 (𝑡𝑡)𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠 ω𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 ... ,

etc. Hence its Fourier spectrum consists of an unmodulated carrier plus spectra of

𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡), 𝜙𝜙 2 (𝑡𝑡), 𝜙𝜙 3 (𝑡𝑡),... , etc., centered at ωc.

It is clear that the Fourier spectrum of an angle-modulated signal is not related to the

message signal spectrum in any simple way, as was the case in AM.

Dr. Ahmed A. Alrekaby

[4.3]

3. NARROWBAND ANGLE MODULATION

If |𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)|𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚 ≪ 1, then Eq. (2.2) can be approximated by [neglecting all higherpower terms of 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)]

(3.1)

𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) ≈ 𝐴𝐴𝐴𝐴𝐴𝐴𝐴𝐴𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 − 𝐴𝐴𝐴𝐴(𝑡𝑡)𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡

𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) in Eq.(3.1) is called the narrowband (NB) angle-modulated signal. Thus,

𝑥𝑥𝑁𝑁𝑁𝑁𝑁𝑁𝑁𝑁 (𝑡𝑡) ≈ 𝐴𝐴𝐴𝐴𝐴𝐴𝐴𝐴𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 − 𝐴𝐴𝑘𝑘𝑝𝑝 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡)𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡

(3.2)

U

𝑡𝑡

𝑥𝑥𝑁𝑁𝑁𝑁𝑁𝑁𝑁𝑁 (𝑡𝑡) ≈ 𝐴𝐴𝐴𝐴𝐴𝐴𝐴𝐴𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 − 𝐴𝐴 �𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓 � 𝑚𝑚(𝜆𝜆) 𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑� 𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡

−∞

(3.3)

Equation (3.1) indicates that a narrowband angle-modulated signal contains an

unmodulated carrier plus a term in which 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡) [a function of m(t)] multiplies a π/2

(rad) phase-shifted carrier. This multiplication generates a pair of sidebands, and if

𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡) has a-bandwidth WB, the bandwidth of an NB angle-modulated signal is 2WB.

4. SINUSOIDAL (OR TONE), MODULATION

If the message signal m(t) is a pure sinusoid, that is,

𝑎𝑎 𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝜔𝜔𝑚𝑚 𝑡𝑡

𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓 𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑃

𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡) = � 𝑚𝑚

𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓 𝐹𝐹𝐹𝐹

𝑎𝑎𝑚𝑚 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝜔𝜔𝑚𝑚 𝑡𝑡

then Eqs. (1.4) and (1.5b) both give

𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡) = 𝛽𝛽 𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝜔𝜔𝑚𝑚 𝑡𝑡

(4.1)

Where

𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓 𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑃

𝑘𝑘𝑝𝑝 𝑎𝑎𝑚𝑚

𝛽𝛽 = �𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓 𝑎𝑎𝑚𝑚

(4.2)

𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓 𝐹𝐹𝐹𝐹

𝜔𝜔𝑚𝑚

The parameter β is known as the modulation index for angle modulation and is the

maximum value of phase deviation for both PM and FM. Note that β is defined only

for sinusoidal modulation and it can be expressed as

Δ𝜔𝜔

𝛽𝛽 =

(4.3)

𝜔𝜔𝑚𝑚

Substituting Eq. (4.1) into Eq. (1.1), we obtain

𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝐴𝐴 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐[𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 + 𝛽𝛽 𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝜔𝜔𝑚𝑚 𝑡𝑡]

(4.4)

which can be expressed as

𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝐴𝐴 𝑅𝑅𝑅𝑅(𝑒𝑒 𝑗𝑗 𝜔𝜔 𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 𝑒𝑒 𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗 𝜔𝜔 𝑚𝑚 𝑡𝑡 )

(4.5)

𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗 𝜔𝜔 𝑚𝑚 𝑡𝑡

The function 𝑒𝑒

is clearly a periodic function with period 𝑇𝑇𝑚𝑚 = 2𝜋𝜋⁄𝜔𝜔𝑚𝑚 . It

therefore has a Fourier series representation

U

U

𝑒𝑒 𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗 𝜔𝜔 𝑚𝑚 𝑡𝑡

U

∞

= � 𝑐𝑐𝑛𝑛 𝑒𝑒 𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗 𝜔𝜔 𝑚𝑚 𝑡𝑡

𝑛𝑛 =−∞

The Fourier coefficients cn can be found to be

𝜔𝜔𝑚𝑚 𝜋𝜋 ⁄𝜔𝜔 𝑚𝑚 𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗 𝜔𝜔 𝑡𝑡 −𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗 𝜔𝜔 𝑡𝑡

