CONTRACT DESIGN WITH MOTIVATED AGENTS: EXPERIMENTAL EVIDENCE Lea Cassar June 4, 2014 Abstract

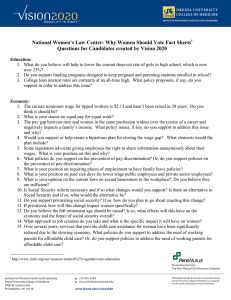

advertisement

CONTRACT DESIGN WITH MOTIVATED AGENTS: EXPERIMENTAL EVIDENCE

Lea Cassar∗

June 4, 2014

Abstract

Do employers take advantage of workers’ intrinsic motivation by offering lower wages?

Do they treat monetary incentives and the choice of job characteristics (i.e., the mission)

as substitutes to motivate effort? I address these questions in a laboratory experiment

in which principals can pay the agents to work for either their preferred charity or that

of the principal. The results show that: a) conditional on wage, agents exert more effort when they work for their preferred charity; b) the principals anticipate the agents’

intrinsic motivation and use it to offer lower wages; c) the principals are more likely to

let the agents work for their preferred charity if they can take advantage of their intrinsic

motivation. Overall, these findings provide experimental support for the predictions of

standard contract theory models with motivated agents.

∗

University of Zürich, Blümlisalpstrasse 10, CH-8006, Zürich, Switzerland. Email: lea.cassar@econ.uzh.ch.

Financial support from the Science of Philanthropy Initiative is gratefully acknowledged. I would like thank

in particular Roberto Weber for his excellent supervision. The paper has also benefited from comments and

discussions with Bjorn Bartling, Ernesto Dal Bo, Florian Engl, Florian Englmaier, Holger Herz, David Huffman,

Michael Kosfeld, Nick Netzer, Eldar Shafir, Klaus Schmidt, Christian Zehnder, and with participants at Micro

Economic Workshop at the University of Munich, at the Workshop in Behavioral Economics and Experimental

Research at EPFL, and at the Zurich Workshop of Economics 2013.

Recent empirical evidence has shown that the mission of a job can have a positive effect

on workers’ effort: everything else being equal, workers who believe in the mission of their

job, are willing to exert more effort (Carpenter and Gong, 2013; Besley and Ghatak, 2013;

Tonin and Vlassopoulos, 2014; Gerhards, 2013; Fehrler and Kosfeld, 2013). It is still an open

question, however, how this effort premium affects the design of contracts offered by employers

to motivated workers. Do employers take advantage of workers’ intrinsic motivation by offering

lower wages? Do they treat monetary incentives and the choice of the job mission as substitutes

to motivate effort? These are the two main questions of this paper. The answers to these

questions are not only relevant for the study of non-monetary incentives in organizations but

also for our understanding of wage differentials across occupations and sectors.

Based on the assumptions of standard contract theory models with motivated agents (Besley

and Ghatak, 2005; Delfgaauw and Dur, 2007, 2008; Cassar, 2014), the answer to both questions

should be positive. In a setting where the job mission is exogenous, Besley and Ghatak (2005)

shows that it is optimal for a principal to offer lower monetary incentives if he is matched with

an agent who shares his same mission preferences. Similarly, in a setting where the choice of a

project mission is endogenous and where the principal and the agent have misaligned mission

preferences, Cassar (2014) shows that it is optimal for the principal to (partly) compromise

on the choice of the mission in order to save on payments. Thus, in these theoretical models

monetary and non-monetary incentives are treated as substitutes by the employers. This leads

to a negative relationship between financial payments and the degree of mission-matching.

Furthermore, this may also result in a negative correlation between effort and incentive pay

in a cross section of organizations: organizations where the job missions are aligned with the

workers’ mission preferences may pay lower wage but may benefit from higher productivity

levels due to workers’ intrinsic motivation.

There are at least three reasons, however, why the assumptions of these models may be

violated and, in turn, why we may not observe employers offering the predicted contracts.

First, due to bounded rationality, some employers may simply fail to correctly anticipate the

effort premium resulting from the intrinsic motivation of workers. Second, some employers

may consider the mission of a project as a non-tradable characteristic, as it could be the case,

for instance, with some “moral” goods. As a consequence, they may be unwilling to make any

compromise on the mission.1 Third, and more importantly, fairness considerations may prevent

1

While empirical facts from the aid sector suggest that international organizations such as the UK’s Department of International Development, EuropeAid, and the World Bank, which are used to procure projects worth

millions of dollars, do in fact trade projects’ missions through the use of scoring auctions (Huysentruyt, 2011),

this may not hold true for smaller organizations or in a single employer-employee relationship. E.g. religious

schools may be unwilling to compromise on their dogma by allowing the teaching of science. Such “ideological”

issues can be very strong when charitable and social work is involved (Besley and Ghatak (1999, 2001)).

1

employers from offering a lower wage. It may, in fact, be considered unfair to take advantage

of workers’ intrinsic benefit from doing their job by lowering the wages. Fairness considerations

in the form of positive or negative expected reciprocity play a role, for instance, in Fehr et al.

(1993) and Fehr and Falk (1999). These studies show that, in markets with unemployment

and incomplete contracts, employers are unwilling to take advantage of workers’ underbidding

because of fear of triggering negative effort responses. Similarly, employers may be reluctant

to offer a lower wage due to other types of social preferences towards the workers. Employers

may be, for instance, inequity averse (Fehr and Schmidt, 1999), or, as conjectured by Gerhards

(2013), they may want to support the preferred mission of their workers by increasing their

wage.2

Given that job missions are particularly relevant in those organizations that are involved in

the provision of social goods and services, i.e. of those goods that have a positive externality in

society, such as aid, health, education, research, arts and so on, it is reasonable to hypothesize

that employers in such organizations may have similar fairness concerns and social preferences

as the one described above.

Whether these fairness considerations or social preferences are sufficiently strong to affect

employers’ design of contracts is an empirical question. To address this question I have conducted a laboratory labor market experiment in which pairs of subjects are matched to form a

principal-agent contractual relationship for the development of a social project. A laboratory

experiment is particularly suited to address these questions because it allows to control for

self-selection of workers with unobservable characteristics. While a negative wage differential

between the public and the private sector may be consistent with employers taking advantage

of public sector employees’ intrinsic motivation, this negative wage differential may also result

from workers with higher abilities self-selecting in the private sector, or from different production functions across sectors. A laboratory experiment allows to control for all these issues,

which could hardly be done otherwise.3

The design is as follows. The principal offers the agent a contract, which consists of a

mission4 and a wage, to carry out a project. The agent then chooses a monetary effort level

which generates a profit to the principal and a social output. The social output is implemented

2

The author finds that principals pay higher piece rates in contracts with the agents’ preferred mission than

in contracts with a random mission. However, given that in the design by Gerhards (2013) principals often

share the same mission preference as the agents, this may simply be the result of the employers wanting to elicit

more effort for their preferred mission than for a random mission.

3

A field experiment in this context is also very challenging because it would require the participation of

managers from different organizations. While this is not impossible, it is probably not the best approach for a

first study on this topic. Thus, this is left for future work.

4

A mission can be generally defined as the overall project’s design and characteristics: the type of good that

is provided, how it is provided, to whom it is provided, and so on.

