THE RE-ENGINEERED NEW DEAL 25 PLUS:

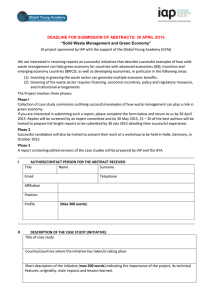

advertisement