LIABILITY AND ORGANIZATIONAL CHOICE Abstract

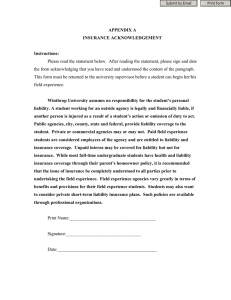

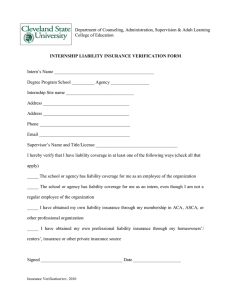

advertisement