2

as a donation to a charity, while the choice of the project mission is implemented as the choice

of which charity receives the donation. More specifically, the principal can offer two types of

contracts: an open contract or a closed contract. If the closed contract is offered, the effort

exerted by the agent generates a donation to the principal’s preferred charity. If the open

contract is offered, the effort exerted by the agent generates a donation to the agent’s preferred

charity.5 The agent is paid according to the wage (per-unit of effort) specified in the offered

contract. After receiving the contract, the agent chooses his effort level which determines

payoffs and donations. Thus, the employer cannot contract directly on effort. He can, however,

influence the agent’s effort level through the choice of the wage and through the choice of which

of the two types of contract to offer, namely, the mission.

Notice that the choice of the project mission is only relevant if it entails a trade-off for the

principal, namely, if the principal and the agent prefer different charities. If this wasn’t the

case, the choice between the open and the closed contract would be trivial and the question

whether the choice of the project mission is treated as substitute to monetary incentives could

not be addressed. Thus, to generate a pool of subjects who care about different charities, in

the recruitment process students were informed that they may earn slightly less than usual in

experiments but that they would be given the opportunity to generate a substantial donation

to their favorite charity. Furthermore, in order to sign up, subjects had to specify the name

and the link to the website of their favorite charity. This recruitment procedure turned out to

be successful as 92 different charities were chosen by 146 subjects.6

In order to identify how agents’ intrinsic motivation and mission preferences affects the

contracts offered by the principals, I need to compare these contracts with the contracts that

the principals would offer if the agents were not intrinsically motivated and, therefore, did not

care about the project mission. For this purpose, the experiment consisted of two treatments.

In the main treatment, the agents were allowed to choose any desired effort level for any given

wage. The parameters of the payoff functions were chosen such that an agent who is intrinsically

motivated and thus cares about the charity, would choose an effort level that is higher than the

wage offered in the contract. In the control treatment, the agents were not allowed to choose

more effort than the level that maximizes their monetary payoff. That is, they could not choose

an effort level that is higher than the wage specified in the contract. In this treatment any

effort premium from agents’ intrinsic motivation was, therefore, ruled out.

5

It is worth pointing out that differently from Fehr et al. (2013) and Charness et al. (2012), neither contracts

imply a delegation of decision from the principal to the agent. The decision is always made by the principal

between letting the agent exert effort for his preferred mission or not.

6

This recruitment procedure has, of course, generated a selected pool of subjects. This selection is, however,

necessary because the underlying theory is about employers and workers who care about the mission of the

project.

3

By comparing the wages and the frequency of open contracts being offered across the two

treatments, I am able to test if employers treat monetary incentives and the choice of the project

mission as substitutes to motivate effort provision. The main results are the following: (i) For

any given wage, effort levels in both types of contract are higher in the main treatment than

in the control treatment. Furthermore, within the main treatment, conditional on wage, effort

levels are higher in the open contract than in the closed contract. Thus, agents were motivated

to generate a donation under both contracts, but more so when the donation was made to their

preferred charity. This result shows that the mission of a job matters for motivated workers: the

higher the mission-matching, the higher the effort level. Moreover, the elicitation of principals’

beliefs suggests that the latter correctly anticipate this effort premium from agents’ intrinsic

motivation. (ii) Given a type of contract, open or closed, wages are lower in the main treatment

than in the control treatment. This suggests that the principals take advantage of the agents’

intrinsic motivation in Result i by offering lower wages. (iii) The open contract is offered more

frequently in the main treatment than in the control treatment. Thus, if faced with motivated

agents, principals are more willing to trade the job mission to save on monetary incentives.

Overall, these findings are consistent with the predictions of the standard contract theory

models. Result ii alone suggests that in a setting where the job mission is fixed, employers

take advantage of the workers’ intrinsic motivation by offering lower wages. Results ii and iii

together suggest that, in a setting where the job mission is endogenous and mission preferences

are misaligned, principals do treat the choice of the job mission as substitute to monetary

incentives in order to elicit effort from motivated agents.

Another fact worth pointing out is that the wage differential between treatments was found

to be the same in both types of contract. Based on the theoretical models, however, one could

have expected the difference in wages between the two treatments to be higher in the open

contract than in the closed contract. Indeed, given that agents’ intrinsic motivation is higher

under the open contract, the amount that a principal can save, in terms of wage, from being

matched with a motivated agent should be higher under the open contract than under the

closed contract. Why isn’t this the case? A potential explanation, emerging from the data,

is that many principals may be sacrificing financial savings in the open contract because they

are reluctant to offer a wage below what I call the standard wage, that is, the wage that a

principal would offer if neither him nor the agent cared about the charities. Such reluctance

seems related to fairness considerations: offering a wage below the standard wage is a clear

sign of taking advantage of workers’ intrinsic motivation, and therefore, many principals who

consider this to be unfair are more reluctant to lower the wage beyond that level.7

7

As it will be discussed later in the paper, these fairness considerations are, however, not linked specifically

4

Subjects’ responses to a survey conducted at the end of the experimental study are consistent

with this argument. When asked if, in the role of employers during a job interview, they would

offer a lower wage than the one they initially thought to offer if they realized that the job

candidate would really enjoy doing this job, only 22 subjects replied they would offer a lower

wage, while 124 subjects replied they would not offer a lower wage, most of them for fairness

reasons. By matching subjects’ survey responses with the decisions made in the experiment, I

find that in the main treatment, those 14 percent of principals who do not perceive as unfair

to offer a lower wage to the motivated job candidate are more likely in the open contract to

offer a wage below the standard wage compared to the other principals. Moreover, for this

small sub-sample of principals, the average offered wage in the open contract is lower than the

standard wage and the wage differential between treatments is higher in the open contract than

in the closed contract. Given the sub-sample small size, and given that the experiment was

not designed to test this specific hypothesis, this interpretation should be, however, taken with

caution.

So the overall picture that emerges from this study is that employers do take advantage of

worker’s intrinsic motivation by saving on wages, but only to the extent that the wages offered

are still considered fair. In other words, these fairness considerations are acting as a limited

liability constraint. Whether this constraint will be binding depends on what is considered to

be a fair wage in a specific natural environment. This is an empirical question which is certainly

worth addressing in future work.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The next section introduces the theoretical framework and predictions. Section II describes the experimental design. Section III

presents the results. Section IV discuss some results in more details. Section V concludes.

I. Theoretical Framework

I.1. The Model

The basis for my experimental design is an extension of the model by Besley and Ghatak (2005)

to an environment where the project’s mission is endogenous and where the principal and the

agent have different mission preferences. It can also be understood as an extension of the model

by Cassar (2014) to a context where output-contingent rewards are available.8

to reciprocity concerns or to inequity aversion.

8

Contrary to the model presented below, however, Cassar (2014) allows the project’s mission to be continuous

and the agents’ intrinsic motivation levels to be unobservable by the principal.

5

An agent is matched with a principal who offers him a contract for the development of

a social project. The contract specifies a wage w (per unit of effort) and a project’s mission

mi ∈ {mD , mA }, where mD is the preferred mission of the principal, mA is the preferred mission

of the agent, and mD 6= mA . The agent will then exert a level of effort, e, to develop the project.

