Journal of Applied Psychology

2003, Vol. 88, No. 5, 954 –963

Copyright 2003 by the American Psychological Association, Inc.

0021-9010/03/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.954

Conscientiousness, Autonomy Fit, and Development: A Longitudinal Study

Marcia J. Simmering

Jason A. Colquitt

Louisiana State University

University of Florida

Raymond A. Noe

Christopher O. L. H. Porter

The Ohio State University

Texas A&M University

The authors examined employee development and its relationship with Conscientiousness and person–

environment fit (in terms of needs and supplies of autonomy). They hypothesized that Conscientiousness

would be positively associated with development but only when employees felt that the autonomy

supplied by the organization did not fit their needs. In other words, whereas Conscientiousness could

supply the dispositional resources for development, misfit was needed to create the need for development.

The results supported the authors’ predictions. Conscientiousness was positively related to development

but only when employees were misfits with respect to autonomy. Employee involvement in development

activities was then linked to subsequent fit.

change either the environment (active adjustment) or the way that

he or she behaves in that environment (reactive adjustment). Similarly, a recent model of job crafting proposes that in many jobs

employees can exert some influence in the organization to change

their work tasks and interactions (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001).

Thus, employee development can be a means of changing both

oneself and one’s environment.

A variety of activities are used to promote employee development. These include setting goals for skill improvement, taking

formal courses, assuming challenging job responsibilities, undergoing assessment activities, and engaging in facilitative interpersonal relationships (Birdi, Allan, & Warr, 1997; Noe, 1999).

Whatever the activity, it is critical to build an understanding of

how to promote individuals’ development efforts and how those

efforts result in positive changes within the organization (Baldwin

& Padgett, 1993). Unfortunately, the few studies that have been

conducted on employee development have focused on a limited set

of individual antecedents or contextual antecedents (Birdi et al.,

1997; Maurer & Tarulli, 1994; Noe & Wilk, 1993). Research has

failed to examine the type of individual– context interactions that

predict most types of volitional behavior (e.g., Roberts, Hulin, &

Rousseau, 1978).

In this study, we examined employee development as a function

of both Conscientiousness and person– environment fit with respect to needs and supplies of autonomy. We argued that conscientious individuals should be more likely to engage in development, particularly when they are experiencing person–

environment misfit. Such individuals can use development to

proactively improve their fit, leading to better fit at a later point in

time (see Figure 1). In the sections below we detail the proposed

linkage between Conscientiousness and employee development, as

well as the moderating role of person– environment fit.

Recent changes in the global economy have presented organizations with the challenge of promoting continuous lifelong learning by their workers (London & Mone, 1999; London & Smither,

1999). Such learning is critical because job demands are increasingly dynamic, continually changing as a result of new technologies or increased competition (Hesketh & Neal, 1999). As a result,

today’s employees are expected to become more self-directed in

building their skills and managing their work environments

(Hedge & Borman, 1995). Consequently, employee development

has become an important component of maintaining an effective

workforce.

Employee development is a self-initiated, self-directed means

by which employees improve their competencies and work environment (London, 1989; London & Smither, 1999). As described

by London (1989), employee development consists of activities

that influence personal and professional growth. Developmental

activities can impact personal growth by leading to improvements

in skills and competencies (London, 1989; London & Smither,

1999). They can impact professional growth by leading to improving marketability and promotability. Dawis and Lofquist (1984)

suggested in their theory of work adjustment that in the interest of

increasing one’s fit with the environment, an individual may

Marcia J. Simmering, Rucks Department of Management, E. J. Ourso

College of Business Administration, Louisiana State University; Jason A.

Colquitt, Department of Management, University of Florida; Raymond A.

Noe, Management and Human Resources Department, The Ohio State

University; Christopher O. L. H. Porter, Department of Management,

Texas A&M University.

A draft of this article was presented at the 58th Annual Meeting of the

Academy of Management in Chicago, Illinois, August 1999. We thank

Amy Kristof-Brown, Kenneth G. Brown, Jeffery A. LePine, and Cheri

Ostroff for their helpful comments on a draft of this article.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Marcia J.

Simmering, who is now at the Department of Management and Marketing,

College of Administration and Business, Louisiana Tech University, Ruston, Louisiana 71272. E-mail: MJS@cab.latech.edu

Conscientiousness and Employee Development

Conscientious employees tend to be reliable, hardworking, selfdisciplined, and persevering (McCrae & Costa, 1987). Conscien954

RESEARCH REPORTS

955

Figure 1. Model summarizing study predictions. Dashed line represents administration of the SKILLSCOPE

instrument.

tiousness has been linked to a number of important job outcomes

(Barrick & Mount, 1991) but has yet to be explicitly linked to

employee development. However, Hall’s (1986) model of career

development suggests that achievement orientation, proactivity,

hardiness, and independence will improve an employee’s career

success. These traits are subsumed under the Conscientiousness

factor and support a relationship with employee development.

Surprisingly, empirical research examining the relationship between Conscientiousness and learning-related outcomes has

yielded inconsistent findings. Research has found positive relationships between Conscientiousness and goal commitment, motivation to learn, and learning (Barrick, Mount, & Strauss, 1993;

Colquitt & Simmering, 1998), all of which are necessary for

development to occur. Conversely, Martocchio and Judge (1997)

found a negative relationship between Conscientiousness and

learning, an effect that was mediated by self-deception. Specifically, conscientious individuals were more likely to believe they

were doing better than they truly were—a tendency that harmed

learning. LePine, Colquitt, and Erez (2000) also uncovered detrimental effects for Conscientiousness, with the trait being negatively related to posttraining performance in contexts requiring

adaptability.

