International D ifferences in the Size and Roles of Corporate Headquarters: An

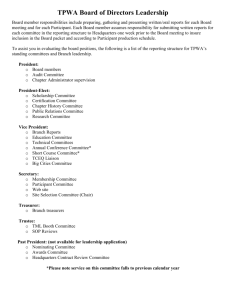

advertisement