The utility of the principal from implementing the contract (w, mi ) is equal to

V (e; w, mi ) = Π(e, w) + γmi D(e)

i = A, D

(1)

Π(e) is the profit generated by the project as a function of the agent’s effort. This is composed

of the monetary output minus the wage cost. γmi is the principal’s valuation for the social

output of a project with mission mi , and D(e) is the social output generated by the project as

a function of the agent’s effort. It follows that γmD > γmA ≥ 0, that is, the principal values

more the social output of a project with his preferred mission than with the preferred mission

of the agent. Finally, Π(.) and D(.) can be assumed to be linear in effort:

Π(e, w) = (π − w)e

(2)

D(e) = de

(3)

The principal chooses (w, mi ) that maximizes (1). Given the contract (w, mi ), the agent chooses

the level of effort that maximizes the following utility:

U (w, mi ; e) = we + αmi D(e) − C(e)

i = A, D

(4)

where αmi is the agent’s intrinsic motivation to develop a project with mission mi and C(e)

is the cost of exerting effort, which is equal to 21 e2 . It follows that αmA > αmD ≥ 0, that is,

the agent’s intrinsic motivation is higher when he works for his preferred mission than for the

preferred mission of the principal. If the agent were not motivated, he would not care about

the project mission, i.e. αmA = αmD = 0.9

I.2. Analysis and Theoretical Implications

For sake of notational clarity, let’s define wmi the wage paid to the agent if the project’s mission

mi is chosen. The agent’s optimal level of effort is then

e∗mi = wmi + αmi d

i = A, D

(5)

The agent’s optimal level of effort is increasing in the offered wage, in the intrinsic motivation

from working in a project with mission mi , αmi , and in the effort’s productivity in generating

9

Notice that in principle γmA and αmD could also be negative, that is, the principal and the agent could

derive an intrinsic cost from the social output of a project with mission mA and mD respectively. However, as

it will become clear from the results, there is little evidence of such preferences in the experiment.

6

social output, d. Since αmA > αmD , motivated agents exert more effort, for any given wage, in

contracts with their preferred mission. Furthermore, this level of effort is higher than the wage.

If an agent is not motivated, his optimal level of effort is equal to the wage independently of

the project mission.

Given the optimal level of effort in (5), the optimal wage in a contract with mission mi is

equal to

∗

wm

i

n

= Max 0 ;

1

[π

2

+ d(γmi

o

− αmi )]

i = A, D

(6)

The optimal wage is increasing in the effort’s productivity in generating profit π and in the

principal’s valuation of the social output of a project with mission mi , γmi . This is the preference

channel : everything else being equal, the more the principal cares about the social output of

a project, the higher the effort level he wants to elicit from the agent, and in turn, the higher

the wage he will offer in the contract. More importantly for this study, the optimal wage is

decreasing in the agent’s intrinsic motivation to work for a project with mission mi , αmi . This

is the saving channel : everything else being equal, the higher the agent’s intrinsic motivation,

the more the principal can save on monetary incentives, i.e., the more he can lower the wage.

The experiment is designed to identify this channel.

These two channels have three implications for contract design. First, since the preference

channel is stronger under the contract with the principal’s preferred mission (γmD > γmA ) while

the opposite holds true for the saving channel (αmA > αmD ), wages are higher in contracts

∗

∗

. This leads to a negative correlation

> wm

with the principal’s preferred mission, i.e. wm

A

D

between financial incentives and the alignment of the project mission with the agent’s mission

preferences. Second, because of the saving channel, motivated agents are offered lower wages

compared to non-motivated agents. If αmD > 0, this is true for both project missions. Third,

this wage differential should be higher if the motivated agent works for his preferred mission,

as the saving channel is stronger in this case. In other words, the principal can take more

advantage of the agent’s intrinsic motivation by lowering the wage when the latter works for

his preferred mission.

By replacing the optimal wage in the optimal effort function of the agent, I can derive the

optimal level of effort as a function of the exogenous parameters only:

e∗mi = 12 [π + d(γmi + αmi )]

i = A, D

(7)

Equation (7) suggests that for any project mission, the unconditional level of effort is increasing

in both the principal’s valuation for social output and the agent’s intrinsic motivation. Comparative statics depend on the specific values taken by γmi and αmi . Since these parameters

can take any value, I cannot predict whether the unconditional level of effort will be higher

7

under the contract with the principal’s preferred mission or under the contract with the agent’s

preferred mission. For sufficiently high αmA , however, it is clear that the level of effort will be

higher under the contract with the agent’s preferred mission. Since wages are lower under such

contracts, this can result in a negative correlation between effort and monetary incentive in a

cross-section of organizations.

Finally, I can derive the principal’s utility from each of the two contracts to make predictions

about the optimal choice of the project’s mission. Equation (1) can be rewritten as

∗

V (e∗ ; w∗ , mi ) = (π − wm

)e∗mi + γmi de∗mi

i

i = A, D

Replacing the optimal level of effort and the optimal wage gives

1

V (mi ) = [π + d(γmi + αmi )]2

4

i = A, D

(8)

As for the unconditional level of effort, the principal’s utility from the contract with project’s

mission mi is increasing in both the principal’s valuation for social output and the agent’s

intrinsic motivation for mission mi . Which project’s mission maximizes the principal’s utility

depends on the specific value taken by γmi and αmi , ∀ i = A, D. Notice, however, that if the

agent is not motivated, the principal is undoubtedly better off by choosing his preferred mission,

i.e. m∗i = mD . Indeed, if the principal cannot take advantage of the saving channel, there is no

reason why the principal should make a compromise on the mission. Therefore, compared to a

situation where the agent is not intrinsically motivated, if the agent is motivated the principal

should be more likely to offer the contract with the agent’s preferred mission.10

II. The Experiment

The design of the experiment closely follows the theoretical framework described in Section

I. Consistent with previous experimental studies, the social output generated by the project

is implemented as a donation to a charity that subjects can generate in addition to their

monetary payoffs. The choice of the project’s mission is implemented as the choice of which

charity receives the donation. My identification strategy of the causal effect of the agents’

intrinsic motivation on the choice of the wage and of the project mission is the comparison

between the contracts offered to motivated agents and the contracts the principal would offer

if the agents were not motivated. To do so, I run the two treatments described in Section II.3.

10

In a setting where mi is continuous, the model would predict that if the agent is intrinsically motivated,

the principal would always partly compromise the project mission (Cassar, 2014).

8

II.1. Recruitment

The implementation described above only works if subjects care about different charities. If this

were not the case, the choice of the project mission, i.e. the choice of which charity receives the

donation, would not entail any trade-off for the principal. Thus, the question whether the choice

of the project mission is treated as substitute to monetary incentives could not be addressed.

To generate such pool of subjects, in the recruitment process students were informed that they

may earn slightly less than usual in experiments but that they would be given the opportunity

to generate a substantial donation to their favorite charity. Furthermore, in order to sign up,

subjects had to specify the name and the website of their favorite charity. This recruitment

procedure turned out to be successful as 92 different charities were chosen by 146 subjects. As

soon as the subjects arrived in the laboratory, they received a list of all the charities that were

chosen by subjects participating in the same experimental session. The list also specified the

number of subjects choosing the same charity. Therefore, subjects knew the full distribution of

charities choices. In order to have updated information about subjects’ charities preferences,

at the beginning of the experiment subjects were asked to choose (again) their favorite charity

from the list.