Two meta-analyses have added to the equivocal results regarding the relationship between Conscientiousness and learningrelated outcomes. Barrick and Mount’s (1991) meta-analysis on

the Big Five linked Conscientiousness to job proficiency ( ⫽ .23)

and training proficiency ( ⫽ .23). However, Colquitt, LePine, and

Noe (2000) conducted a meta-analytic review of the training

literature that included Conscientiousness and several training

outcomes (e.g., declarative knowledge and skill acquisition). Their

review yielded ⫽ ⫺.01 for Conscientiousness and declarative

knowledge and ⫽ ⫺.05 for Conscientiousness and skill acquisition. The results of both meta-analyses showed that sampling and

measurement error could not fully explain the variance in effect

sizes, suggesting that moderators may affect the relationships

between Conscientiousness and learning-related outcomes.

The Moderating Role of Person–Environment Fit

Many researchers agree that to fully understand and predict

employee behavior, one must examine both the person and the

context (e.g., Chatman, 1989; Roberts et al., 1978). A key issue in

the present study was identifying a potential moderator of the

relationship between Conscientiousness and employee development. We focused on person– environment fit as that moderator.

Whereas Conscientiousness can provide the resources for development (in the form of self-discipline, perseverance, etc.), person–

environment misfit can provide the need for development, as

development activities can be used to proactively restore fit.

Person– environment fit can be generally defined as the compatibility between individuals and the environments in which they

work. Although person– environment fit has traditionally been

examined in terms of its direct effects on outcomes such as work

attitudes, strain, and turnover (e.g., Chan, 1996; Chatman, 1991;

Edwards & Harrison, 1993; Posner, 1992; Posner, Kouzes, &

Schmidt, 1985), recent work has begun to examine fit as a moderator of individual difference effects. Kristof (1996) suggested

that individual differences and fit may interact in their effects on

outcomes. For example, Smith and Rogg (2000) conducted two

studies showing that cognitive ability had a more positive relationship with sales performance when misfit between an employee’s

need for and the presence of unique task–reward characteristics of

the job existed.

Person– environment fit has been operationalized in many ways,

including person– organization fit (e.g., Kristof, 1996) and person–

job fit (e.g., Edwards, 1991). Research on fit has also examined fit

between personality and organizational culture (e.g., Chatman &

Barsade, 1995; Day & Bedeian, 1991; Downey, Hellriegel, &

956

RESEARCH REPORTS

Slocum, 1975) and between individuals’ needs and abilities and

job characteristics (e.g., Edwards & Harrison, 1993). Much of this

research has followed Schneider’s (1987) attraction-selectionattrition (ASA) model, in which he posits that employees are

attracted to organizations that provide a high level of fit, are then

selected by organizations that perceive this fit, and subsequently

leave the organizations if misfit occurs. The ASA model implies

that fit results in positive outcomes and that misfit results in

negative outcomes. Because the ASA model has guided most of

the fit research to date, empirical studies have attempted to demonstrate these effects. For example, several studies have linked fit

to positive work attitudes (e.g., Posner, 1992; Posner et al., 1985),

whereas others have linked misfit to strain and withdrawal (Chan,

1996; Chatman, 1991; Edwards & Harrison, 1993).

By its very nature, the ASA framework deemphasizes the possibility that individuals who experience misfit may change themselves (or their environments) rather than self-selecting out of their

organizations. This is unfortunate because it portrays employees as

reactive rather than proactive. Our contention was that conscientious individuals, when faced with misfit, will respond by proactively engaging in development to improve their fit. We examined

this prediction using needs–supplies fit as the operationalization of

person– environment fit. Needs–supplies fit occurs when a person’s job supplies the characteristics that meet his or her needs

(e.g., Chatman, 1991; Posner, 1992; Posner et al., 1985).

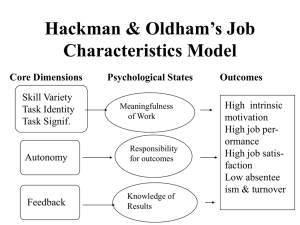

We chose to examine the needs and supplies of autonomy

because research has lacked a systematic investigation of characteristics relevant across a broad range of jobs. Autonomy, defined

as “the degree to which the job provides substantial freedom,

independence, and discretion to the individual in scheduling the

work and in determining the procedures to be used in carrying it

out” (Hackman & Oldham, 1980, p. 79), is an important form of fit

for several reasons. First, development is often triggered by the

existence of too much or too little autonomy, as can be seen in

many models of career progression (e.g., Hall, 1986). Similarly,

reviews of the literature indicate that development can be used to

attain more discretion and control in the future or to cope with

existing levels of job responsibility (e.g., Noe, Wilk, Mullen, &

Wanek, 1997).

Autonomy is also one of the most commonly examined job

characteristics in the person– environment fit literature (e.g., Edwards & Harrison, 1993; Edwards & Rothbard, 1999; Kulik,

Oldham, & Hackman, 1987). Thus, using it in the present study

provides a bridge to research in the area. Moreover, autonomy fit

should become increasingly important as decision making and

control get pushed to lower levels of an organization (Motowidlo

& Schmit, 1999). This trend makes it more likely that some

employees will feel that they have too much autonomy, whereas

others will respond to their newfound control with the desire to

gain more control.

Theoretical Grounding

Our prediction that autonomy misfit will moderate the relationship between Conscientiousness and development can be supported with two different literatures: proactive socialization and

situational strength. Proactive socialization researchers argue that

new employees can engage in specific on-the-job behaviors that

can help improve their skills, increase their understanding of

organizational roles and norms, and build a supportive network of

work relationships (Ashford & Black, 1996; Morrison, 1993; Saks

& Ashforth, 1996; Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). These

behaviors, which can supplement the organization’s existing programs and rituals, include information seeking, feedback seeking,

goal setting, networking, negotiating, framing, practicing desired

behaviors, tracking progress, and self rewarding. The use of such

strategies has been shown to predict task mastery, role clarity,

social integration, anxiety, intrinsic motivation, coping ability, job

satisfaction, and withdrawal (Ashford & Black, 1996; Morrison,

1993; Saks & Ashforth, 1996; Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller,

2000).

