SOCRATES Grundvig Project An overview of the different National Contexts

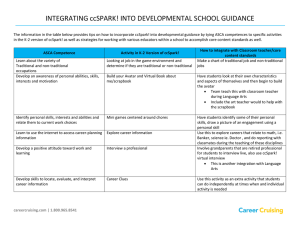

advertisement