Signaling without Certification: The Critical Role of Civil Society Scrutiny Working Paper

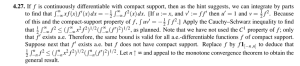

advertisement