Exploring Local Areas, Skills and Unemployment The Relationship Between Vacancies and

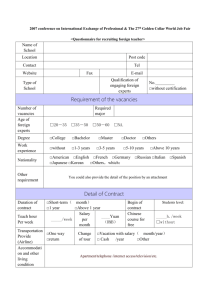

advertisement