II.2. Experimental design

After the instructions were read aloud, half of the subjects were assigned to the role of principals,

the other half the role of agents. The same role was kept throughout the experiment. Every

agent was then randomly matched to a principal. The experiment consisted of multiple periods.

At the beginning of each period, subjects were randomly and anonymously re-matched.

In each period the sequence of actions was as follows. The principal chose a wage w in the

integer set {1, 2, .., 9}, and whether to offer a closed or an open contract. If the closed contract

was offered, the effort exerted by the agent generated, in addition to the principal’s profit, a

donation to the principal’s preferred charity. If the open contract was offered, the effort exerted

by the agent generated, in addition to the principal’s profit, a donation to the agent’s preferred

charity. Thus, in terms of the model described in Section I, the closed contract corresponds to

the choice of a project mission equal to mD , while the open contract corresponds to the choice

of a project mission equal mA . The agent then chose a costly level of effort e in the integer set

{1, 2, .., 9} which determined payoffs and donations in that period. To rule out binding budget

constraints, at the beginning of each period every agent were endowed with 35 points. This

allowed the agent to exert the maximum level of effort even if the principal chose a wage of 1.

Both the principal’s profit and the level of donation depended linearly on effort as in (2) and

(3). Specifically, π = 10 and d = 20. This choice of parameters, along with the convex effort

9

function, made sure that it was not convenient neither for the principal nor for the agent to

maximize own income and donate later. Finally, at the beginning of each period a base income

of 20 points was given to every principal in order to get roughly the same monetary payoffs

under the optimal choices for agents and principals who did not care about charities, i.e. for

e = w = 5 in both contracts.

As subjects may vary in the extent to which they care about the charities and this is not

observable, the strategy method was used to elicit the principal’s choice of wage and the agent’s

choice of effort for both the closed and open contract. More specifically, I elicited the agent’s

effort choice for each possible wage in each contract. To elicit the principal’s beliefs about the

agent’s effort, the principal also specified an expected level of effort for each of the two contracts

given the chosen wage. This elicitation was, however, not incentivized and the expected effort

level was not revealed to the agent. The principal would then choose which contract, between

the open and the closed, to offer to the agent. The chosen contract was implemented with 75%

probability, whereas with 25% probability the other contract was implemented. This random

implementation of contracts was necessary to make the choice of wage incentive compatible even

in the principal’s least preferred contract. Furthermore, as agents did not know with certainty

whether the implemented contract corresponded to the contract chosen by the principal, this

random implementation, together with the strategy method for the elicitation of the agents’

effort in each contract, had the advantage to rule out potential agents’ reciprocity towards

principals who chose to offer the open contract.11 At the end of each period, payoffs realized and

became observable to the principal and the agent. To improve learning, the principal observed

not only the level of effort and the donation realized, but also the level of effort chosen by the

agent in the contract that was not implemented. Similarly, the agent observed not only the

wage offered in the implemented contract, but also the wage offered in the remaining contract.

He also observed which of the two contracts the principal had chosen to offer.

It is important to point out that neither the principals nor the agents were revealed the

preferred charity of the subject they were matched with. It follows that the principal’s choice

between the closed and the open contract was equivalent to a choice between a contract that

generated a donation to his preferred mission with certainty and a contract that generates

a donation to any of the charity specified in the list with some probability.12 Similarly, an

11

Reciprocity towards the choice of the mission would have, indeed, the same implications as an increase

in αmA , so it could have acted as a potential confound. On the contrary, reciprocity towards high wages

would reduce the principal’s benefit from saving on monetary incentives and, therefore, work against my main

hypothesis. Finally, reciprocity only towards high wages in the open contract could lead to the opposite

prediction regarding the optimal choice of wages, namely, the principal might want to set higher wages in the

open contract than in the closed contract.

12

This probability was known to the subjects because, as mentioned above, they knew the full distribution of

charities choices.

10

agent knew that his effort level in the closed contract would generate a donation to any charity

specified in the list with a given probability, whereas his effort level in the open contract would

generate a donation to his preferred charity with certainty. Thus, everything else being equal,

it is clear that the principal’s valuation of social output was higher under the closed contract

while the agent’s motivation was higher under the open contract. Theoretical predictions were

therefore unchanged.

While this design feature did not affect the theoretical predictions, it had two main advantages. First, this design avoided the risk, ex-ante, of having too many pairs of principal-agent

preferring the same charity. Second, it eliminated any heterogeneity across periods and treatments in the agent’s intrinsic motivation under the closed contract and in the principal’s valuation of output in the open contract. In terms of the model, this was equivalent to keeping αmD

and γmA of each individual constant across periods and treatments. Indeed, such unobservable

heterogeneity across periods and treatments could have added substantial noise to the data and

acted as a potential confound.

II.3. Treatments

The experiment involved two treatments. Each subject participated in both treatments. In the

main treatment the agent was free to choose any desired level of effort. As shown in equation

(5), if the agent cared about the charity he would choose an effort level that is higher than the

wage offered in the contract. In the control treatment, the agent was not allow to exert more

effort than the level which maximized his material payoff. That is, the level of effort could not

be higher than the wage specified in the contract. In this treatment any effort premium from

agents’ intrinsic motivation was, therefore, ruled out.

To keep the notation consistent with the theory described in Section I, let wmA and emA

be, respectively, the wage and the effort level chosen in the open contract, while let wmD and

emD be, respectively, the wage and the effort level chosen in the closed contract. Treatment

variations are summarized in Table I.

Table I: Treatment variation

Treatment

Main

Control

emA

Effort

∈ {1, 2.., 9} ; emD ∈ {1, 2.., 9}

emA ≤ wmA ; emD ≤ wmD

To make sure that both the principals and the agents understood the trade-off into play, a

payoff table was given in the instructions where, in red, was the effort choice that maximizes

11

the agent’s income for any given wage - thus, the table diagonal was in red - and, in blue, was

the effort choice that maximizes the donation for any given wage, i.e. an effort level of 9 for

any given wage. Thus, based on this payoff table, it was clear to both the principals and the

agents that if the latter cared about the charity, in the main treatment they would choose a

higher effort level than the wage.

Six sessions were run in total. To control for potential order effects, the order in which

the two treatments were played were systematically modified across sessions. Each treatment

lasted 10 periods. So overall, every subject made decisions for 20 periods. Payments to subjects

and donations to charities were made according to the outcome of one out of the 20 periods

selected at random.

II.4. Hypotheses

The analysis of the theoretical model in Section I generates a whole set of predictions which I

now restate as hypotheses to be tested in the experiment.

First, the model predicts that conditional on wage, motivated agents exert more effort than

non-motivated agents, particularly so in contracts with their preferred mission. This translates

to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 Conditional on wage, effort is higher in the main treatment than in the control

treatment, particularly so in the open contract.

This first hypothesis tests if the project mission is effective in motivating effort provision. Notice

that this hypothesis needs to be satisfied in order to test the remaining hypotheses.