𝑚𝑚 𝑒𝑒

𝑚𝑚 𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑

𝑐𝑐𝑛𝑛 =

�

𝑒𝑒

2𝜋𝜋 −𝜋𝜋 ⁄𝜔𝜔 𝑚𝑚

Setting 𝜔𝜔𝑚𝑚 𝑡𝑡 = 𝑥𝑥, we have

Dr. Ahmed A. Alrekaby

[4.4]

1 𝜋𝜋 𝑗𝑗 (𝛽𝛽𝛽𝛽𝛽𝛽𝛽𝛽𝛽𝛽 −𝑛𝑛𝑛𝑛 )

𝑐𝑐𝑛𝑛 =

� 𝑒𝑒

𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑 = 𝐽𝐽𝑛𝑛 (𝛽𝛽)

2𝜋𝜋 −𝜋𝜋

Where 𝐽𝐽𝑛𝑛 (𝛽𝛽)is the Bessel function of the first kind of order n and argument β. These

functions are plotted in Fig.(4.1) as a function of n for various values of β.

Note that :

1. 𝐽𝐽−𝑛𝑛 (𝛽𝛽) = (−1)𝑛𝑛 𝐽𝐽𝑛𝑛 (𝛽𝛽)

2𝑛𝑛

2. 𝐽𝐽𝑛𝑛−1 (𝛽𝛽) + 𝐽𝐽𝑛𝑛+1 (𝛽𝛽) = 𝐽𝐽𝑛𝑛 (𝛽𝛽)

3.

Thus

2

∑∞

𝑛𝑛=−∞ 𝐽𝐽𝑛𝑛 (𝛽𝛽)

=1

𝛽𝛽

∞

𝑒𝑒 𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗 𝜔𝜔 𝑚𝑚 𝑡𝑡 = � 𝐽𝐽𝑛𝑛 (𝛽𝛽)𝑒𝑒 𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗 𝜔𝜔 𝑚𝑚 𝑡𝑡

𝑛𝑛=−∞

Substituting Eq.(4.6) into Eq.(4.5), we obtain

(4.6)

∞

𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝐴𝐴 𝑅𝑅𝑅𝑅 �𝑒𝑒 𝑗𝑗 𝜔𝜔 𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 � 𝐽𝐽𝑛𝑛 (𝛽𝛽)𝑒𝑒 𝑗𝑗𝑗𝑗 𝜔𝜔 𝑚𝑚 𝑡𝑡 �

𝑛𝑛 =−∞

∞

Taking the real part yield

= 𝐴𝐴 𝑅𝑅𝑅𝑅 � � 𝐽𝐽𝑛𝑛 (𝛽𝛽)𝑒𝑒 𝑗𝑗 (𝜔𝜔 𝑐𝑐 +𝑛𝑛𝜔𝜔 𝑚𝑚 )𝑡𝑡 �

𝑛𝑛=−∞

∞

𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝐴𝐴 � 𝐽𝐽𝑛𝑛 (𝛽𝛽)𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐(𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 + 𝑛𝑛𝜔𝜔𝑚𝑚 )𝑡𝑡

𝑛𝑛=−∞

(4.7)

Fig.(4.1)

Dr. Ahmed A. Alrekaby

[4.5]

We observe that;

1. The spectrum consists of a carrier-frequency component plus an infinite number of

sideband components at frequencies ωc ± nωm (n = 1, 2, 3, ... ).

2. The relative amplitudes of the spectral lines depend on the value of Jn(β), and the

value of Jn(β) becomes very small for large values of n.

3. The number of significant spectral lines (that is, having appreciable relative

amplitude) is a function of the modulation index β. With β ≪ 1, only J0 and J1 are

significant, so the spectrum will consist of carrier and two sideband lines. But if

β ≫ 1, there will be many sideband lines. Figure (4.2) shows the amplitude spectra

of angle-modulated signals for several values of β.

Fig.(4.2)

Example 4.1: For the angle-modulated signal,

𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) = 10 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐 [2𝜋𝜋(106 )𝑡𝑡 + 10 𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠 2𝜋𝜋(103 )𝑡𝑡]

Find m(t) if;

(a) 𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) is a PM signal with 𝑘𝑘𝑝𝑝 = 10.

(b) 𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) is a FM signal with 𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓 = 10π.

Sol.

