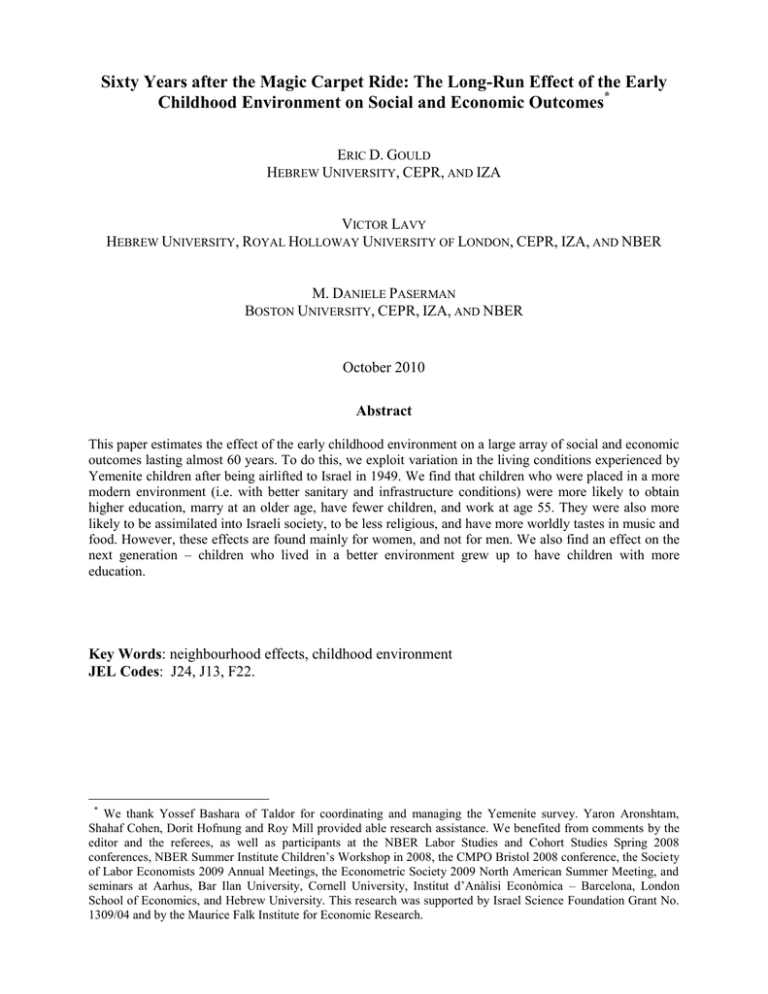

Sixty Years after the Magic Carpet Ride: The Long-Run Effect... Childhood Environment on Social and Economic Outcomes

advertisement