Proactive socialization and employee development both involve

the use of self-managed behaviors for improving job skills and

conditions (though proactive socialization focuses exclusively on

newcomers). In fact, many of the actual behaviors are similar,

particularly goal setting, feedback setting, practicing desired behaviors, and tracking progress. Wanberg and Kammeyer-Mueller

(2000) found a significant correlation between Conscientiousness

and two of four proactive behaviors, but its effects were nonsignificant after controlling for other individual and contextual variables. In reflecting on these nonsignificant findings, Wanberg and

Kammeyer-Mueller speculated that “conscientious individuals

may have a tendency to be more confident in socialization experiences and may feel less of a need to seek out information and

feedback” (p. 382).

In other words, conscientious individuals might possess the

resources for proactive behaviors—like socialization or development— but might not see the need for them. We argue that person–

job misfit, with respect to autonomy, could supply that need.

Ashford and Black (1996) showed that autonomy needs (labeled

desire for control in their study) were one trigger of proactive

socialization behaviors. This supports the notion that autonomy

misfit could trigger conscientious individuals to use their perseverance and self-reliance to engage in development activities.

The idea that misfit amplifies the Conscientiousness–

development relationship is also consistent with situational

strength theory (Mischel, 1977; Weiss & Adler, 1984). Mischel

(1977) described strong situations as those in which appropriate

behaviors are clear, skill requirements are uniformly met, and

assessments of the work environment do not vary. Interindividual

variability is low in strong situations, preventing personality variables from predicting behavior. In contrast, weak situations are

marked by cases in which appropriate behaviors are unclear, some

skill requirements may be lacking, and perceptions of the work

environment vary. Here, interindividual variability is high, allowing personality– behavior correlations to emerge.

We hypothesized that the existence of person–job misfit should

create a circumstance in which appropriate behaviors are unclear,

skill requirements may be unmet, and assessments of the work

environment may vary. If so, then the responses of careful, reliable, hardworking, ambitious, and self-reliant individuals will be

more distinct from the responses of careless, undependable, lazy,

and helpless individuals, to use McCrae and Costa’s (1987) conscientiousness descriptors. In contrast, we hypothesized that the

presence of person–job fit should constrain interindividual variability to a greater degree, weakening the Conscientiousness–

development relationship. Thus, as shown in Figure 1, we predicted the following:

RESEARCH REPORTS

Hypothesis 1: The relationship between Conscientiousness

and employee development will be moderated by person–

environment fit, such that the relationship will be more positive where misfit exists for needs and supplies of autonomy.

In stating the above hypothesis, it is important for us to note that

misfit can exist when an employee has too little autonomy and

when an employee has too much autonomy. Both circumstances

constitute weak situations, and both could create the need for

development. Too little autonomy could trigger development activities as a means of attaining more important work assignments

that supply more discretion and control. Too much autonomy

could trigger development activities as a means of honing one’s

skills to cope with job requirements. Unfortunately, research on fit

and stress suggests that development may not occur in the latter

situation. Excess job supplies have been associated with increased

tension, role overload, and role conflict (Edwards, 1996), which

can reduce commitment, well-being, and satisfaction (Bedeian &

Armenakis, 1981; Parasuraman & Alutto, 1984). Development

would likely be impractical in such circumstances, because it

would simply create more demands on the employee. Nonetheless,

our study tested the relationship between Conscientiousness and

development as moderated by both types of misfit.

Employee Development and Subsequent Fit

Implicit in our proposal that conscientious individuals will respond to misfit by engaging in development is the assumption that

development will improve fit at a subsequent time. To support a

relationship between development and subsequent fit, we again

turn to proactive socialization. Saks and Ashforth’s (1997) review

of the socialization literature introduced a multilevel process

model of organizational socialization. In that model, Saks and

Ashforth argued that proactive strategies and behaviors would lead

to increases in information and learning, which would then lead to

improved person–job fit. Kristof (1996) made a similar prediction

in her review of the fit literature.

We hypothesized that developmental activities could alter subsequent person–job fit via two mechanisms. For individuals with

too little autonomy, the completion of coursework, job challenges,

and assessment activities could lead to more job latitude, more

enriching assignments, or more promotions, thereby increasing

supplies of autonomy. For individuals with too much autonomy,

those same activities could improve self-confidence to the point at

which more autonomy is needed and desired. In one case, fit is

restored by the alteration of subsequent supplies; in the other case,

it is restored by the alteration of subsequent needs. Thus, as shown

in Figure 1, we predicted the following:

Hypothesis 2: Employee development will be associated with

increased subsequent needs–supplies fit in terms of

autonomy.

957

1993; London & Beatty, 1993). It typically involves providing employees

with feedback about their skill strengths and weaknesses from multiple

sources, including supervisors, peers, and themselves (Hazucha et al.,

1993). The intervention was used in this study to create the opportunity for

developmental activities while preserving natural variance that could be

predicted by Conscientiousness and misfit.

Participants

Participants were 83 managers working in 21 different industries; 78%

were male, and 22% were female. They each had an average of six people

who directly reported to them, and they each had worked in an average of

two companies prior to working for their current employer. Average tenure

in the current organization was over 5 years, and the average age of the

sample was 32 years. This sample is particularly appropriate for this study

because researchers in the areas of person– environment fit and development have long emphasized the need for samples that span several organizations and occupations (e.g., Downey et al., 1975). The study participants were enrolled in an executive Masters of Business Administration

(MBA) program at Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan.

