Rooted transnational publics: Integrating foreign ties and civic activism

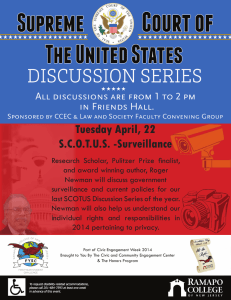

advertisement