The Food Stamp Shelter Deduction: Helping Households with High Housing Burdens

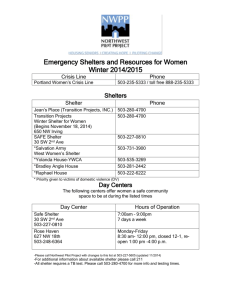

advertisement