Procedure

The procedure included three phases: before, during, and after the 360°

feedback was received by the participants. The procedures in these phases

are described in Table 1.

Prefeedback phase. Upon acceptance to the MBA program, participants took part in a variety of orientation exercises, including one related

to their Managerial Skills course. This exercise required participants to

complete a 360° feedback instrument, called SKILLSCOPE (2002),1 which

was provided and scored by the Center for Creative Leadership, Greensboro, North Carolina. Participants rated their own skills and weaknesses

and asked their supervisors and peers to complete the instrument. Several

weeks later, the participants completed a measure of person– environment

fit and gave their managers a measure of development activities. On this

measure, managers were asked to evaluate the development activities of the

study participants over the past 6 months. The measures were mailed back

to the researchers and were not shared with the participants. These surveys

provided a baseline measure of person– environment fit and development.

Feedback phase. Approximately 1 month later, participants received

an individualized SKILLSCOPE feedback report during the first week of

their Managerial Skills course. The instructor explained how to interpret

the feedback report, described various types of developmental activities,

and explained how to create a development plan. This communication

process was similar to that used by most organizations, in which only

employees see the results and in which subsequent development is not

closely monitored by the organization (London & Smither, 1995).

Postfeedback phase. Six months after the initial measure of fit and

employee development, participants were again asked to assess their fit.

They also completed a measure of Conscientiousness. As before, participants were asked to give a questionnaire to their manager to evaluate the

participants’ development activities. The managers’ survey responses were

mailed directly to the researchers and were never seen by the study

participants.

Measures

Method

Conscientiousness. Conscientiousness was measured using Costa and

McCrae’s (1992) 48-item revised NEO Personality Inventory scale (1 ⫽

We conducted this study in the context of a 360° feedback intervention.

Using 360° feedback to facilitate development is an approach that has

increased in popularity in recent years (Hazucha, Hezlett, & Schneider,

1

Center for Creative Leadership, CCL, its logo, and SKILLSCOPE are

registered trademarks owned by the Center for Creative leadership. Copyright 2003 Center for Creative Leadership. All rights reserved.

Study Context

RESEARCH REPORTS

958

Table 1

Timeline of Study Procedures

organization (i.e., tenure) and the number of employees who directly

reported to them in their present position (i.e., span of control).

Study phase

Procedure

Prefeedback

Participants completed the SKILLSCOPE instrument.

Participants completed initial person–environment fit

measures.

Supervisors rated initial development.

SKILLSCOPE feedback results were returned.

Participants again completed person–environment fit

measures, along with the Conscientiousness

measure.

Supervisors again rated development.

Feedback

Postfeedback

Note. Time period between pre- and postfeedback survey administrations

was 6 months. SKILLSCOPE (2002) is a 360° feedback instrument that

was provided and scored by the Center for Creative Leadership, Greensboro, North Carolina.

strongly disagree to 5 ⫽ strongly agree). Responses to this Conscientiousness measure tend to be remarkably stable over time, with test–retest

reliability estimated at .83 (Costa & McCrae, 1992).

Autonomy needs. A five-item scale, based on the independence subscale of the Work Aspect Preference Scale (Pryor, 1998), measured the

amount of autonomy the employees felt was acceptable in their current jobs

(one component of autonomy fit). Employees answered the question “How

much of the characteristic do you personally feel is acceptable?” for items

including “The opportunity to work as fast or as slowly as I like” and “The

opportunity to do my work in my own way” (1 ⫽ none at all to 5 ⫽ very

much).

Autonomy supplies. A five-item scale, based on the independence

subscale of the Work Aspect Preference Scale (Pryor, 1998), measured the

amount of autonomy the employees felt was present in their current jobs,

which is the other component of autonomy fit). Employees answered the

question “How much of the characteristic is present in your job now?,”

referencing the same five items used in the Autonomy Needs scale (1 ⫽

none at all to 5 ⫽ very much).

Development. The participants’ managers were asked to rate the degree to which the participants were involved in development activities over

the previous 6 months using 10 items from Noe’s (1996) study. Participants’ managers were told “The purpose of this survey is to collect

information about the extent to which

has participated in

various types of career development activities during the past six months.

Please use the following scale in making your responses: (1 ⫽ little to 5 ⫽

a great deal).” Items began with “To what extent has this individual during

the past six months:” and included endings such as “asked you for projects,

committee work, or special assignments in order to improve skills or

acquire new ones,” “sought information from you regarding personal

and/or professional development courses,” “asked you for feedback regarding his/her skill weaknesses (other than the SKILLSCOPE feedback you

recently completed),” and “changed an aspect of his/her behavior because

of feedback.”

360° feedback. Although not relevant to the hypotheses, it was necessary to control for the SKILLSCOPE feedback participants received between the two fit and development measurement administrations. The

SKILLSCOPE feedback focused on broad managerial skills such as managing conflict, negotiating, building relationships, selecting and developing

people, developing influence, being flexible, and coping with pressure. For

each item, respondents indicated whether the item was a strength (1) or an

area where there was development needed (0). Our analyses controlled for

the supervisor, peer, and self SKILLSCOPE ratings.

Other controls. Because participants’ tenure and span of control were

expected to correlate with autonomy supplies and development, participants indicated the number of months they had worked at their present

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations for

all variables are shown in Table 2. Notably, the zero-order relationship between Conscientiousness and postfeedback development (r ⫽ .17, p ⬍ .10, one-tailed) fell between Barrick and

Mount’s (1991) ⫽ .23 for training proficiency and Colquitt et

al.’s (2000) ⫽ ⫺.01 and ⫽ ⫺.05 for declarative knowledge and

skill acquisition. Finally, only the self ratings in the SKILLSCOPE

feedback were significant predictors of subsequent development

(r ⫽ ⫺.33, p ⬍ .05, one-tailed), with lower self ratings associated

with increased subsequent development.

