The Supreme Court Judgment

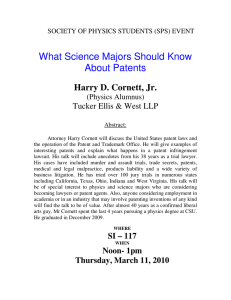

advertisement