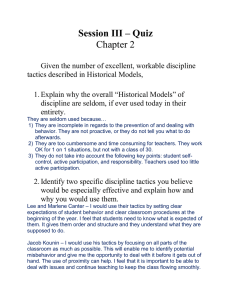

TACTICS Policy and strategic impacts, implications and recommendations

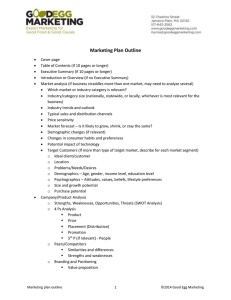

advertisement