Next, conditional on the hypothesis above being satisfied, the model makes predictions

about the level of wage offered by principals. Specifically, it predicts that wages are higher in

contracts with the principals’ preferred mission. Indeed, in such contracts, there is (1) a stronger

preference channel: the principal wants to elicit a higher donation for his preferred charity than

for any other charity; (2) a weaker saving channel: the agent needs higher monetary incentives

to provide effort for the principals’ preferred charity than for his own preferred charity. This

translates to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 Wages are higher in the closed contract than in the open contract.

This second hypothesis tests if, contrary to the results in Gerhards (2013), there is a negative

correlation between financial incentives and the alignment of the project mission with the

agents’ mission preferences. Testing this hypothesis alone, however, does not answer the first

12

main question of this paper, namely, if the principal takes advantage of the agent’s intrinsic

motivation by saving on monetary incentives. To address this question, I need to disentangle the

saving channel from the preference channel. My identification strategy is to compare the wage

offered by principals within a specific type contract across the two treatments. By comparing

wages within the same type of contract, the preference channel is constant, and therefore, any

observed wage differential across treatments must come from the saving channel: while the

saving channel should be active in the main treatment, in the control treatment, since the

effort premium from intrinsic motivation is ruled out by design, the saving channel is switched

off.

Hypothesis 3 Conditional on the type of contract, wages are lower in the main treatment than

in the control treatment.

This hypothesis tests if, given a certain project mission, the principal takes advantage of the

agent’s intrinsic motivation to work for that mission by lowering the wage. In other words, this

tests if the principal would pay a motivated agent a lower wage than a non-motivated agent.

The size of the saving channel will depend, of course, on the size of the effort premium resulting from the agent’s intrinsic motivation in Hypothesis 1. Since I expect the effort premium

to be higher if the agent works for his preferred mission, the next hypothesis follows:

Hypothesis 4 The wage differential across treatments is higher in the open contract than in

the closed contract.

Finally, the model makes predictions about the principal’s choice of the project’s mission.

More specifically, if the agent is not motivated, the principal has no reason to choose a different

mission from his preferred one. On the contrary, if the agent is motivated, the principal may

want to compromise on the mission in order to save on monetary incentives. The next hypothesis

follows:

Hypothesis 5 The principal is more likely to offer the open contract in the main treatment

than in the control treatment.

Hypotheses 3-5 together test if the principal treat the choice of the project mission as a substitute for monetary incentives in motivating effort provision.

II.5. Elicitation of Preferences over Charities

It is important to point out that subjects are likely to have heterogenous preferences over the

charities. In terms of the model, this means that the agent’s parameters αmA and αmD and

13

the principal’s parameters γmD and γmA are individual specific. Therefore, to add control and

run robustness checks, it is useful to get an independent measure of these parameters at an

individual level.

For this purpose, I use an allocation game with concave allocation function. At the end of

the experiment, subjects are asked to allocate 40 points between themselves, their preferred

charity, and the preferred charity in the list of a participant taken at random. Points are

√

allocated according to the following allocation function Pj = 7 ∗ pj , where j identifies who

receives the points between the subject, his/her preferred charity, and a random charity in the

list. So in words, Pj are the points that j gets if pj points are subtracted from the 40 points in

P

favor to j. All 40 points have to be allocated, which means that j pj = 40.

According to this allocation function, any subject who cares about his preferred charity, i.e.

any agent with αmA > 0 or any principal with γmD > 0, should allocate some points to his/her

preferred charity. The optimal number of points allocated to the preferred charity is increasing

in αmA , or equivalently in γmD . Similarly, any subject who cares about the charities in the list

as a whole, i.e. any agent with αmD > 0 or any principal with γmA > 0, should allocate some

points to the random charity. The optimal number of points allocated to the random charity

is increasing in αmD for the agents, or equivalently in γmA for the principals.

The advantage of using an allocation game with concave allocation function is that it rules

out potential corner solutions that may arise from efficiency concerns. So this method generates

an approximate measure at an individual level of (i) the intensity with which subjects care

about their preferred charities, i.e. of the size of αmA and γmD ; (ii) the importance of subjects’

preferred mission compared to other missions, i.e. αmA − αmD and γmD − γmA . The latter

measures to what extent a principal or an agent is mission-driven and it is particularly relevant

for comparative statics across types of contract.

Finally, in a short questionnaire run at the end of the experiment subjects were asked, for

each of the charity in the list, the following question: “From 0 to 10 how much do you stand

behind the objectives of the following charity?”

II.6. Procedural details

Overall 146 subjects participated in the experiment, 73 in the role of principals and 73 in

the role of agents. All six sessions were conducted in November 2013. The experiment was

programmed and conducted with the software z-Tree (Fischbacher, 2007). Our subject pool

consisted primarily of students at the University of Zurich and at the Federal Institute of

Technology in Zurich and were recruited using the software hroot (Bock et al., 2012). Subjects

were paid based on the number of points generated in one period selected at random from the

14

experiment and based on the number of points they allocated to themselves in the allocation

game. Donations to charities were also made accordingly. In addition, each subject received a

show-up fee of 10 SFr. On average, an experimental session lasted 1 hour and 45 minutes. The

average payment was 35 SFr and the average donation was 36 SFr per pair of subjects.

III. Results

III.1. Agents’ effort choices

I start by analyzing the agents’ effort choices for different wages and contracts in the two

treatments. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, I find:

Result 1 For any given wage, effort is higher in the main treatment than in the control treatment, particularly so in the open contract.

Evidence for Result 1 can be seen in Figure I. This figure shows the effort choices per wage

and type of contract elicited through the strategy method in each treatment. The black line

represents the 45 degrees line. Thus, any point on the RHS of the black line corresponds to

a (positive) effort premium from intrinsic motivation. As predicted, because of the imposed

restriction on the agents’ choice set, in the control treatment the average effort in both contracts

is equal or slightly lower than the wage. On the contrary, in the main treatment average effort

in both contracts is always higher than the wage - with the obvious exception for a wage equal

to 9. In particular for the open contract, the effort premium is approximately equal to one unit

for any given wage, i.e. for a wage of 3, the average effort is equal to 4, and so on.

To assess the statistical significance of these effort differences across treatments, I use a

one-sided clustered version of the signed-rank test proposed by Datta and Satten (2008), which

controls for potential dependencies between observations. Recall that the game was repeated 10

times (periods) per treatment. That is, for each individual, type of contract, and wage, I elicit

10 effort choices in each treatment. Keeping the type of contract fixed, for each individual and

period I then calculate the difference between the effort choice in the main treatment and in

the control treatment for any given wage. This generates 10 observations per subject per wage

within a specific type of contract. Clustering at the individual level, I find that for any wage

level in a specific type of contract, the effort choice in the main treatment is significantly higher

than the effort choice in the control treatment - and also higher than the wage (p < 0.01). This

holds for both the open and the closed contract.

