CRIMINALIZATION AND STABILITY IN CENTRAL ASIA AND SOUTH CAUCASUS Phil Williams INTRODUCTION

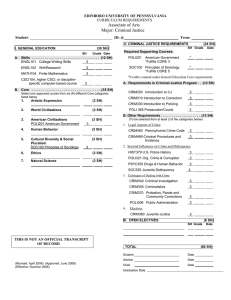

advertisement