L R H

advertisement

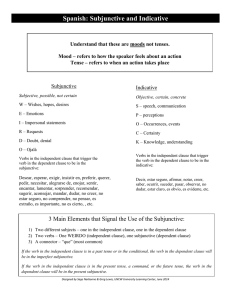

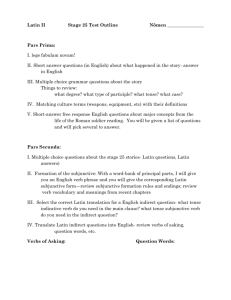

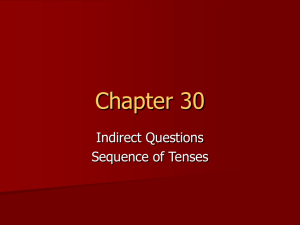

LATIN FOR RESEARCH IN THE HUMANITIES SEMINAR 17 ORATIO OBLIQUA In Latin, a speech or a narrative can either be recorded directly in the speaker’s own words, or it can be reported indirectly as the object of a verb. A speech or a narrative that is reported indirectly is an example of the oratio obliqua. The oratio obliqua follows its own distinct rules, some of which will come as no surprise given previous seminars. The particular nature and demands of the oratio obliqua can be understood by contrasting the following extract from an imaginary speech in English: Original words: Reported form: ‘… I have brought one cake for myself, and seven for the others. Don’t you think this is fair? I will do the same thing tomorrow...’ [He said that]… He had brought one cake for himself, and seven for the others. Did they not think that was fair? He would do the same thing the next day... Notice that in making the transition from the original speech to the reported form, several changes have taken place: (i) the personal pronouns have changed – I > he, myself > himself, you > they; (ii) the tenses of the finite verbs have changed – I have brought > he had brought; (iii) the adverb of time has changed – tomorrow > the next day. These sorts of changes also occur in Latin when we make the transition from direct speech to the oratio obliqua. (1) The verb of ‘saying’ Since the oratio obliqua is a form of reported speech or narrative, it is often – but not always – preceded by a verb of ‘saying’. There are, however, two points which it is important to bear in mind: • • The verb of ‘saying’ is often omitted, leaving only the ‘reported’ element. We need to understand the verb of ‘saying’ when translating. The verbs inquam and inquit never introduce the oratio obliqua: these verbs only ever introduce direct speech. (2) Simple and principal sentences Simple and principal sentences are transferred into the oratio obliqua in a manner depending on their type: (a) Statements, exclamations and rhetorical questions (i.e. where no answer is expected) are expressed by an acc + inf. DIRECT STATEMENT Romulus urbem condidit. Romulus founded the city. ORATIO OBLIQUA (INDIRECT) (Narrant:) Romulum urbem condidisse. 1 Cur ego pro hominibus ignavis sanguinem profudi? Why have I shed my blood for cowards? Cur se pro hominibus ignavis sanguinem profudisse? Why did he shed his blood for cowards? (b) Commands, prohibitions, wishes, and real questions (i.e. where an answer is expected) are expressed using the subjunctive: Ite, inquit, create consules ex plebe. Go and elect consuls from among the plebs. (Hortatus est:) irent, crearent consules ex plebe. Quis agis? What are you doing? …quis ageret. …what he was doing. (3) Subordinate clauses Subordinate clauses in the oratio obliqua are formed depending on their nature. (a) Indirect statements, commands, wishes, and questions – which are ordinarily formed using either an acc. + inf. or a subjunctive construction – retain their usual form in the oratio obliqua. Ego promitto me officium meum praestaturum esse. I promise that I shall do my duty. (Dixit:) se promittere se officium suum praestaturum esse. (He said that:) He promised to do his duty. In this example, note that the reported statement in the direct speech is expressed using an acc. + inf. In the oratio obliqua, the reported statement is again expressed using an acc. + inf. even though it itself follows an acc. + inf. (b) Clauses introduced by quod + indicative take the subjunctive in the oratio obliqua. Hoc praestamus maxime feris quod loquimur. We excel beasts most in this respect, that we speak. (Dixit:) hoc praestare maxime feris quod loquerentur. (c) Causal, consecutive, concessive, result, purpose, cum, dum, and relative clauses all take the subjunctive in the oratio obliqua. Maiorum quibus orti estis reminiscimini. Remember the ancestors from whom you are sprung. (Dixit:) maiorum quibus orti essent reminiscerentur. (4) Pronouns and adverbs When the verb of ‘saying’ (stated or implied) is in the third person, personal pronouns and possessive adjectives change in the following way: ego, me, nos meus, noster > > se suus tu, vos tuus, vester > > ille, illi illius, illorum 2 Naturally, pronouns like ‘this’ and adverbs of place like ‘here’ have to change to accommodate the distinction between the original, direct statement, and the reported oratio obliqua. In English, this > that, and here > there; so too in Latin. hic hic (here) huc hinc > > > > ille ibi eo inde iste istic istuc istinc > > > > ille illic illuc illinc Adverbs of time must also change where the verb of ‘saying’ is in the past tense, or may be assumed to be so: nunc hodie > > tunc eo die heri cras > > pridie