Conscientiousness and Misfit as Predictors of

Development

Hypothesis 1 predicted that the relationship between Conscientiousness and postfeedback development would be moderated by

autonomy fit, with Conscientiousness more positively related to

development for individuals experiencing misfit. To test this, we

analyzed fit as the interaction of two separate variables: prefeedback autonomy needs and supplies. By using the two fit components as separate variables in a moderated regression, we avoided

problems related to the use of difference scores (e.g., poor reliability, questionable construct validity, and difficulties in interpretability; Edwards, 1994; Edwards & Parry, 1993). One should recall

that we speculated that Conscientiousness would predict development more when individuals had too little autonomy than it would

when they had too much. This type of analysis allowed these

differences in types of fit and types of misfit to be directly

examined.

Thus, the test of Hypothesis 1 regressed postfeedback development onto the following variables in the following steps:

1.

tenure and span of control,

2.

supervisor, peer, and self SKILLSCOPE feedback,

3.

prefeedback development,

4.

Conscientiousness,

5.

the prefeedback needs and supplies fit components,

6.

the 2 two-way interaction terms using Conscientiousness

and the fit components,

7.

the two-way interaction between the fit components, and

8.

the three-way interaction of Conscientiousness and the fit

components.

Support for Hypothesis 1 would be found if the interaction term in

the final step contributed significant incremental variance explained, with the pattern of the effect as predicted.

The regression results are shown in Table 3. As shown in the

eighth step, the prefeedback autonomy fit interaction did interact

12

—

11

—

.45**

RESEARCH REPORTS

959

Table 3

Moderated Regression Results for Hypothesis 1

Development

(postfeedback)

⌬R2

R2

.02

.08

.01

.01

⫺.06

⫺.04

⫺.33*

.12*

.13

Development (prefeedback)

.46*

.19*

.32*

Conscientiousness

.20*

.04*

.36*

(.71)

.06

.10

1

Tenure

Span of control

(.67)

.44**

.03

.19*

2

Supervisor 360° feedback

Peer 360° feedback

Self 360° feedback

(.84)

⫺.02

.25**

.06

.09

3

4

(.97)

⫺.33**

.11

.02

.10

⫺.07

5

6

(.74)

⫺.10

⫺.01

.01

.02

.03

.12

6

7

8

9

10

Regression step

7

(.96)

.24**

.18*

⫺.13

⫺.13

.01

⫺.13

.07

⫺.19

.13

.02

.38*

Conscientiousness ⫻ Autonomy Needs

Conscientiousness ⫻ Autonomy Supplies

⫺.02

.04

.00

.38*

Autonomy Needs ⫻ Autonomy Supplies

⫺.04

.00

.38*

Conscientiousness ⫻ Autonomy

Needs ⫻ Autonomy Supplies

⫺.39*

.05*

.43*

Note. N ⫽ 66 after listwise deletion.

* p ⬍ .05.

Note. N ⫽ 66 after listwise deletion. Numbers in parentheses represent coefficient alpha reliabilities.

* p ⬍ .10, one-tailed. ** p ⬍ .05, one-tailed.

(.74)

⫺.11

.03

⫺.11

.10

.53**

.62**

.12

.15

(.58)

.62**

⫺.09

.07

⫺.06

.02

.53**

.34**

.28**

.34**

(.84)

.15

.14

⫺.02

⫺.07

⫺.25**

.51**

.07

.23**

⫺.01

⫺.00

(.88)

⫺.05

⫺.04

⫺.14

.09

.01

.04

.17*

⫺.08

⫺.10

.03

.01

0.32

0.77

0.53

0.75

0.15

0.14

0.16

0.80

0.53

0.68

4.26

18.44

3.58

2.86

3.57

3.23

0.84

0.53

0.77

3.03

3.67

3.22

5.43

5.98

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

Conscientiousness

Development (prefeedback)

Autonomy needs (prefeedback)

Autonomy supplies (prefeedback)

Supervisor 360° feedback

Peer 360° feedback

Self 360° feedback

Development (postfeedback)

Autonomy needs (postfeedback)

Autonomy supplies (postfeedback)

Tenure

Span of control

SD

M

Variable

Table 2

Means, Standard Deviations, and Zero-Order Correlations

1

2

3

4

5

8

Autonomy needs (prefeedback)

Autonomy supplies (prefeedback)

with Conscientiousness in relating to development (⌬R2 ⫽ .05,

p ⬍ .05). One should note that although this interaction was

significant, the separate components of fit were not significantly

correlated with Conscientiousness; this indicates that it is indeed

the combination of fit and Conscientiousness that relates to development and not simply an increase in autonomy needed or autonomy supplied. The pattern of this effect can be seen in Table 4,

which lists the four possible configurations of autonomy fit: (a) fit

in which autonomy needs and supplies are both high; (b) misfit in

which supplies exceed needs; (c) misfit in which needs exceed

supplies; and (d) fit in which needs and supplies are both low.

These subgroups were formed by performing median splits of the

prefeedback autonomy needs and autonomy supplies variables.

Table 4 clearly shows that the correlation between Conscientiousness and development is higher where misfit exists (r ⫽ .36 and

Table 4

Correlation Between Conscientiousness and Development

Fit or misfit?