(a) 𝑘𝑘𝑝𝑝 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡) = 10 𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠 2𝜋𝜋(103 )𝑡𝑡

∴ 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡) = 𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠 2𝜋𝜋(103 )𝑡𝑡

𝑡𝑡

(b) 𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓 ∫−∞ 𝑚𝑚(𝜆𝜆) 𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑 = 10 𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠 2𝜋𝜋(103 )𝑡𝑡

𝑡𝑡

10

� 𝑚𝑚(𝜆𝜆) 𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑 =

𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠 2𝜋𝜋(103 )𝑡𝑡

10

π

−∞

𝑑𝑑 1

∴ 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡) = � sin 2𝜋𝜋(103 ) 𝑡𝑡� = 2(103 )𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐 2𝜋𝜋(103 )𝑡𝑡

U

U

U

𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑

π

Note that 𝜃𝜃(𝑡𝑡) = 𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 + 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡) = 2𝜋𝜋(106 )𝑡𝑡 + 10 𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠 2𝜋𝜋(103 )𝑡𝑡

Dr. Ahmed A. Alrekaby

[4.6]

and 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡) = 10 𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠 2𝜋𝜋(103 )𝑡𝑡

now 𝜙𝜙́(𝑡𝑡) = 20 (𝜋𝜋103 ) 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐 2𝜋𝜋(103 )𝑡𝑡

thus, the maximum phase deviation is

|𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)|𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚 = 10 𝑟𝑟𝑟𝑟𝑟𝑟

And the maximum frequency deviation is

Δ𝜔𝜔 = �𝜙𝜙́(𝑡𝑡)�𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚 = 20 (𝜋𝜋103 ) 𝑟𝑟𝑟𝑟𝑟𝑟/𝑠𝑠 = 10 𝐾𝐾𝐾𝐾𝐾𝐾

5. BANDWIDTH OF ANGLE MODULATED SIGNALS

5.1 Sinusoidal Modulation

The bandwidth of angle-modulated signal with sinusoidal modulation depends on

β and ωm. From mathematic relations;

U

U

∞

� 𝐽𝐽𝑛𝑛2 (𝛽𝛽) = 𝐽𝐽02 (𝛽𝛽) + 2(𝐽𝐽12 (𝛽𝛽) + 𝐽𝐽22 (𝛽𝛽) + ⋯ ) = 1

𝑛𝑛 =−∞

This property will help us to find the power of angle modulated signal as

2

2

2

𝑃𝑃 = �𝐴𝐴 𝐽𝐽0 (𝛽𝛽)⁄√2� + 2 ��𝐴𝐴 𝐽𝐽1 (𝛽𝛽)⁄√2� + �𝐴𝐴 𝐽𝐽2 (𝛽𝛽)⁄√2� + ⋯ �

𝐴𝐴2

𝐴𝐴2

𝐴𝐴2 2

[𝐽𝐽0 (𝛽𝛽) + 2(𝐽𝐽12 (𝛽𝛽) + 𝐽𝐽22 (𝛽𝛽) + ⋯ )] =

×1=

=

2

2

2

Now we can define the bandwidth of angle modulated signal as the band of

frequencies or harmonics which consists about of 98% of the normalized total

signal power and is given by;

𝑊𝑊𝐵𝐵 ≈ 2(𝛽𝛽 + 1)𝜔𝜔𝑚𝑚

(5.1)

When β ≪ 1, the signal is an NB angle-modulated signal and its bandwidth is

approximately equal 2ωm. Usually a value of β < 0.2 is taken to be sufficient to

satisfy this condition.

Let us consider β =1, then 𝐽𝐽0 (1) = 0.7652, 𝐽𝐽1 (1) = 0.44, 𝐽𝐽2 (1) = 0.1149,

𝐽𝐽3 (1) = 0.002477, then the power considered in the terms of n = 0,1, and 2

1

𝑃𝑃 = �𝐽𝐽0 2 (1) + 2 �𝐽𝐽1 2 (1) + 𝐽𝐽2 2 (1)��

2

1

= [0.76522 + 2(0.442 + 0.11492 )] = 0.495

2

The sum of P for n=2 is 99% of the total power, which is 0.5. If the

amplitude 𝐽𝐽𝑛𝑛 (𝛽𝛽) < 0.1, it can be neglected.

5.2 Arbitrary Modulation:

For an angle-modulated signal with an arbitrary modulating signal m(t) bandlimited to ωM rad/s, we define the deviation ratio D as

𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚 𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓 𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑 ∆𝜔𝜔

=

(5.2)

𝐷𝐷 =

𝜔𝜔𝑀𝑀

𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏𝑏ℎ 𝑜𝑜𝑜𝑜 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡)

The deviation ratio D plays the same role for arbitrary modulation as the

modulation index β plays for sinusoidal modulation. Replacing β by D and ωm by

ωM in Eq. (5.1), we have

𝑊𝑊𝐵𝐵 ≈ 2(𝐷𝐷 + 1)𝜔𝜔𝑀𝑀 ≈ 2(∆𝜔𝜔 + 𝜔𝜔𝑀𝑀 )

(5.3)

U

Dr. Ahmed A. Alrekaby

[4.7]

This expression for bandwidth is generally referred to as Carson's rule. If 𝐷𝐷 ≪ 1, the

bandwidth is approximately 2 ωM ,and the signal is known as a narrowband (NB)

angle-modulated signal. If 𝐷𝐷 ≫ 1, the bandwidth is approximately 2DωM = 2∆ω,

which is twice the peak frequency deviation. Such a signal is called a wideband (WB)

angle-modulated signal.

