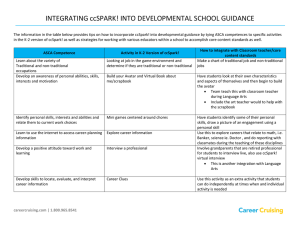

: n o ti

advertisement