THE IMPACT OF GRADUATE PLACEMENTS ON BUSINESSES IN a

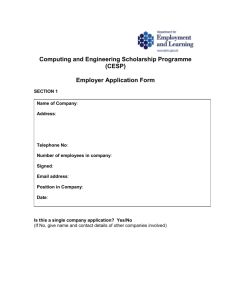

advertisement