Example 5.1:

(a) Estimate BFM and BPM for the modulating signal m(t) for kf = 2π×105 and kp = 5π .

(b) Repeat the problem if the amplitude of m(t) is doubled.

U

Sol.

(a) The peak amplitude of m(t) is unity. Hence, 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡)|𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚 = 1. We now determine the

essential bandwidth B of m(t). The Fourier series for this periodic signal is given by

2𝜋𝜋

𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡) = � 𝑎𝑎𝑛𝑛 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐 𝑛𝑛𝜔𝜔𝑜𝑜 𝑡𝑡

𝜔𝜔𝑜𝑜 =

= 104 𝜋𝜋

2 × 10−4

U

𝑛𝑛

Where

−8

𝑎𝑎𝑛𝑛 = � 𝜋𝜋 2 𝑛𝑛2 𝑛𝑛 𝑜𝑜𝑜𝑜𝑜𝑜

0

𝑛𝑛 𝑒𝑒𝑒𝑒𝑒𝑒𝑒𝑒

It can be seen that the harmonic amplitudes decrease rapidly with n. The third and

fifth harmonic powers are 1.21 and 0.16%, respectively, of the fundamental

component power. Hence, we are justified in assuming the essential bandwidth of

m(t) as the frequency of the third harmonic, that is, 3(104/2) Hz. Thus,

fM =15 kHz

For FM:

1

1

∆𝜔𝜔

=

𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡)|𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚 =

(2π × 105 ) × 1 = 100 𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘

∆𝑓𝑓 =

2𝜋𝜋

2𝜋𝜋 2𝜋𝜋

and

𝐵𝐵𝐹𝐹𝐹𝐹 = 2(∆𝑓𝑓 + 𝑓𝑓𝑀𝑀 ) = 230 𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘

The deviation ratio D is given by

∆𝑓𝑓 100

=

𝐷𝐷 =

15

𝑓𝑓𝑀𝑀

4

For PM: the peak amplitude of 𝑚𝑚́(𝑡𝑡) is 2×10 and

1

𝑘𝑘 𝑚𝑚́(𝑡𝑡)|𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚 = 50 𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘

∆𝑓𝑓 =

2𝜋𝜋 𝑝𝑝

Hence,

𝐵𝐵𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑃 = 2(∆𝑓𝑓 + 𝑓𝑓𝑀𝑀 ) = 130 𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘

and

U

U

U

Dr. Ahmed A. Alrekaby

[4.8]

∆𝑓𝑓 50

=

𝑓𝑓𝑀𝑀 15

(b) Doubling m(t) doubles its peak value. Hence, 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡)|𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚 =2. But its bandwidth is

unchanged (𝑓𝑓𝑀𝑀 = 15 𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘).

For FM:

1

1

∆𝑓𝑓 =

𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡)|𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚 =

(2π × 105 ) × 2 = 200 𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘

2𝜋𝜋

2𝜋𝜋

and

𝐵𝐵𝐹𝐹𝐹𝐹 = 2(∆𝑓𝑓 + 𝑓𝑓𝑀𝑀 ) = 430 𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘

The deviation ratio D is given by

∆𝑓𝑓 200

=

𝐷𝐷 =

15

𝑓𝑓𝑀𝑀

For PM: Doubling m(t) doubles its derivative so that now 𝑚𝑚́(𝑡𝑡)|𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚 = 4×104 , and

1

𝑘𝑘 𝑚𝑚́(𝑡𝑡)|𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚 = 100𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘

∆𝑓𝑓 =

2𝜋𝜋 𝑝𝑝

Hence,

𝐵𝐵𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑃 = 2(∆𝑓𝑓 + 𝑓𝑓𝑀𝑀 ) = 230 𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘

and

∆𝑓𝑓 100

=

𝐷𝐷 =

15

𝑓𝑓𝑀𝑀

Observe that doubling the signal amplitude roughly doubles the bandwidth of both

FM and PM waveforms.

𝐷𝐷 =

U

U

U

If m(t) is time-expanded by a factor of 2; that is, if the period of m(t) is 4×10-4 ,then

the signal spectral width (bandwidth) reduces by a factor of 2. We can verify this by

observing that the fundamental frequency is now 2.5 kHz, and its third harmonic is

7.5 kHz. Hence, fM = 7.5 kHz, which is half the previous bandwidth. Moreover, time

expansion does not affect the peak amplitude so that 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡)|𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚 = 1. However,

𝑚𝑚́(𝑡𝑡)|𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚 is halved, that is, 𝑚𝑚́(𝑡𝑡)|𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚 = 10, 000.

