Employers Skill Survey New Analyses and Lessons Learned

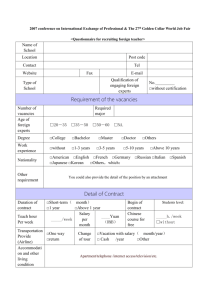

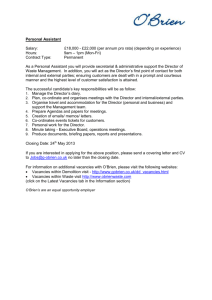

advertisement