Fit

Misfit

Misfit

Fit

Fit type

High autonomy needs,

high supplies

Low autonomy needs,

high supplies

High autonomy needs,

low supplies

Low autonomy needs,

low supplies

rConscientiousness,development

.00

.36

.40

⫺.11

Note. Subgroups were created by performing median splits of the

prefeedback autonomy needs and autonomy supplies variables.

RESEARCH REPORTS

960

r ⫽ .40) than it is where fit exists (r ⫽ .00 and r ⫽ ⫺.11), thereby

supporting Hypothesis 1. Indeed, the misfit correlations exceeded

the corrected effect sizes from Barrick and Mount’s (1991) study,

whereas the fit correlations approximately matched Colquitt et

al.’s (2000) results.

Development as a Predictor of Subsequent Fit

Hypothesis 2 predicted that postfeedback development would be

associated with increased postfeedback autonomy fit. As with the

other analyses, we operationalized fit using autonomy needs and

supplies as two separate variables. Many of the same criticisms

leveled against difference scores as independent variables are also

relevant for difference scores as dependent variables. Edwards

(1995) outlined a procedure that allows the components of a

difference score to remain distinct while being used as a dependent

variable. The procedure uses multivariate regression that, like

multivariate analysis of variance, allows one to test the effects of

predictors on two separate variables while conducting multivariate

tests of the association between the predictors and components as

a set.

We assessed the effect of postfeedback development on postfeedback autonomy needs and supplies (as a set) while controlling

for tenure, span of control, and prefeedback autonomy needs and

supplies. The multivariate effect of a predictor can be gauged using

several statistics, and we reported Hotelling’s Trace, Wilks’s

lambda, and eta squared. Multivariate regression further allows for

the decomposition of the overall effect, allowing insight into which

component(s) of fit are affected and how. For example, if participants’ initial misfit was characterized by too little autonomy, fit

could be restored by increasing subsequent autonomy supplies.

The multivariate regression results are presented in Tables 5

and 6. The test of Hypothesis 2 can be seen in the Development

(postfeedback) row of Table 5. Postfeedback development did

have a statistically significant multivariate effect on the two autonomy fit components, F(2, 60) ⫽ 3.00, p ⬍ .05. These results

can be interpreted as univariate regression output would be interpreted. The observed multivariate effect was primarily due to

development’s positive relationship with postfeedback autonomy

supplies ( ⫽ .21, p ⬍ .05). Thus, development improved fit

primarily by increasing supplies of autonomy.

Discussion

This study examined the relationships among Conscientiousness, person– environment fit, and development in a longitudinal

study, using employees from several different organizations. Notably, conscientious individuals were more likely to engage in

development activities but only when they felt that their jobs were

not meeting their autonomy needs. Considering the entire sample,

the relationship between Conscientiousness and development only

approached significance, falling between the levels of Barrick and

Mount’s (1991) and Colquitt et al.’s (2000) meta-analyses. The

correlation was much higher for those experiencing misfit.

The strongest correlation between Conscientiousness and development was exhibited by participants who possessed too little

autonomy. Our results showed that fit improved for those individuals who engaged in development, because development activities

led to increased supplies of autonomy in their jobs. Autonomy

supplies increased by .13 from prefeedback to postfeedback conditions for the most conscientious individuals who engaged in the

most development (those above the median on Conscientiousness

and development). These supply changes illustrate the exchange

nature of development from the individual and organizational

perspective, as participation in development seemed to be met with

the employees’ increased ability to do work at the pace and in the

manner of their choosing. Because the development did nothing to

alter employees’ autonomy needs, the result was improved person–

environment fit. This supports our prediction that conscientious

individuals can use development as a means of proactively reducing misfit, rather than reactively turning over, as the ASA model

would predict.

Although the Conscientiousness–fit interaction results supported our predictions, conscientious individuals who possessed

too much autonomy also tended to engage in development activities. This was somewhat surprising, because research on person–

job fit has linked excess supplies to increased tension, role overload, and role conflict (Edwards, 1996). Our results suggest that

development activities could further exacerbate misfit for those

individuals by increasing supplies and thereby widening the

needs–supplies gap. It may be that employees undertook development to increase their skills to cope with job demands. However,

if development ultimately results in even more supplies of autonomy, a vicious cycle could be created. Thus, future research should

continue to examine how conscientious individuals react when

faced with too much autonomy.

These results make theoretical contributions to both the person–

environment fit and employee development literatures. Research

on fit has cast the employee in a reactive light in which misfit is

met with strain and eventual turnover. The socialization literature

offers an important lesson in this regard, as reactive research on

Table 5

Multivariate Regression Results for Hypothesis 2

Tests of multivariate effects on autonomy needs and autonomy

supplies (postfeedback)

Variable

Hotelling’s

trace

⌳

F

2

Tenure

Span of control

Autonomy needs (prefeedback)

Autonomy supplies (prefeedback)

Development (postfeedback)

.01

.00

.17

.48

.10

.99

.99

.86

.68

.91

0.38

0.04

5.19*

14.53*

3.00*

.01

.00

.15*

.32*

.09*

RESEARCH REPORTS

961

Table 6

Multivariate Regression Parameter Estimates for Hypothesis 2

Autonomy needs

(postfeedback)

Variable

Autonomy supplies

(postfeedback)

t

t

Parameter estimates

Tenure

Span of control

Autonomy needs (prefeedback)

Autonomy supplies (prefeedback)

Development (postfeedback)

⫺.08

.03

.43*

.26*

⫺.06

⫺0.70

0.29

3.15*

1.98*

⫺0.60

⫺.07

.02

⫺.02

.65*

.21*

⫺0.67

0.15

⫺0.14

5.36*

2.22*

Note. N ⫽ 68 after listwise deletion.