For FM:

1

∆𝑓𝑓 =

𝑘𝑘 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡)|𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚 = 100 𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘

2𝜋𝜋 𝑓𝑓

and

𝐵𝐵𝐹𝐹𝐹𝐹 = 2(∆𝑓𝑓 + 𝑓𝑓𝑀𝑀 ) = 2(100 + 7.5) = 215 𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘

U

For PM:

U

Hence,

∆𝑓𝑓 =

1

𝑘𝑘 𝑚𝑚́(𝑡𝑡)|𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚 = 25 𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘

2𝜋𝜋 𝑝𝑝

𝐵𝐵𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑃 = 2(∆𝑓𝑓 + 𝑓𝑓𝑀𝑀 ) = 65 𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘

Dr. Ahmed A. Alrekaby

[4.9]

Note that time expansion of 𝒎𝒎(𝒕𝒕) has very little effect on the FM band width, but it

halves the PM bandwidth. This verifies that the PM spectrum is strongly dependent

on the spectrum of 𝒎𝒎(𝒕𝒕).

6. GENERATION OF ANGLE-MODULUED SIGNALS

6.1 Narrowband Angle-Modulated Signals:

The generation of narrowband angle-modulated signals is easily accomplished in

view of Eq.(3.2) and (3.3). This is illustrated in Fig.(6.1)

U

U

xNBPM(t)

A sinωct

A cosωct

xNBFM(t)

A sinωct

A cosωct

Fig.(6.1)

6.2 Wideband Angle-Modulated Signals:

There are two methods of generating wideband (WB) angle-modulated signals; the

indirect method and the direct method.

U

6.2.1 Indirect Method of Armstrong

In this method, an NB angle-modulated signal is produced first and then converted to

a WB angle-modulated signal by using frequency multipliers. The frequency

multiplier multiplies the argument of the input sinusoid by n. Thus, if the input of a

frequency multiplier is

𝑥𝑥(𝑡𝑡) = 𝐴𝐴 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐[𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 + 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)]

Then the output of the frequency multiplier is

𝑦𝑦(𝑡𝑡) = 𝐴𝐴 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐[𝑛𝑛𝑛𝑛𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 + 𝑛𝑛𝑛𝑛(𝑡𝑡)]

Use of frequency multiplication normally increases the carrier frequency to an

impractically high value. To avoid this, a frequency conversion (using a mixer or

DSB modulator) is necessary to shift the spectrum.

U

Dr. Ahmed A. Alrekaby

[4.10]

6.2.2 Direct Generation

In a voltage-controlled oscillator (VCO), the frequency is controlled by an external

voltage. The oscillation frequency varies linearly with the control voltage. We can

generate an FM wave by using the modulating signal m(t) as a control signal.

ωi(t) = ωc + kf m(t)

One can construct a VCO using variable reactive element (C or L) in resonant circuit

of an oscillator. In Hartley or Colpitt oscillators, the frequency of oscillation is given

by

1

𝜔𝜔𝑜𝑜 =

√𝐿𝐿𝐿𝐿

If the capacitance C is varied by the modulating signal m(t)

𝐶𝐶 = 𝐶𝐶𝑜𝑜 − 𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘(𝑡𝑡)

1

1

𝜔𝜔𝑜𝑜 =

=

⁄

𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘(𝑡𝑡)

𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘(𝑡𝑡) 1 2

�𝐿𝐿𝐶𝐶𝑜𝑜 �1 −

�

�𝐿𝐿𝐶𝐶𝑜𝑜 �1 − 𝐶𝐶 �

𝐶𝐶

U

𝑜𝑜

𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘(𝑡𝑡)

≈

�1 +

�

2𝐶𝐶𝑜𝑜

�𝐿𝐿𝐶𝐶𝑜𝑜

Where (1 + 𝑥𝑥)𝑛𝑛 ≈ 1 + 𝑛𝑛𝑛𝑛 𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓|𝑥𝑥| ≪ 1. Thus,

𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘(𝑡𝑡)

𝜔𝜔𝑜𝑜 = 𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 �1 +

�

2𝐶𝐶𝑜𝑜

1

𝑜𝑜

𝑘𝑘𝑘𝑘(𝑡𝑡)

≪1

𝐶𝐶𝑜𝑜

𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 =

1

�𝐿𝐿𝐶𝐶𝑜𝑜

𝑘𝑘𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐

𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓 =

𝜔𝜔𝑜𝑜 = 𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 + 𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡)

2𝐶𝐶𝑜𝑜

The main advantage of direct FM is that large frequency deviations are possible and

thus less frequency multiplication is required. The major disadvantage is that the

carrier frequency tends to drift and so additional circuitry is required for frequency

stabilization.

