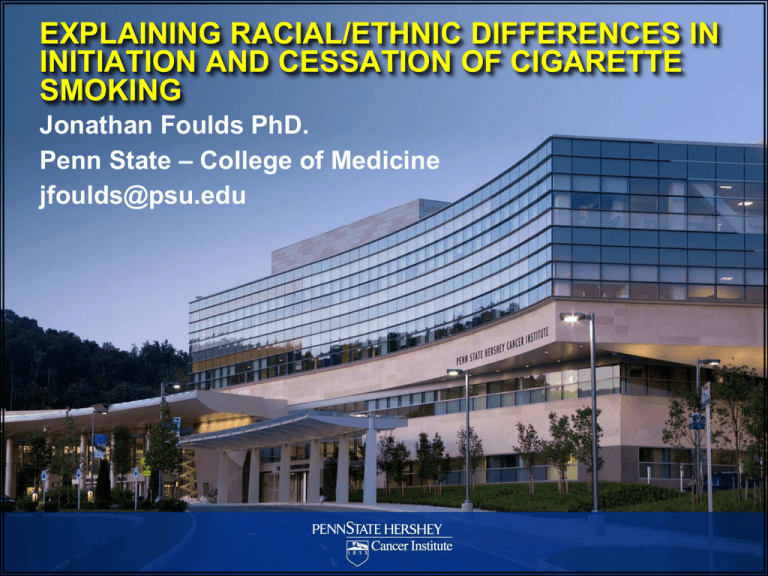

EXPLAINING RACIAL/ETHNIC DIFFERENCES IN INITIATION AND CESSATION OF CIGARETTE SMOKING

advertisement

EXPLAINING RACIAL/ETHNIC DIFFERENCES IN INITIATION AND CESSATION OF CIGARETTE SMOKING Jonathan Foulds PhD. Penn State – College of Medicine jfoulds@psu.edu We Are Penn State Acknowledgements and conflicts. Current and recent funding support mainly from Penn State College of Medicine, New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services, but also SRNT, Cancer Institute of New Jersey, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Rutgers CHF & others. Consulting/honoraria received from pharma. companies producing tobacco treatment meds (Pfizer, GSK, Novartis, Celtic Pharma & others). Compensated for testimony in litigation for plaintiffs against tobacco companies. Never received any funding from the tobacco industry Wrote a regular weblog for a health website at: www.healthline.com/blogs/smoking_cessation/ Volunteer as a “Health Expert” on the smoking cessation community on www.WebMD.com Thanks to numerous colleagues for sharing their slides. Global Tobacco Use More than 17 billion cigarettes are smoked every day, and that number is rising. Almost 1 billion men in the world smoke— about 35 percent of men in high-resource countries, and 50 percent of men in lowincome countries. Nearly 60 percent of Chinese men are smokers, and the country consumes more than 37 percent of the world’s cigarettes. Global Tobacco Use 2 About 250 million women in the world are daily smokers; 22 percent of women in high-resource countries and 9 percent of women in low- and middle-resource countries. Cigarettes account for the largest share of manufactured tobacco products (96 percent of total value sales), although in South Asia, bidi consumption exceeds cigarette consumption by an order of magnitude and use of oral tobacco remains a widespread problem. Global Tobacco Use 3 About 6.3 trillion cigarettes were produced in 2010— more than 900 cigarettes for every man, woman, and child on the planet. Source: The Tobacco Atlas, 2010. http://www.tobaccoatlas.org/ Smoking kills more people in the US than all of the following combined: AIDS Alcohol Motor vehicle injuries Fires Heroin Cocaine Homicide Suicide My main research interests 1. Finding better ways to help more smokers to quit and stay quit. 2. Trying to gain a better understanding of nicotine dependence and its assessment. 3. Assessing the potential impact of other (non-cig) nicotine delivery products re harm reduction. 1. Smoking Cessation About to start a randomized trial of motivational feedback and relapse prevention materials for smoking cessation in treatment-seeking smokers. Applied for a grant, along with Dr Legro (OBGYN) and others to evaluate a cell-text based cessation intervention for pregnant smokers. 6m triple combo vs standard duration patch in medical patients (Steinberg et al, 2009) 2. Understanding nicotine dependence Previously published laboratory studies showing: - Nicotine improves some aspects of cognitive performance and speeds up EEG alpha waves. - Smokers with schizophrenia absorb higher amounts of nicotine and CO than control smokers. Example: Understanding nicotine dependence (FTND & HSI) 3. Evaluating alternative nicotine products Previously published studies showing: - Snus use by Swedish men had a positive public health impact in that country. - More Swedish men are quitting smoking by switching to snus than via any other smoking cessation aid. Incidence rate for three types of cancer (by 2004) as a function of tobacco use status in male Swedish construction workers at recruitment (1978-92) Incidence per 100,000 person years 90 82.3 80 Current Smokers 70 Current Snusers 60 Never Tobacco Users 50 40 30 20 13 10 6 8.6 8.8 6.9 2.7 3.1 3.9 0 Lung Oral Cancer Type Pancreatic Basic E-cig. Anatomy THE CONTINUUM OF HARM FROM NICOTINE-DELIVERING PRODUCTS E-cig ? HARM 100% 10% 0% Current cigarette smoking: % of 12th-grade students who reported smoking any cigarettes in the past 30 days by race, 1977–2010 45 40 35 25 White Black Hispanic 20 15 10 5 0 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Percent 30 Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse, Monitoring the Future Survey What caused the dramatic reduction in smoking among AA youth, 1975-1992?...and why was the decline so much bigger than in white youth? By 1992 White students were almost 4 times more likely to have smoked in the past 30 days than were their AA counterparts. = Possible Explanations: Oredein &Foulds 2011 1. Differential reliability of self report? Not supported by cotinine studies 2. Differential school dropout? Partial support, but AA HS dropout rate began declining in ’88 and studies including dropouts still find difference. 