* p ⬍ .05.

organizational rituals and practices has been balanced by proactive

research on newcomers’ strategies and behaviors (Ashford &

Black, 1996; Morrison, 1993; Saks & Ashforth, 1996; Wanberg &

Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). Just as newcomers can rely on goal

setting, feedback seeking, networking, practicing behaviors, and

tracking progress to increase person–job fit, established employees

can use similar strategies to improve their fit levels.

Moreover, this study is unique in that we did not view fit as

uniformly positive, because fit seemed to stifle conscientious individuals’ developmental activities. We therefore suggest that fit

researchers devote further attention to the potential “dark sides” of

fit (e.g., Schneider, Smith, & Goldstein, 1994). Similarly, our

study provides evidence that Conscientiousness is not always

positively related to work behaviors, particularly those relevant to

learning (Colquitt et al., 2000; LePine et al., 2000; Martocchio &

Judge, 1997). Scholars may need to rely more on Person ⫻

Situation approaches to illustrate when Conscientiousness can and

cannot have beneficial effects.

From an applied perspective, although organizations’ exuberance to “win the war for talent” may have them focusing on using

resources for formal development programs (e.g., mentoring and

job experiences), our results suggest that informal development

behaviors are also important. Behaviors such as asking for project

or committee work and seeking feedback regarding skill weaknesses may have a payoff in increased person–job fit. To the extent

that fit reduces (rather than facilitates) turnover, informal development behaviors can result in cost savings for the organization.

This study has several strengths: a field sample with participants

from many different organizations in several different industries, a

longitudinal design that controlled for initial development and fit

levels, and the use of multiple sources to prevent same source bias.

Nevertheless, our study has some limitations that should be noted.

Our sample had an average age of 32 years, so most participants

were in the relatively early stages of their organizational progression. The extent to which our findings would generalize to older

employees at later career stages is an empirical question. In addition, the employees who participated in the study were enrolled in

an executive MBA program and were, in effect, already engaged in

one form of development prior to beginning the study. The nature

of this sample may have created some degree of range restriction

in development and Conscientiousness. The adult norms for conscientiousness are 123.10, with a standard deviation of 17.6 (Costa

& McCrae, 1992). In our sample, Conscientiousness item sums

were slightly higher (170.29), with some range restriction

(SD ⫽ 15.94). This difference in means and standard deviations is

to be expected, because the participants in this study came from an

executive population. However, this range restriction could only

prevent us from detecting statistically significant effects, so our

results are likely to be conservative tests of our hypotheses.

References

Ashford, S. J., & Black, J. S. (1996). Proactivity during organizational

entry: The role of desire for control. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81,

199 –214.

Baldwin, T. T., & Padgett, M. Y. (1993). Management development: A

review and commentary. In C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (Eds.),

International review of industrial and organizational psychology

(Vol. 8, pp. 35– 85). New York: Wiley.

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44,

1–26.

Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K., & Strauss, J. P. (1993). Conscientiousness

and performance of sales representatives: Test of the mediation effects

of goal setting. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 715–722.

Bedeian, A. G., & Armenakis, A. A. (1981). A path-analytic study of the

consequences of role conflict and ambiguity. Academy of Management

Journal, 24, 417– 425.

Birdi, K., Allan, C., & Warr, P. (1997). Correlates and perceived outcomes

of four types of employee development activity. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 82, 845– 857.

Chan, D. (1996). Cognitive misfit of problem-solving style at work: A facet

of person– organization fit. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 68, 194 –207.

Chatman, J. A. (1989). Improving interactional organizational research: A

model of person– organization fit. Academy of Management Review, 14,

333–349.

Chatman, J. A. (1991). Matching people and organizations: Selection and

socialization in public accounting firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 459 – 484.

Chatman, J. A., & Barsade, S. G. (1995). Personality, organizational

culture, and cooperation: Evidence from a business simulation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40, 423– 443.

Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., & Noe, R. A. (2000). Toward an integrative

theory of training motivation: A meta-analytic path analysis of 20 years

of research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 678 –707.

Colquitt, J. A., & Simmering, M. J. (1998). Conscientiousness, goal

962

RESEARCH REPORTS

orientation, and motivation to learn during the learning process: A

longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 654 – 665.

Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). The NEO PI–R professional

manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Dawis, R. V., & Lofquist, L. H. (1984). A psychological theory of work

adjustment. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Day, D. V., & Bedeian, A. G. (1991). Work climate and Type A status as

predictors of job satisfaction: A test of the interactional perspective.

Journal of Vocational Behavior, 38, 39 –52.

Downey, H. K., Hellriegel, D., & Slocum, J. W., Jr. (1975). Congruence

between individual needs, organizational climate, job satisfaction and

performance. Academy of Management Journal, 18, 149 –155.

Edwards, J. R. (1991). Person–job fit: A conceptual integration, literature

review, and methodological critique. In C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson

(Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology

(Vol. 6, pp. 283–357). New York: Wiley.

Edwards, J. R. (1994). The study of congruence in organizational behavior

research: Critique and a proposed alternative. Organizational Behavior

and Human Decision Processes, 58, 51–100.

Edwards, J. R. (1995). Alternatives to difference scores as dependent

variables in the study of congruence in organizational research. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 64, 307–324.

Edwards, J. R. (1996). An examination of competing versions of the

person– environment fit approach to stress. Academy of Management

Journal, 39, 292–339.

Edwards, J. R., & Harrison, R. V. (1993). Job demands and worker health:

Three-dimensional reexamination of the relationship between person–

environment fit and strain. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 628 – 648.

Edwards, J. R., & Parry, M. E. (1993). On the use of polynomial regression

equations as an alternative to difference scores in organizational research. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 1577–1613.

Edwards, J. R., & Rothbard, N. P. (1999). Work and family stress and

well-being: An examination of person– environment fit in the work and

family domains. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 77, 85–129.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1980). Work redesign. Reading, MA:

Addison Wesley.

