Explaining Cross-Racial Di¤erences in the Educational Gender Gap Esteban M. Aucejo

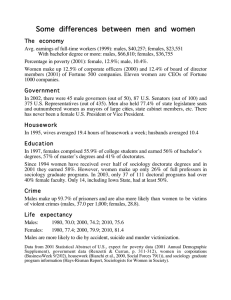

advertisement