15

Control Treatment

wage

9

9

8

8

7

7

6

6

5

5

4

4

3

3

2

2

1

1

1

2

3

4

5

6

average effort

closed contract

Main Treatment

wage

7

8

9

1

open contract

2

3

4

5

6

average effort

closed contract

7

8

9

open contract

Figure I: Effort Choices

It can be seen, furthermore, that within the main treatment, for any given wage average

effort is higher in the open contract than in the closed contract. Again, to assess the statistical

significance of all these effort differences, I use the one-sided clustered version of the signedrank test proposed by Datta and Satten (2008). Focusing on the main treatment only, for each

individual and period I calculate the difference between the effort choice in the open contract

and in the closed contract for any given wage. This generates 10 observations per subject, per

wage. Clustering at the individual level, I find that for any wage level, the effort choice in the

open contract is significantly higher than in the closed contract (p < 0.01).13

Similar results are found by running OLS regressions, which are reported in Table II. It

can been seen from regression (1) that conditional on wage, average effort is 0.51 percentage

points significantly higher in the main treatment than in the control treatment. Furthermore,

as shown in the interaction of main treatment and open contract, this treatment difference is

0.42 percentage points significantly higher in the open contract than in the closed contract.

Thus, the overall effort premium from being matched with a motivated agent who work for his

preferred mission is approximately one additional unit of effort.14 Compared to regression (1),

13

The same results, including the treatment effect described above, hold if I cluster at the session level.

Note that if subjects in the control treatment were really non-motivated, the coefficient on the variable open

contract should not be significant, as they would not care about any charity. So probably in the experiment a

14

16

Table II: Effort levels

(1)

FE

0.942***

(0.014)

0.510***

(0.109)

0.179***

(0.046)

0.422***

(0.083)

–0.014

(0.008)

wage

main treatment

open contract

main*open

wage*open

mission driven (αmA > αmD )

mission driven*main*open

constant

0.041

(0.088)

Yes

No

Yes

0.878

26280

Round FE?

Session FE?

Individual FE?

Adj. R2

Observations

(2)

RE

0.942***

(0.014)

0.510***

(0.109)

0.179***

(0.046)

–0.157

(0.148)

–0.014

(0.008)

0.142

(0.153)

0.813***

(0.207)

–0.017

(0.131)

Yes

Yes

No

0.881

26280

Standard errors are clustered at the individual level. Regression (1) uses a fixed-effect model, whereas regression

(2) uses a random-effect model. In regression (2), “mission driven” is a dummy variable that takes value equal 1

if, in the allocation game, the agent has allocated more points to his preferred charity than to a random charity

in the list, and 0 otherwise. Significance levels: *** p<.01, ** p<.05, * p<.1.

regression (2) uses data from the allocation game to distinguish between agents with different

charity preferences. More specifically, in the main treatment the effort premium from the open

contract should increase in how much an agent cares about his favorite charity compared to any

other charity in the list. In terms of the model, this means that the effect should be increasing

in αmA − αmD . A proxy for this variable is given by the difference between the number of

points allocated to one’s preferred charity and the number of points allocated to one random

charity in the list in the allocation game. I therefore distinguish between those agents whom I

define as mission driven, i.e. those who allocated more points to their preferred charity than

to the random charity, and those who allocated the same number of points, including 0, to

their preferred charity and to the random charity. As shown in regression (2), the interaction

of main treatment, open contract and mission driven agents is highly significant and explains

the overall effort premium from the open contract in the main treatment - the interaction of

minority of workers disliked the charities of the principals, and thus, in the control treatment they exerted a

lower effort than in the open contract. This, however, does not affect the theoretical predictions.

17

main treatment and open contract is no longer significant. Results are robust to using a Tobit

model, to clustering at the session level, or to restricting attention to the first period only, i.e.,

where potential spillover effects are fully ruled out.

So, all together, these results show that agents were motivated to generate a donation to a

charity, but more so if the donation was directed to their preferred charity rather than to the

preferred charity of the principal.

III.2. Principals’ beliefs

Control Treatment

Main Treatment

wage

wage

9

9

8

8

7

7

6

6

5

5

4

4

3

3

2

2

1

1

1

2

3

4

5

6

average effort belief

closed contract

7

8

9

1

2

open contract

3

4

5

6

average effort belief

closed contract

7

8

9

open contract

Figure II: Beliefs about Effort

An equivalent important question is whether principals anticipated this effort premium from

agents’ intrinsic motivation. If this were not the case, it would not make sense to ask if principals

take advantage of it by lowering the wages. Therefore, I analyse the principals’ beliefs about

the agents’ effort, given the wage they choose to offer in each type of contract. Recall that for

each treatment and type of contract, I elicited 10 principals’ beliefs about agents’ effort, one

for every offered wage. Figure II shows the average effort expected by principals for a given

chosen wage.

Consistent with the actual agents’ effort choices described in Figure I, in the control treatment the average effort level expected by the principals is equal or slightly lower than the wage

18

in each type of contract.15 On the contrary, in the main treatment principals expect an effort

level that is higher than the wage offered in the contract, particularly so in the open contract.

By comparing with the actual agents’ effort choices, it can be seen that for wages below 4,

principals actually over-estimate the agents’ effort premium.

Table III: Beliefs about effort

wage

main treatment

open contract

main*open

wage*open

constant

Round FE?

Session FE?

Individual FE?

Adj. R2

Observations

(1)

FE

0.686***

(0.050)

0.309***

(0.091)

0.137

(0.224)

0.703***

(0.118)

–0.053

(0.035)

1.520***

(0.299)

Yes

No

Yes

0.468

2920

Standard errors are clustered at the individual level. Significance levels: *** p<.01, ** p<.05, * p<.1.

Similar results are found by running an OLS regression, which is reported in Table III. It can

been seen that conditional on wage, average expected effort is 0.3 percentage points significantly

higher in the main treatment than in the control treatment. Furthermore, as suggested by the

coefficient of the interaction term, this treatment difference is 0.7 percentage point significantly

higher in the open contract than in the closed contract. So, consistent with the actual agents’

effort choices, the overall expected effort premium from being matched with a motivated agent

who work for his preferred mission is approximately one additional unit of effort.16 Again,

results are robust to using a Tobit model, to clustering at the session level, or to restricting

attention to the first period only where potential spillover effects are fully ruled out.

Overall, these results suggest that principals correctly anticipate that agents’ are intrinsically

motivated to generate a donation to a charity, particularly so in the open contract.

15

For wages below 5, however, this result should be taken with extreme caution because there are very few

observations. Indeed, based on equation (6), in the control treatment principals should not offer wages below 5.

16

Note that here the variable open contract is not significant, so in the control treatment principals do not

expect any difference in effort between the open or closed contract.

19

III.3. Principals’ wage choices

I now analyze the wage offered by principals in different contracts and treatments. Consistent

with Hypothesis 2 I find that:

Result 2 Wages are higher in the closed contract than in the open contract

6

Average wage

4

5

6

5

4

Average wage

7

Closed Contract

7

Open Contract

Control treatment

Main treatment

Control treatment

Main treatment

Figure III: Wage choices

Evidence for Result 2 can be seen in Figure III. This figure compares the average wage

offered across treatments and contracts. It can be seen that in both treatments, the average

wage in the closed contract is approximately 0.75 percentage points (or 14 percent) higher

than in the open contract. To test the significance of this difference, I use again a one-sided

clustered version of the signed-rank test proposed by Datta and Satten (2008), which controls

for potential dependencies between observations. For each individual and period, I calculate the

difference between the wage offered in the closed contract and in the open contract. Clustering

at the individual level, I find that this difference is highly significant (p < 0.01). This result

confirms the negative relationship between financial incentives and the alignment of the project

mission with the agents’ mission preferences.