Hall, D. T. (1986). Breaking career routines: Midcareer choice and identity

development. In D. T. Hall (Ed.), Career development in organizations

(pp. 120 –159). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hazucha, J. R., Hezlett, S. A., & Schneider, R. J. (1993). The impact of

360-degree feedback on management skills development. Human Resource Management, 32, 325–351.

Hedge, J. W., & Borman, W. C. (1995). Changing conceptions and practices in performance appraisal. In A. Howard (Ed.), The changing nature

of work (pp. 451– 482). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hesketh, B., & Neal, A. (1999). Technology and performance. In D. R.

Ilgen & E. D. Pulakos (Eds.), The changing nature of performance:

Implications for staffing, motivation, and development (pp. 21–55). San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kristof, A. L. (1996). Person– organization fit: An integrative review of its

conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Personnel Psychology, 49, 1– 49.

Kulik, C. T., Oldham, G. R., & Hackman, J. R. (1987). Work design as an

approach to person– environment fit. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 31, 278 –296.

LePine, J. A., Colquitt, J. A., & Erez, A. (2000). Adaptability to changing

task contexts: Effects of general cognitive ability, conscientiousness, and

openness. Personnel Psychology, 53, 563–594.

London, M. (1989). Managing the training enterprise. San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass.

London, M., & Beatty, R. W. (1993). 360-degree feedback as a competitive

advantage. Human Resource Management, 32, 353–372.

London, M., & Mone, E. M. (1999). Continuous learning. In D. R. Ilgen &

E. D. Pulakos (Eds.), The changing nature of performance: Implications

for staffing, motivation, and development (pp. 119 –153). San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass.

London, M., & Smither, J. (1995). Can multisource feedback change

perceptions of goal accomplishment, self-evaluations, and performancerelated outcomes? Theory-based applications and directions for research.

Personnel Psychology, 48, 803– 840.

London, M., & Smither, J. (1999). Career-related continuous learning:

Defining the construct and mapping the process. In G. R. Ferris (Ed.),

Research in personnel and human resources management (Vol. 17, pp.

81–121). Stamford, CT: JAI Press.

Martocchio, J. J., & Judge, T. A. (1997). Relationship between conscientiousness and learning in employee training: Mediating influences of

self-deception and self-efficacy. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82,

764 –773.

Maurer, T. J., & Tarulli, B. (1994). Investigation of perceived environment,

perceived outcome, and person variables in relationship to voluntary

development activities by employees. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 3–14.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1987). Validation of the five-factor

model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 81–90.

Mischel, W. (1977). The interaction of person and situation. In D. Magnusson & N. S. Endler (Eds.), Personality at the crossroads: Current

issues in interactional psychology (pp. 333–352). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Morrison, E. W. (1993). Longitudinal study of the effects of information

seeking on newcomer socialization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78,

173–183.

Motowidlo, S. J., & Schmit, M. J. (1999). Performance assessment in

unique jobs. In D. R. Ilgen & E. D. Pulakos (Eds.), The changing nature

of performance (pp. 56 – 85). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Noe, R. A. (1996). Is career management related to employee development

and performance? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 17, 119 –133.

Noe, R. A. (1999). Employee training and development. Burr Ridge, IL:

Irwin/McGraw-Hill.

Noe, R. A., & Wilk, S. L. (1993). Investigation of the factors that influence

employees’ participation in development activities. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 78, 291–302.

Noe, R. A., Wilk, S. L., Mullen, E. J., & Wanek, J. E. (1997). Employee

development: Issues in construct definition and investigation of antecedents. In J. K. Ford (Ed.), Improving training effectiveness in work

organizations (pp. 153–192). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Parasuraman, S., & Alutto, J. A. (1984). Sources and outcomes of stress in

organizational settings: Toward the development of a structural model.

Academy of Management Journal, 27, 333–351.

Posner, B. Z. (1992). Person– organization values congruence: No support

for individual differences as a moderating influence. Human Relations, 45, 351–361.

Posner, B. Z., Kouzes, J. M., & Schmidt, W. H. (1985). Shared values

make a difference: An empirical test of corporate culture. Human Resource Management, 24, 293–309.

Pryor, R. G. L. (1998). Manual for the Work Aspect Preference Scale.

Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Roberts, K. H., Hulin, C. L., & Rousseau, D. M. (1978). Developing an

interdisciplinary science of organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Saks, A. M., & Ashforth, B. E. (1996). Proactive socialization and behavioral self-management. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 48, 301–325.

Saks, A. M., & Ashforth, B. E. (1997). Organizational socialization:

Making sense of the past and present as a prologue for the future.

Journal of Vocational Behavior, 51, 234 –279.

Schneider, B. (1987). The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, 40, 437– 453.

Schneider, B., Smith, D. B., & Goldstein, H. W. (1994, August). The “dark

RESEARCH REPORTS

side” of “good fit.” Paper presented at the 54th Annual Meeting of the

National Academy of Management, Dallas, TX.

SKILLSCOPE. (2002). Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.

Smith, R., & Rogg, K. L. (2000). Subjective person–job fit and sales

performance: Its predictive validity and role as a moderator of the

cognitive ability–performance relationship. Manuscript submitted for

publication.

Wanberg, C. R., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2000). Predictors and

outcomes of proactivity in the socialization process. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 85, 373–385.

Weiss, H. M., & Adler, S. (1984). Personality and organizational behavior.

963

In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational

behavior (Vol. 6, pp. 1–50). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning

employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management

Review, 26, 179 –201.

Received August 5, 2002

Revision received December 19, 2002

Accepted January 28, 2003 䡲