Using E-Learning as part of a blended learning approach

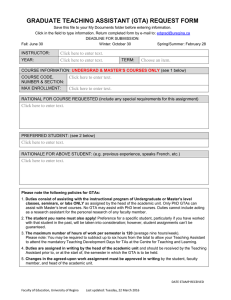

advertisement