Comparative Historical Analysis: Some Insights from Political Transitions of

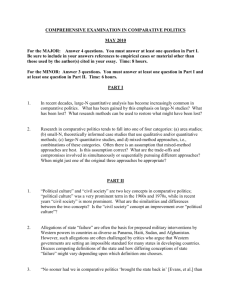

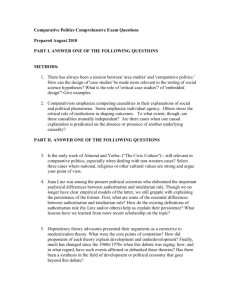

advertisement