J. Locke, Op. Cit.: Invocations of Law on Snowy Streets

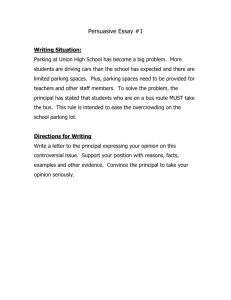

advertisement