The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve... decisionmaking through research and analysis.

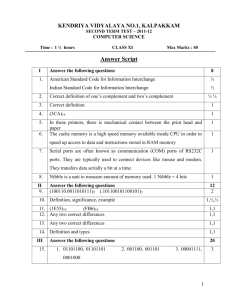

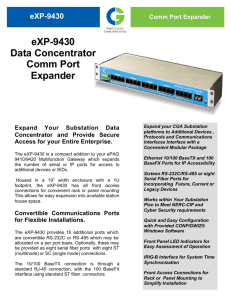

advertisement