EdPolicyWorks Working Paper: Socioeconomic Gaps in Early Childhood Experiences, 1998 to 2010

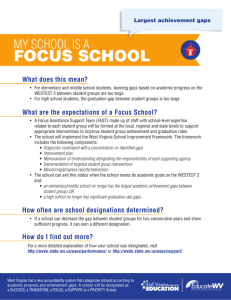

advertisement