Document 12464132

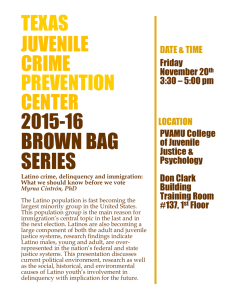

advertisement