7. DEMODULATION OF ANGLE-MODULATED SIGNALS

Demodulation of an FM signal requires a system that produces an output proportional

to the instantaneous frequency deviation of the input signal. Such a system is called a

frequency discriminator. If the input to an ideal discriminator is an angle-modulated

signal

𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝐴𝐴 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐[𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 + 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)]

U

Dr. Ahmed A. Alrekaby

[4.11]

then the output of the discriminator is

𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑(𝑡𝑡)

𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑

where kd is the discriminator sensitivity. For FM

𝑦𝑦𝑑𝑑 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝑘𝑘𝑑𝑑 𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡)

The characteristics of an ideal frequency discriminator are shown below

𝑦𝑦𝑑𝑑 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝑘𝑘𝑑𝑑

The frequency discriminator also can be used to demodulate PM signals. For PM,

𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡) is given by

𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡) = 𝑘𝑘𝑝𝑝 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡)

Then 𝑦𝑦𝑑𝑑 (𝑡𝑡)

𝑑𝑑 𝑚𝑚(𝑡𝑡)

𝑦𝑦𝑑𝑑 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝑘𝑘𝑑𝑑 𝑘𝑘𝑝𝑝

𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑

Integration of the discriminator output yields a signal which is proportional to m(t). A

demodulator for PM can therefore be implemented as an FM demodulator followed

by an integrator. A simple approximation to the ideal discriminator is an idealdifferentiator followed by an envelope detector.

the output of the differentiator is

𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑(𝑡𝑡)

� 𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠[𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 + 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)]

𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑

The signal 𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐́ (𝑡𝑡) is both amplitude- and angle-modulated. The envelope of 𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐́ (𝑡𝑡)is

𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑(𝑡𝑡)

𝐴𝐴 �𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 +

�

𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑

The output of the envelop detector is

𝑦𝑦𝑑𝑑 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝜔𝜔𝑖𝑖

Which is the instantaneous frequency of the 𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡).

𝑥𝑥𝑐𝑐́ (𝑡𝑡) = −𝐴𝐴 �𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 +

Dr. Ahmed A. Alrekaby

[4.12]

8. NOISE IN ANGLE MODULATION SYSTEMS

The transmitted signal 𝑋𝑋𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) has the form

𝑋𝑋𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐[𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 + 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)]

Where

𝑘𝑘𝑝𝑝 𝑋𝑋(𝑡𝑡)

𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓 𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑃

U

𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡) = �

𝑡𝑡

𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓 � 𝑋𝑋(𝜆𝜆) 𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑

−∞

(8.1)

(8.2)

𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓 𝐹𝐹𝐹𝐹

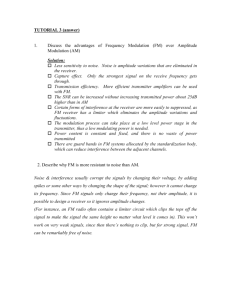

Figure (8.1) shows a model for the angle demodulation system. The predetection

filter bandwidth 𝐵𝐵𝑇𝑇 = 2(𝐷𝐷 + 1)𝐵𝐵. The detector input is

𝑌𝑌𝑖𝑖 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝑋𝑋𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) + 𝑛𝑛𝑖𝑖 (𝑡𝑡)

Fig.(8.1)

Where

𝑛𝑛𝑖𝑖 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝑛𝑛𝑐𝑐 (𝑡𝑡) 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐ω𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡− 𝑛𝑛𝑠𝑠 (𝑡𝑡) 𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠ω𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡

= 𝑣𝑣𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡) 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐[𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 + 𝜙𝜙𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡)]

The carrier amplitude remains constant, therefore

and

1

𝑆𝑆𝑖𝑖 = 𝐸𝐸[𝑋𝑋𝑐𝑐2 (𝑡𝑡)] = 𝐴𝐴2𝑐𝑐

2

𝑁𝑁𝑖𝑖 = 𝜂𝜂𝐵𝐵𝑇𝑇

Hence,

𝐴𝐴2𝑐𝑐

𝑆𝑆

(8.3)

� � =

𝑁𝑁 𝑖𝑖 2𝜂𝜂𝐵𝐵𝑇𝑇

𝑆𝑆

Which is independent of 𝑋𝑋(𝑡𝑡). � � is often called the carrier-to-noise ratio (CNR).

