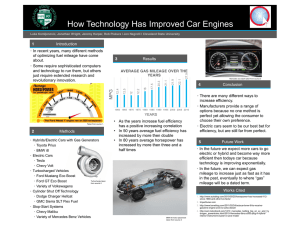

SPECIAL REPORT 299: REDUCING TRANSPORTATION GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS AND ENERGY COMSUMPTION:

advertisement