Do reductions of standard hours affect employment transitions? : Rafael Sánchez

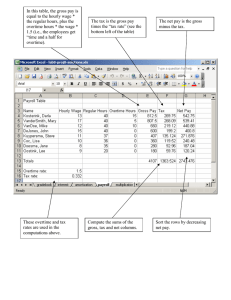

advertisement