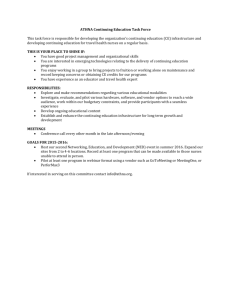

Learning while working in small companies:

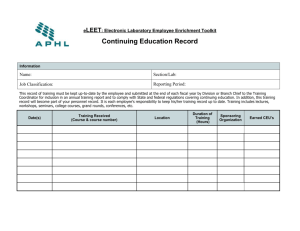

advertisement