Consequential Responsibility for Client Wrongs: Lehman

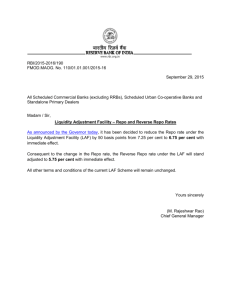

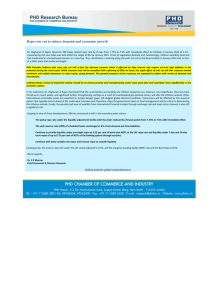

advertisement