Improving DoD Support to FEMA’s All-Hazards Plans

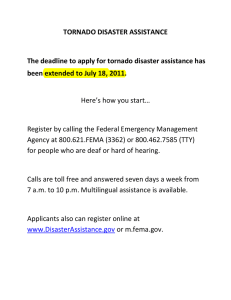

advertisement