𝑁𝑁

𝑖𝑖

𝑌𝑌𝑖𝑖 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝑉𝑉(𝑡𝑡) 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐 [𝜔𝜔𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 + 𝜃𝜃(𝑡𝑡)]

Where

𝑉𝑉(𝑡𝑡) = {[𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐 + 𝑣𝑣𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡)𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝜙𝜙𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡)]2 + [𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐 𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠 + 𝑣𝑣𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡)𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝜙𝜙𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡)]2 }1/2

and

𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐 𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠(𝑡𝑡) + 𝑣𝑣𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡)𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝜙𝜙𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡)

𝜃𝜃(𝑡𝑡) = 𝑡𝑡𝑡𝑡𝑡𝑡−1

𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐(𝑡𝑡) + 𝑣𝑣𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡)𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝜙𝜙𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡)

(8.4)

(8.5)

(8.6)

The limiter suppresses any amplitude variation 𝑉𝑉(𝑡𝑡). Hence, in angle modulation,

SNRs are derived from consideration of 𝜃𝜃(𝑡𝑡) only. The detector is assumed to be

ideal. The output of the detector is

𝜃𝜃(𝑡𝑡)

𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓 𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑃

(8.7)

𝑌𝑌𝑜𝑜 (𝑡𝑡) = �𝑑𝑑 𝜃𝜃(𝑡𝑡)

𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓 𝐹𝐹𝐹𝐹

𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑

Let

Dr. Ahmed A. Alrekaby

[4.13]

where

𝑌𝑌𝑖𝑖 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝑅𝑅𝑅𝑅�𝑌𝑌(𝑡𝑡)𝑒𝑒 𝑗𝑗 𝜔𝜔 𝑐𝑐 𝑡𝑡 �

𝑌𝑌(𝑡𝑡) = 𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐 𝑒𝑒 𝑗𝑗 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡) + 𝑣𝑣𝑛𝑛 𝑒𝑒 𝑗𝑗 𝜙𝜙 𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡)

(8.8)

(8.9)

For signal dominance case, 𝑣𝑣𝑛𝑛 ≪ 𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐 for almost all t. from Fig.(8.2) the length L of

arc AB is

𝐿𝐿 = 𝑌𝑌(𝑡𝑡)[𝜃𝜃(𝑡𝑡) − 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)]

(8.10)

Fig.(8.2)

and

𝑌𝑌(𝑡𝑡) = 𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐 + 𝑣𝑣𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡) 𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐𝑐[𝜙𝜙𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡) − 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)] ≈ 𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐

𝐿𝐿 ≈ 𝑣𝑣𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡) 𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠[𝜙𝜙𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡) − 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)]

Hence, from Eq.(8.10), we obtain

𝑣𝑣𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡)

𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠[𝜙𝜙𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡) − 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡)]

𝜃𝜃(𝑡𝑡) ≈ 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡) +

𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐

Replacing 𝜙𝜙𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡) − 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡) with 𝜙𝜙𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡) will not affect the result. Thus

𝑣𝑣𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡)

𝜃𝜃(𝑡𝑡) ≈ 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡) +

𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠𝑠[𝜙𝜙𝑛𝑛 (𝑡𝑡)]

𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐

𝑛𝑛𝑠𝑠 (𝑡𝑡)

𝜃𝜃(𝑡𝑡) ≈ 𝜙𝜙(𝑡𝑡) +

𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐

From Eqs.(8.7) and (8.2) the detector output is

𝑛𝑛𝑠𝑠 (𝑡𝑡)

𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓 𝑃𝑃𝑃𝑃

𝑌𝑌𝑜𝑜 (𝑡𝑡) = 𝜃𝜃(𝑡𝑡) = 𝑘𝑘𝑝𝑝 𝑋𝑋(𝑡𝑡) +

𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐

𝑑𝑑 𝜃𝜃(𝑡𝑡)

𝑛𝑛́ 𝑠𝑠 (𝑡𝑡)

= 𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓 𝑋𝑋(𝑡𝑡) +

𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓 𝐹𝐹𝐹𝐹

𝑌𝑌𝑜𝑜 (𝑡𝑡) =

𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑

𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐

8.1 (S/N)o in PM systems

From Eq.(8.15)

𝑆𝑆𝑜𝑜 = 𝐸𝐸�𝑘𝑘𝑝𝑝2 𝑋𝑋 2 (𝑡𝑡)� = 𝑘𝑘𝑝𝑝2 𝐸𝐸[𝑋𝑋 2 (𝑡𝑡)] = 𝑘𝑘𝑝𝑝2 𝑆𝑆𝑋𝑋

1

1

1

𝑁𝑁𝑜𝑜 = 𝐸𝐸 � 2 𝑛𝑛𝑠𝑠2 (𝑡𝑡)� = 2 𝐸𝐸[𝑛𝑛𝑠𝑠2 (𝑡𝑡)] = 2 (2𝜂𝜂𝜂𝜂)

𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐

𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐

𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐

U

Hence,

(8.11)

(8.12)

(8.13)

(8.14)

(8.15)

(8.16)

(8.17)

(8.18)

Dr. Ahmed A. Alrekaby

[4.14]

𝑘𝑘𝑝𝑝2 𝐴𝐴2𝑐𝑐 𝑆𝑆𝑋𝑋

𝑆𝑆

� � =

𝑁𝑁 𝑜𝑜

2𝜂𝜂𝜂𝜂

Since,

Eq.(8.19) can be expressed as

(8.19)

