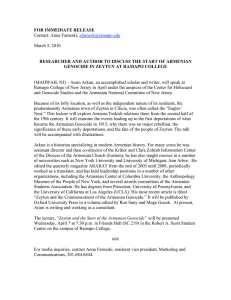

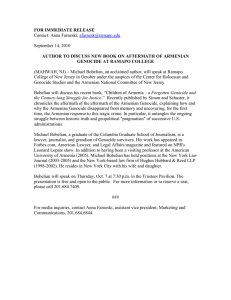

A Climate for Abduction, a Climate for Redemption: The

advertisement