3. AA students using other substances? No, it came down more in AA youth over study period. e.g. 1996-2000, any illicit use prevalence: w=43%, AA=33% Possible Explanations: Oredein &Foulds 2011 1. Stronger negative attitudes to smoking and closer parental supervision among AA parents? Supported by numerous studies plus differential increase in AA single mom households 1970-1990 (30-51%) as compared with W households (8% to 16%). 2. Differential price sensitivity 1979-89 40% real increase in cigarette price. AA youth more price sensitive. 1970 to 1990 massive increase in food stamps. By 1997 90% of AA children (37% W) lived at some time in family receiving food stamps. Possible Explanations: Oredein &Foulds 2011 A number of protective factors are present to a greater extent in the AA community but we could not find clear evidence that these increased more 1977-1992: These include increased sensitivity/awareness of antismoking health education, increased religious participation. Policy Implications: Probably the single most effective intervention to reduce youth smoking is to increase the real price…primarily via increases in state and federal excise taxes. This is one of the few tax increases consistently supported by the public. Trends in lung cancer death rates in 20- to 39-year-old non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black men and women (1992-2006). Jemal A et al. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:3349-3352 ©2009 by American Association for Cancer Research Percent % of high school students who smoked on at least 20 of the past 30 days in US localities by race, YRBS 2009 18 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 Black Hispanic White Total Philadelphia Seattle Boston San Diego Chicago 1.2 3.1 15.6 3.6 1.4 9.8 3.5 3.4 1.8 0.9 9.4 3.1 2.2 2.2 3.7 2.8 1 3.2 9.1 2.7 New York City 0.7 2.4 6.3 2.4 Data available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/tables/adult/table_6.htm Biochemical Measures of Smoke intake, Menthol vs non-menthol (n=125) (Williams et al,2008) *p<0.05, **p<0.01 Menthol NonMenthol Blood nicotine (ng/ml) 27.2** 22.4 Blood Cotinine (ng/ml) 294* 240 Exhaled CO 25.1* 20.7 What is the mechanism causing menthol cigarettes to be more addictive and carcinogenic? Its easier to inhale more nicotine and other toxins from a menthol cigarette in circumstances that require it (eg expensive cigarettes or limited smoking opportunities), because the increased menthol dose from increased puffing proportionately cools the smoke harshness. A menthol cigarette has more “elastic” or “compensatable” nicotine (and other toxin) delivery. % who quit Gundersen et al (2009). % of ever smokers (who have attempted to quit) who have quit in the 2005 NHIS by race/ethnicity Significantly lower quitting success among African Americans and Hispanics if they smoke menthols (but not whites). 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 63 62 62 44 61 49 menthol smokers non-menthol smokers W AA H Conclusion All other things being equal, menthol smokers are more dependent than non-menthol smokers, with the effect being larger at lower cigarette consumption (e.g. <10pd), and larger for those who are unemployed or living in relative poverty, particularly in an area with expensive cigarettes. This has a bigger impact on AA smokers as more smoke menthols (80% v 25%) and more live in poverty. The “menthol effect” explains a significant portion of the black-white difference in smoking cessation. Policy Implications 1. 2. 3. Raise taxes on all smoked tobacco products. Ban menthol as an additive to cigarettes and also ban characterizing flavors in cigars. Plus all the other proven policies: fund comprehensive tobacco control, place pictorial health warnings on packs , implement comprehensive csmoke-free air laws nationally etc..