Figure III also reveals the first main result of this paper. Consistent with Hypothesis 3, I

find:

Result 3 For each type of contract, wages are lower in the main treatment than in the control

treatment.

It can be seen that for each type of contract, the average wage in the control treatment is

approximately 0.7 percentage points (or 14 percent) higher than in the main treatment. To

20

test the significance of these differences, I use again the one-sided clustered version of the

signed-rank test proposed by Datta and Satten (2008). Keeping the type of contract fixed, for

each individual and period, I calculated the difference between the wage offered in the control

treatment and in the main treatment. Clustering at the individual level, I find that these

differences are highly significant (p < 0.01) in both the open contract and the closed contract.17

Thus, this result shows that principals take advantage of agents’ intrinsic motivation by lowering

the wage by approximately 14 percent.

Finally, Figure III reveals another important fact: the wage differential between treatments

is the same in both types of contract. This is confirmed by non-parametric statistical tests. So

in others words, in contrast with the theoretical predictions, the saving channel is not higher

in the open contract than in the closed contract. Hypothesis 4 is, therefore, rejected.

Result 4 There is no difference in the wage differential between treatments across the two

contracts.

Similar results are found by running OLS regressions, which are reported in Table IV. It

can be seen from regression (1) that wages in the open contract are 0.76 percentage point lower

than in the closed contract. This effect should be higher the stronger is the preference channel

in the closed contract compared to the open contract, that is, the more a principal cares about

his favorite charity compared to any other charity in the list. In terms of the model, it means

that the effect should be increasing in γmD − γmA . A proxy for this variable is given by the

difference between the number of points allocated to one’s preferred charity and the number of

points allocated to one random charity in the list in the allocation game. I therefore distinguish

between those mission-driven principals who allocated more points to their preferred charity

than to the random charity, and those who allocated the same number of points, including 0, to

their preferred charity and to the random charity. As shown in regression (2), the interaction of

open contract and mission driven principals is negatively significant and explains a large part

of the overall wage differential between the open and the closed contract.

Furthermore, it can be seen that wages in the main treatment are 0.68 percentage point lower

than in the control treatment. This difference is highly significant. The interaction between

open contract and main treatment is, however, positive and insignificant. This confirms that

the treatment effect is the same in both contracts. Explanations for this result are discussed in

Section IV. Again, results are robust to using a Tobit model, to clustering at the session level,

or to restricting attention to the first period only where potential spillover effects are fully ruled

17

The same results, including the wage difference between contracts described above, hold if I cluster at the

session level.

21

out.18

Table IV: Wage choices

(1)

FE

–0.755***

(0.156)

–0.684***

(0.131)

0.056

(0.149)

open contract

main treatment

main*open

mission driven (γmD > γmA )

mission driven*open

constant

6.041***

(0.152)

Yes

No

Yes

0.125

2920

Round FE?

Session FE?

Individual FE?

Adj. R2

Observations

(2)

RE

–0.392***

(0.129)

–0.684***

(0.131)

0.056

(0.149)

0.479

(0.301)

–0.520**

(0.217)

6.003***

(0.414)

Yes

Yes

No

0.096

2920

Standard errors are clustered at the individual level. Regression (1) uses a fixed-effect model, whereas regression

(2) uses a random-effect model. In regression (2), “mission driven” is a dummy variable that takes value equal

1 if, in the allocation game, the principal has allocated more points to his preferred charity than to a random

charity in the list, and 0 otherwise. Significance levels: *** p<.01, ** p<.05, * p<.1.

III.4. Principals’ contract choices

Next, I analyze the principals’ contract choices across treatments. Consistent with Hypothesis

5, I find:

Result 5 The open contract is more frequently offered in the main treatment than in the control

treatment.

Evidence for Result 5 can be see in Figure IV. In the main treatment the open contract

is offered approximately 40 percent of the times, whereas in the control treatment the open

contract is offered approximately 28 percent of the times.19 To assess the statistical significance

18

Figure A.1 in the Appendix also reports the time path of the wage offered in the open and in the closed

contracts across treatments. It can be seen that throughout all time periods, for both types of contracts, wages

are higher in the main treatment than in the control treatment. Furthermore, within each treatment, wages are

higher in the closed contract than in the open contract.

19

Notice that based on the predictions from standard contract theory models, the principal should never offer

the open contract in the control treatment. Indeed, as any effort premium is ruled out by design, there is no

reason to offer the open contract in the control treatment. Thus, this result is probably driven by some of social

preferences of the principals towards the agents.

22

.4

.3

.2

.1

0

Percentage of open contracts

.5

Choice Open Contract

Control treatment

Main treatment

Figure IV: Contract choices

of this difference, I use again the one-sided clustered version of the signed-rank test proposed

by Datta and Satten (2008). For each individual and period, I calculate the difference between

the type of contract offered in the main treatment and in the control treatment. Clustering at

the individual level, I find that this difference is highly significant (p < 0.01).20

Additional evidence for Result 5 can be found in the OLS regressions reported in Table

V. It can be seen that the probability of the open contract being offered is approximately 12

percent higher in the main treatment than in the control treatment. According to regression

(2), however, this effect is not larger for mission driven principals. The results are robust to

using a Probit model and to clustering at the session level.21

Results 3 and 5 together provide evidence that principals treat the choice of the project

mission as substitute for monetary incentives. Motivated agents are more likely to work for

their preferred missions and are paid less. This answers the second main question of the paper.

III.5. Realized effort, wage and profit

I now turn my attention to the realized effort and wage choices. As it can be seen in Figure

A.3, the average realized effort is approximately equal to 6 in both treatments. This means

that, on average, the same amount of donation was generated across treatments. However, as

20

The same results are found if I cluster at the session level.

Figure A.2 in the Appendix also reports the time path of the contract choice across treatments. It can be

seen that, with the exception of the first period, the frequency of open contracts being offered is always higher

in the main treatment than in the control treatment.

21

23

Table V: Choice open contract

(1)

FE

0.116***

(0.029)

main treatment

mission driven

mission driven*main (γmD > γmA )

constant

0.298***

(0.042)

Yes

No

Yes

0.024

1460

Round FE?

Session FE?

Individual FE?

Adj. R2

Observations

(2)

RE

0.132**

(0.055)

–0.069

(0.085)

–0.022

(0.065)

0.331***

(0.104)

Yes

Yes

No

0.024

1460

Standard errors are clustered at the individual level. Regression (1) uses a fixed-effect model, whereas regression

(2) uses a random-effect model. In regression (2), “mission driven” is a dummy variable that takes value equal

1 if, in the allocation game, the principal has allocated more points to his preferred charity than to a random

charity in the list, and 0 otherwise. Significance levels: *** p<.01, ** p<.05, * p<.1.

it also appears in Figure A.3, the average realized wage is approximately 0.6 percentage points

(10 percent) lower in the main treatment than in the control treatment. Thus, in the main

treatment, principals were able to induce the same level of effort as in the control treatment

but for a lower wage. As it can be seen in Figure A.4, these financial savings from agents’

intrinsic motivation increases principals’ average profit in the main treatment by approximately

4 percentage point (10 percent) compared to the control treatment. On the contrary, agents’

average income is approximately 5 percentage point (9 percent) lower in the main treatment

than in the control treatment.

