An Exploration of Teacher Constructs Through a Rational-Emotive Behaviour Therapy... Dr Caroline Robertson, University College London 5 4

advertisement

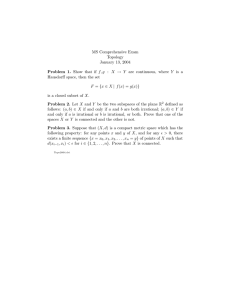

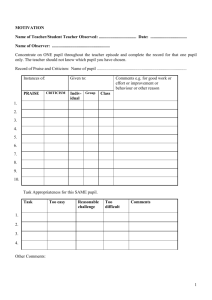

An Exploration of Teacher Constructs Through a Rational-Emotive Behaviour Therapy Framework Dr Caroline Robertson, University College London (robertson_c_j@hotmail.com) Aim To examine the relationship between teachers’ beliefs about work in schools, feelings of self-efficacy, reports of stress, feedback offered to pupils in class, and the impact of these on pupil behaviour. Background Current national agendas place emphasis on promoting the mental health and wellbeing of young people; however, it is questionable whether teachers will be able to support pupil wellbeing if their own emotional and social needs are not met (Weare & Grey, 2003). This study examined the variables that might be considered to contribute to teacher wellbeing, using the psychological framework of Rational-Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT). REBT interventions have been used with teachers to address negative or irrational thoughts/beliefs and the associated emotions and behaviours. It is hoped that teachers will then be more likely to remain in control, feel empowered and avoid levels of stress that accompany chronic states of exhaustion or ‘burnout’ (Maag, 2008). Methods Fifty-eight teachers from five secondary schools in a large Outer London Local Authority completed the following questionnaires: • Teacher Irrational Belief Scale (Bernard, 1990) • Teachers’ Sense of Efficacy Scale - Short Form (TschannenMoran & Woolfolk-Hoy, 2001) • Teacher Stress Questionnaire (Borg & Riding, 1993) In addition, the Observing Pupils and Teachers in Classrooms schedule (OPTIC; Merrett & Wheldall, 1986) was completed by an independent researcher, who rated both verbal teacher feedback and on-task pupil behaviour during one lesson for each teacher. Results The outcomes of the correlational analysis of the five variables are shown in Table 1. Table 1. Correlations of the Major Study Variables Variable 1 2 3 4 5 1. Irrational Beliefs Significant findings: 1. Stress positively correlated with irrational beliefs, but negatively correlated with self-efficacy. 2. Self-efficacy negatively correlated with irrational beliefs, but positively correlated with on-task pupil behaviour. 3. Positive teacher feedback positively X correlated with on-task pupil behaviour 2. Self-Efficacy - .36** 3. Stress .64*** - .42*** 4. On-Task Pupil Behaviour (%) - .06 .40** - .10 5. Positive Teacher Feedback (%) - .23 .19 - .21 .53*** Note. Whole scale scores used for Irrational Beliefs, Self-Efficacy & Stress measures. “Positive Teacher Feedback” = [(Positive Academic & Social Comments)/ (Positive & Negative, Academic & Social Comments)] x 100 *p < .05. ; ** p < .01 ; *** p < .001. Discussion 1. Stress: although direction of causality cannot be established through correlation, previous research using a structural equation modelling approach has suggested that low self-efficacy precedes job stress and subsequent burnout (Schwarzer & Hallum, 2008). Positive relationships between irrational beliefs and stress have previously been demonstrated by Bernard (1990). 2. Self-Efficacy: Tschannen-Moran, Woolfolk-Hoy and Hoy (1998) state that teachers weigh self-perceptions of personal teaching competence against the assumed requirements of the teaching task when assessing self-efficacy. The findings suggest that irrational beliefs are likely to impact on both elements of this assessment. Self-efficacy has previously been linked with pupil achievement and motivation (e.g. Ross, 1992), but not with on-task pupil behaviour. 3. Positive Teacher Feedback: the above findings support existing research relating positive pupil behaviour to teacher rates of approval in the classroom (e.g. Wheldall, Houghton & Merrett, 1989). Implications •To support the wellbeing of teachers (in terms of feelings of stress), it appears important to target any existing irrational beliefs and to bolster feelings of self-efficacy. •To support the wellbeing of pupils (in terms of their behaviour), it appears important to target the amount of positive feedback they receive from teachers in the classroom and the feelings of self-efficacy of their teachers. •The researcher found that a series of four one-hour INSET sessions based on REBT principles was not able to improve teachers’ ratings of these five variables in comparison with a no-intervention control group. Thus, it remains to be seen what form of intervention would best support positive change in these constructs for secondary school teaching staff. References Bernard, M. E. (1990). Taking the Stress out of Teaching. North Blackburn, VIC: Collins-Dove. Borg, M. G., & Riding, R. J. (1993). Teacher Stress and Cognitive Style. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 63, 271-286. Maag, J. (2008). Rational-Emotive Therapy to Help Teachers Control Their Emotions and Behavior when Dealing with Disagreeable Students. Intervention in School and Clinic, 44, 52-57. Merrett, F., & Wheldall, K. (1986). Observing Pupils and Teachers in Classrooms: A Behavioural Observations Schedule for Use in Schools. Educational Psychology, 6, 57-70. Ross, J. A. (1992). Teacher Efficacy and the Effect of Coaching on Student Achievement. Canadian Journal of Education, 17, 51–65. Schwarzer, R., & Hallum, S. (2008). Perceived Teacher Self-Efficacy as a Predictor of Job Stress and Burnout: Mediation Analyses. Applied Psychology, 57, 152-171. Tschannen-Moran, M., & Woolfolk-Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher Efficacy: Capturing an Elusive Construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 783-805. Tschannen-Moran, M., Woolfolk-Hoy, A., & Hoy, W. (1998). Teacher Efficacy: Its Meaning and Measure. Review of Educational Research, 68, 202-248. Wheldall, K., Houghton, S., & Merrett, F. (1989). Natural Rates of Teacher Approval and Disapproval in British Secondary School Classrooms. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 59, 38-48. Weare, K., & Gray, G. (2003). What Works in Developing Children’s Emotional and Social Competence and Wellbeing? DfES Research Report No. 456. Nottingham: DfES Publications