‘The Many Faces of Eve’: Unions

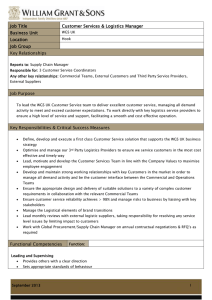

advertisement