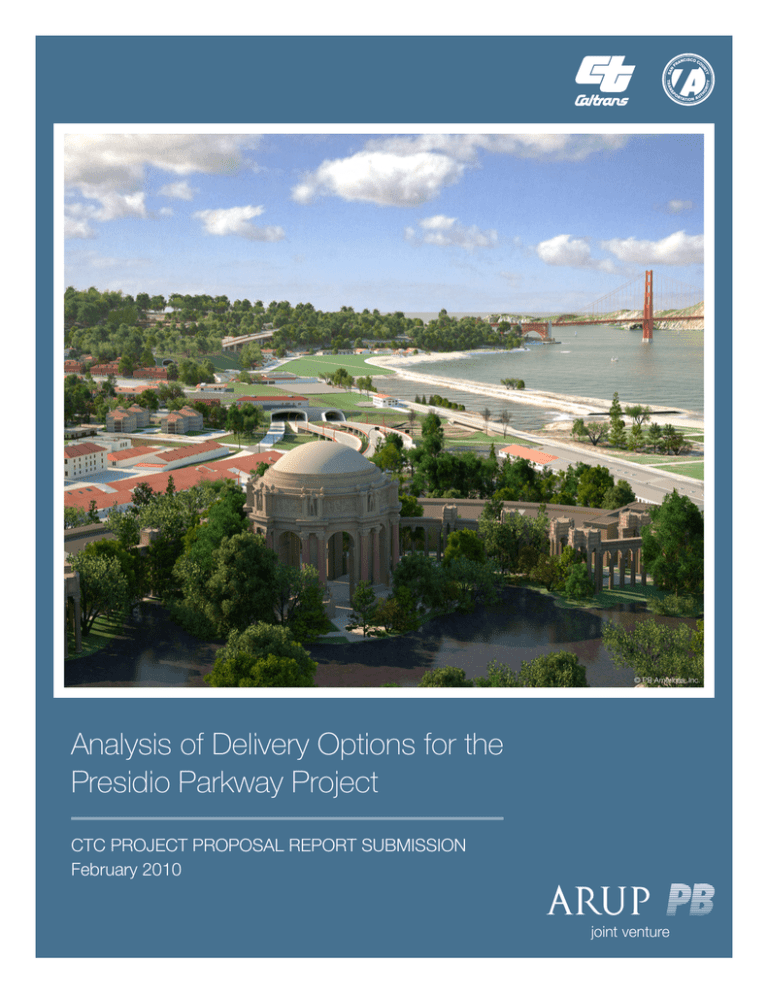

Analysis of Delivery Options for the Presidio Parkway Project February 2010

advertisement