postridie (5) Tenses The rules governing the use of tenses in the oratio obliqua are exceptionally clear, although it is only to be expected that it should be necessary to distinguish between the rules for infinitives (in acc. + inf. constructions) and those for finite verbs (in all other constructions). (a) Infinitives Dico I say Dixi I said eum amare that he is loving amavisse has loved amaturum esse will love copias mitti that forces are being sent missas esse have been sent missum iri will be sent eum amare that he was loving amavisse had loved amaturum esse would love copias mitti that forces were being sent missas esse had been sent missum iri would be sent (b) Finite verbs The tenses of the subjunctive follows the sequence of tenses and hence it is necessary to bear in mind the tense of the verb of ‘saying’, whether stated explicitly or understood from context. Hence, where the verb of ‘saying’ is in the present (primary sequence), the subjunctive will be either present or perfect; and where the verb of ‘saying’ is in the past (historic sequence), the subjunctive will be either imperfect or pluperfect. (6) Virtual oratio obliqua Sometimes, a verb of saying is implied, but the writer does not wish to comment on the truth or untruth of what he is effectively quoting, or wishes to leave the truthfulness of the indirect ‘quotation’ open to question. In this case, the verb of such clauses is subjunctive (cf. quod or quia + subjunctive; seminar 16). Paetus libros quos pater suus reliquisset mihi donavit. CICERO Paetus gave me the books which (as he said) his father had left. 3 Laudat Africanum Panaetius quod fuerit abstinens. CICERO Panaetius praises Africanus because (as he says) he was temperate. [N.B. This is an example of a virtually sub-oblique causal clause] (7) Conditional statements In Latin, there are three types of conditional statements, which are transferred into the oratio obliqua in different ways: Type 1 Indicative Conditions: condition true, consequence true Direct speech: condition (‘si’ clause) = indicative consequence (main clause) = indicative condition (‘si’ clause) = subjunctive consequence (main clause) = acc. + inf. Reported: Type 2 Subjunctive Conditions: potential condition Direct speech: e.g. Reported: e.g. Type 3 condition (‘si’ clause) = present/perfect subjunctive consequence (main clause) = present/perfect subj. Si peccet, doleat. condition (‘si’ clause) = follows sequence of tenses consequence (main clause) = acc. + future inf. (Dixit:) illum, si peccaret, doliturum esse. Subjunctive Conditions: impossible condition Direct speech: e.g. Reported: e.g. condition (‘si’ clause) = imperf/pluperf. subj. consequence (main clause) = imperf/pluperf. subj. Si peccavisset, doluisset. condition (‘si’ clause) = imperf/pluperf. subj. consequence = acc + future part. + fuisse* (Dixit:) illum, si peccavisset, doliturum fuisse. Note that type 2 and type 3 conditionals often feature a main clause which involves a verb in the indicative, whether to describe an action actually started or intended, or to indicate duty or possibility. This makes comparatively little difference to the oratio obliqua, as will be immediately apparent: our primary concern is with the condition. (8) Subjunctive by attraction Sometimes we will encounter a subjunctive verb in the oratio obliqua when we would ordinarily expect to see an indicative. The subjunctive is used in such cases because the clause is dependent on another subjunctive or infinitive: what would ordinarily be indicative is ‘attracted’ to the subjunctive mood because of its surroundings. Nescire quid antequam natus sis acciderit, id est semper esse CICERO puerum. Not to know what happened before you were born, that is to be a child always. * If the verb lacks a future participle or is passive, futurum fuisse + ut + imperfect subjunctive is used. 4 Exercises (1) Oratio recta Oratio obliqua ‘…Ipse vos incolumes huc duxi: none consilium meum bonum putatis? Proinde nolite cunctari; mihi parete; cras victoriam habebimus. Num hostes superiores sunt?’ Se ipsum illos incolumes eo duxisse: nonne consilium suum bonum putarent? Proinde ne cunctarentur; sibi parerent; postridie victoriam se habituros. Num hostes superiores esse? incolumis (adj) proinde cunctor, -ari pareo, -ere unharmed, safe onward from this point, consequently, accordingly to hang back, hesitate, be reluctant, delay to appear, be evident, to present (oneself), to obey (2) Ad haec Caesar respondit: se civitatem conservaturum, si, prius quam murum aries attigisset, se dedidissent. aries, -ietis attingo, -tingere, -tigi, -tactum battering ram to come into contact, to touch, to assault (3) Ei legationi Arisovistus respondit: si quid ipsi a Caesare opus esset, sese ad eum venturum fuisse. (4) Hoc video, dum breviter voluerim dicere, dictum esse a me paullo obscurius. 5