𝐴𝐴2𝑐𝑐

𝑆𝑆𝑖𝑖

=

𝛾𝛾 =

𝜂𝜂𝜂𝜂 2𝜂𝜂𝜂𝜂

(8.20)

𝑆𝑆

� � = 𝑘𝑘𝑝𝑝2 𝑆𝑆𝑋𝑋 𝛾𝛾

𝑁𝑁 𝑜𝑜

(8.21)

8.2 (S/N)o in FM systems

From Eq.(8.16)

𝑆𝑆𝑜𝑜 = 𝐸𝐸�𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓2 𝑋𝑋 2 (𝑡𝑡)� = 𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓2 𝐸𝐸[𝑋𝑋 2 (𝑡𝑡)] = 𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓2 𝑆𝑆𝑋𝑋

1

1

𝑁𝑁𝑜𝑜 = 𝐸𝐸 � 2 [𝑛𝑛́ 𝑠𝑠 (𝑡𝑡)]2 � = 2 𝐸𝐸[[𝑛𝑛́ 𝑠𝑠 (𝑡𝑡)]2 ]

𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐

𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐

U

The PSD of 𝑛𝑛́ 𝑠𝑠 (𝑡𝑡) is given by

Then

2

𝑆𝑆𝑛𝑛 𝑠𝑠́ 𝑛𝑛́ 𝑠𝑠 (𝜔𝜔) = 𝜔𝜔2 𝑆𝑆𝑛𝑛 𝑠𝑠 𝑛𝑛 𝑠𝑠 (𝜔𝜔) = �𝜔𝜔 𝜂𝜂

0

(8.22)

(8.23)

𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓𝑓 |𝜔𝜔| < 𝑊𝑊 (= 2𝜋𝜋𝜋𝜋)

𝑜𝑜𝑜𝑜ℎ𝑒𝑒𝑒𝑒𝑒𝑒𝑒𝑒𝑒𝑒𝑒𝑒

1 1 𝑊𝑊 2

2 𝜂𝜂 𝑊𝑊 3

� 𝜔𝜔 𝜂𝜂 𝑑𝑑𝑑𝑑 =

𝑁𝑁𝑜𝑜 = 2

𝐴𝐴𝑐𝑐 2𝜋𝜋 −𝑊𝑊

3 𝐴𝐴2𝑐𝑐 2𝜋𝜋

Hence,

3𝐴𝐴2𝑐𝑐 (2𝜋𝜋)𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓2 𝑆𝑆𝑋𝑋

𝑆𝑆

� � =

𝑁𝑁 𝑜𝑜

2𝜂𝜂𝑊𝑊 3

Using Eq.(8.20), we can express Eq.(8.26) as

𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓2 𝑆𝑆𝑋𝑋

𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓2 𝑆𝑆𝑋𝑋

𝑆𝑆

𝐴𝐴2𝑐𝑐

� � = 3� 2 ��

� = 3 � 2 � 𝛾𝛾

𝑁𝑁 𝑜𝑜

𝑊𝑊

2𝜂𝜂𝜂𝜂

𝑊𝑊

Since Δ𝜔𝜔 = �𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓 𝑋𝑋(𝑡𝑡)�

= 𝑘𝑘𝑓𝑓 [|𝑋𝑋(𝑡𝑡)| ≤ 1], Eq.(8.27) can be rewritten as

𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚𝑚

(8.24)

(8.25)

(8.26)

(8.27)

𝑆𝑆

Δ𝜔𝜔 2

(8.28)

� � = 3 � � 𝑆𝑆𝑋𝑋 𝛾𝛾 = 3𝐷𝐷2 𝑆𝑆𝑋𝑋 𝛾𝛾

𝑁𝑁 𝑜𝑜

𝑊𝑊

Equation (8.25) indicates that the output noise power is inversely proportional to the

𝐴𝐴2

mean carrier power � 𝑐𝑐 � in FM. This effect is called noise quieting.

2

U

U

Example 8.1: consider an FM broadcast system with parameter ∆f=75 kHz and B=15

kHz. Assuming 𝑆𝑆𝑋𝑋 = 12, find the output SNR and calculate the improvement (in dB)

over the baseband system.

Sol.

Substituting the given parameters into Eq.(8.28), we obtain

2

1

𝑆𝑆

75(103 )

�

�

� 𝛾𝛾 = 37.5𝛾𝛾

� � = 3�

15(103 )

2

𝑁𝑁 𝑜𝑜

Now, 10 log 37.5=15.7 dB, which indicates that (𝑆𝑆/𝑁𝑁)𝑜𝑜 is about 16 dB better than

the baseband system.

U

U

U

Dr. Ahmed A. Alrekaby