Historical Insights

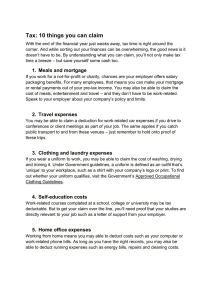

advertisement