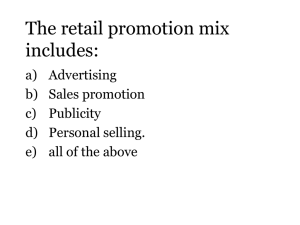

Marketing Mix and Brand Sales in Global Markets:

advertisement