Document 12295229

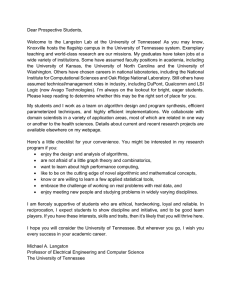

advertisement