IV. Discussion

In this section, I discuss potential explanations for Result 4, that is, for why the wage differential

between treatments is not higher in the open contract than in the closed contract. Indeed, given

that agents’ intrinsic motivation is higher under the open contract, the amount that a principal

can save in terms of wage from being matched with a motivated agent should be higher under

the open contract than under the closed contract. Why isn’t this the case?

Based on Figure II and Table III, this does not seem to depend on principals’ erroneous

beliefs about agents’ intrinsic motivation, as the formers correctly anticipate a higher effort

24

premium in the open contract than in the closed contract for any given wage.

A potential explanation, consistent with the data, is that many principals may be sacrificing

financial savings in the open contract because they are reluctant to offer a wage below what

I call the standard wage, that is, the wage that a principal would offer if neither him nor the

agent cared about the charities, namely, if γmi = αmi = 0, i ∈ {A, D}. Given the parameters

chosen in the experiment, this corresponds to a wage of 5. Notice, that based on equation

(6), in the main treatment the wage offered by the principals in the open contract should be,

on average, lower than the standard wage. Indeed, unless principals care systematically more

about all charities than agents - which, in the experiment, is ruled out by randomization- αmA

should be, on average, higher that γmA , and therefore, in the main treatment the average wage

in the open contract should be lower than 5.22 Importantly, as it is evident from equation (6),

the same predictions do not hold for the closed contract. The reason is that in such contracts

principals are more motivated than the agents to generate a donation, as the latter is made to

their preferred charity. That is, γmD should be, on average, higher that αmD .23 Similarly, since

in the control treatment the saving channel is switched off, the wage should never be lower than

5 in neither type of contracts. Thus, if, as I hypothesize, such standard wage fairness constraint

exists, it would only be binding for the open contract in the main treatment, but not in the

closed contract nor in the control treatment.

Consistent with this argument, as shown in Figure III, in the control treatment or in the

closed contract, the average wage is significantly higher than 5, whereas in the open contract

in the main treatment the average wage is just equal to 5. A similar picture emerge if we look

at the distribution of wages chosen in different treatments and contracts (Figure A.5). While

the frequency of wages below 5 in the open contract in the main treatment (30 percent) is

significantly higher than in the closed contract (17 percent) or than in the control treatment

(11 percent), it is still quite low compared to the theoretical predictions. From there, my

conjecture that principals are reluctant to set a wage below the standard wage.

Taking this conjecture as given, the next question is why are the principals reluctant to set

a wage below the standard wage. Inequity aversion as defined in Fehr and Schmidt (1999) does

not seem to be the reason because, given the parameters chosen in the experiment, inequity

averse principals would prefer wages that are equal or lower than the standard wage, but not

higher. Neither is there evidence, from Figure I or Figure II, of negative reciprocity nor of

22

This is confirmed by the data from the allocation game. On average, agents allocate to their preferred

charity more than twice (10 points) as much as the principals allocate to a random charity in the list (4.3

points).

23

This also is confirmed by the data from the allocation game. On average, principals allocate to their

preferred charity almost 3 times (11.7 points) as much as the agents allocate to a random charity in the list (4

points).

25

expected negative reciprocity by principals with respect to wages below the standard wage in

the open contract.24

Such reluctance seems related to a different type of fairness considerations: offering a wage

below the standard wage is a clear sign of taking advantage of workers’ intrinsic motivation, and

therefore, many principals who consider this to be unfair are more reluctant to lower the wage

beyond that level. Subjects’ responses to a survey conducted at the end of the experimental

study are consistent with this argument. When asked if, in the role of employers during a job

interview, they would offer a lower wage than the one they initially thought to offer if they

realized that the job candidate would really enjoy doing this job, only 22 subjects replied they

would offer a lower wage, while 124 subjects replied they would not offer a lower wage, most of

them for fairness reasons.

By matching subjects’ survey responses with the decisions made in the experiment I get

the following results. Regressions reported in Table A.1 show that in the main treatment those

14 percent of principals who do not perceive as unfair to offer a lower wage to the motivated

job candidate are more likely in the open contract - but not in the closed contract- to offer

a wage below the standard wage compared to the other principals (p < 0.1). This difference

is equally significant using a clustered version of the Rank-Sum test proposed by Datta and

Satten (2005). Furthermore, for this sub-sample of principals, Figure A.6 shows that: (i) In the

main treatment, throughout all times periods, the average wage offered in the open contract

is lower than the standard wage. (ii) In almost every period, the wage differential between

treatments is higher in the open contract than in the closed contract.25 Given the sub-sample

small size, and given that the experiment was not designed to test this specific hypothesis, this

interpretation should be, however, taken with caution.

So the overall picture that emerges from this analysis is that principals do take advantage

of agents’ intrinsic motivation by saving on wages, but only to the extent that the wages offered

are still considered fair. In this experiment, principals seemed to be willing to take advantage

of agents’ intrinsic motivation as long as the offered wage was still higher or equal than the

standard wage. Contrary to the theoretical predictions, only one third of the principals were

willing to offer a motivated agent a wage below the standard wage in the open contract. Thus,

these fairness considerations seem to act as a limited liability constraint. This constraint makes

the substitution between monetary and non-monetary incentives imperfect.

24

Given a wage below the standard wage, only 8% of the observed effort levels are lower than the wage offered

in the open contract.

25

However, potentially due to the lack of power in such a small sample, I cannot establish statistical significance.

26

V. Concluding Remarks

Recently, much attention has been devoted to study how agents respond to different monetary

and non-monetary incentives.26 There is much less evidence, however, on whether principals

write contracts with these responses in mind. This paper reports the results from an experiment

that was designed to test, for the first time, how principals write contracts when agents care

about the mission of their job and when the principals have two instruments, the wage and the

choice of the project mission, to influence the agents’ effort.

On the whole, my results provide evidence for the validity of the theoretical predictions

from standard contract theory models with motivated agents. I show that principals take

advantage of agents’ intrinsic motivation by lowering the wage and use the choice of the project

mission as a substitute for monetary incentives. Because of fairness considerations, however,

this substitution remains imperfect.

But, of course, some questions remain open. First, the experiment is designed to test

the validity of such predictions in a fully “neutral” environment, namely, in the absence of

additional features of labor relations that may play a role in a natural environment. In reality,

the matching of employers and workers is not exogenous, but rather, workers and employers

with similar mission preferences will try to match and form a long-term contractual relationship.

This selection and long-term interaction may, of course, enhance the development of social ties

between the employers and the workers and, in turn, increase the effect of fairness considerations

relative to a one-shot game. Whether these stronger fairness considerations would translate into

higher wages or into better alignments of the job mission with the workers’ preferred mission

remains, however, an open question.

Finally, while the experiment did not allow for any competitive forces, in a natural environment competition between workers plays a crucial role in the determination of wages.

More specifically, competition is likely to act against fairness considerations and reinforce the

substitutability between monetary and non-monetary incentives: why should a non-profit organization hire a new employee if it can count on the effort of a motivated volunteer who is

willing to work for free? This and other extensions are left for future work.

26

These incentives include not only the job mission, but also status incentives and social recognition (Kosfeld