MINUTES ACADEMIC STANDARDS COMMITTEE April 20, 2007 Present:

advertisement

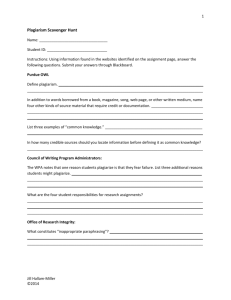

MINUTES ACADEMIC STANDARDS COMMITTEE April 20, 2007 Present: Gary McCall, Mike Spivey, Mark Martin, Debbie Chee, Bill Kupinse, John Finney, Chris Kline, Brad Tomhave, Wade Hands, Greta Austin, Ken Clark, Seth Weinberger, Kevin David, Melissa Bass, Alison Tracy Hale, Jack Roundy 1. Minutes: The April 6 minutes were approved as submitted. 2. Announcements: Kline thanked the committee for its service and especially lauded John Finney for years of meritorious contributions on the occasion of his final ASC committee meeting. 3. Petitions Committee (PC) Actions: Tomhave provided the following report of PC actions since our last meeting. Date 4/11/07 4/18/07 Year-to-date Approved 3 (2 PPT + 1 R) 6 (1 PPT + 1 R) 169 (48 PPT + 38 R) Denied 1 0 41 No Action 0 0 1 Total 4 6 211 Tomhave also announced that he would be soliciting summer PC members in the coming weeks. Finally, he also noted that Clevenger is expected to nominate her student member replacement for next year, and said he would contact her about this. 4. Hearing Board Update: Finney reported that an unexpected academic dishonesty charge has recently arisen. On April 30 the board will meet to consider the case. 5. Academic Honesty: Weinberger and Austin brought revised language for the Logger (attached), inviting committee input on its disposition. Martin reported that Spivey has also supplied some proposed language. Spivey was ambivalent about whether his proposed computer science and mathematics language should be spliced into the text or given a separate section. Weinberger thought that we might not want all of the subcommittee’s proposed language in the policy statement—illustrative and support materials could be linked online, while the policy text could remain more concise. Kupinse and Chee liked the link idea. Weinberger said he thought the only downside to relegating some of our material to links would be the possibility that students might not follow the links. Chee thought if we were clever about making the links userfriendly, students would follow them. Weinberger said he thought our next decision was to determine what are the “bare bones” of the policy, and therefore essential to include in the Logger, and what elements could be linked. Tracy Hale wondered whether any links we include would not also therefore be part of the policy. Finney said he thought we would continue to have a hard copy of the Logger, and that it should include the same text that we offer online. Our new material ought to be in it, he thought. So in that sense, the new materials should be thought of as part of the policy, even if illustrative. He argued that we ought first to think of arranging things in the hard copy Logger, then adapt the web accordingly. Kupinse wondered if it would it be helpful to use web links to other sources (like Princeton’s material) without including them in our policy. Weinberger and Kupinse agreed that the problems with linking to off-campus sites were 1) that we have no control over linked sources (as they change and/or disappear), and 2) that those sources may not be entirely consistent with our policy. Finney argued that what is most important is the policy itself. In the 80’s, we began to include examples to explicate that policy. In our current digital environment, academic honesty issues have become more complicated, and accordingly we are adding more illustrative material, though we are not making substantive changes to the policy. He argued that we need to keep the policy front and center, then indicate what is illustrative. Tracy Hale argued that we should be careful our posted policy does not stand in for or contradict specific guidelines within disciplines. But she thought we could safely promulgate a general policy with various examples. Chee thought we could field test a web presentation with a subset of our student body to see how students use it and whether they find it helpful. Weinberger interjected that he didn’t want us to lose the idea that we can use the plagiarism test as a teaching tool. Kline suggested that since we are so near to the end of term, we might all take the subcommittee materials away from this meeting, read them carefully over the summer, then decide what we would like to test out with our students in the coming fall. Roundy suggested that we ask Barb Weist, Puget Sound web manager, to create a test site which could be accessed by committee members and any students we wish to involve in our try-out, without full deployment to the full community until we feel confident in our changes. Kline concurred, suggesting that committee members try it out with their students in the fall. Chee and Kline offered to work on a test site in the summer. Martin wondered if we could get students to try out the plagiarism test before next fall. Chee doubted that this could be done before then, given how close we are to the end of this academic year. Weinberger argued that if we are to adopt the plagiarism test, it must be adapted to online use. Once this is done, McCall argued (much to Tomhave’s dismay), we should make students take the test before they are allowed to register for classes. Kline wondered if we could require entering students to take the test before they come to campus in the fall. Chee didn’t think that was practical. Kline said on second thought that we should be teaching students about academic honesty as we are bringing them into our community, not before. Austin said she intended to use the plagiarism test in Prelude, and her commitment was quickly followed by those of Weinberger, Bass, Tracy, Martin, McCall (and Taylor, in absentia, as a team-teacher). As the meeting was winding down, Kline said she had delivered the ASC final report to the Faculty Senate on April 16. She noted that she promised the ASC would continue to review our new withdrawal policy in the coming academic year, and she reported on a brief discussion of the registrar’s proposed mode of reflecting study abroad credit on the transcript. We adjourned at 8:52, and as this was the final ASC meeting of the year, a valedictory photo was taken in honor of John Finney. Respectfully submitted by the ASC amanuensis, Jack Roundy ACADEMIC HONESTY The University as an Intellectual Community The University of Puget Sound is, first and foremost, an intellectual community. Every college or university is an environment rich in intellectual, technological, and information resources where students and faculty members come together to pursue their academic interests. All of us are here to learn from each other and to teach each other, both in our individual quests to mature as thinkers, scholars, and researchers, and in our collective effort to advance and refine the body of human knowledge. All of us benefit from the free exchange of ideas, theories, solutions, and interpretations. We test our own thoughts informally among friends or in class, or more formally in papers and exams; we profit by analyzing and evaluating the ideas of our classmates, friends, advisers, and teachers. Trust is the central ethic of such an intellectual community, in several respects. Trust that your ideas, no matter how new or unusual, will be respected and not ridiculed. Trust that your ideas will be seriously considered and evaluated. Trust that you can express your own ideas without fear that someone else will take credit for them. And, others need to be able to trust that your words, data, and ideas are your own. The right to intellectual ownership of original academic work is as important to the life of the university as the right to own personal possessions. However, our intellectual community is much greater than the current population of UPS students, faculty, and staff. Such an intellectual community transcends both time and space to embrace all of the contributors to human knowledge. We may find their theories in textbooks, or their words in books of poetry, or their thoughts in library volumes or journals, or their data on the World Wide Web. Through the work they have produced in times past or are producing now across the globe, they share with us their intellectual efforts, trusting that we will respect their rights of intellectual ownership. As we at the University strive to build on their work, all of us -- from freshman to full professor -- are obligated by the ethic of intellectual honesty to credit that work to its originator. [Taken from Princeton’s Academic Integrity statement; language should be changed] Honesty is an appropriate consideration in other ways as well, including but not limited to the responsible, respectful use of library books; responsible conduct in examinations; responsibility in meeting course assignments; the securing of legitimate signatures as needed; the respectful use of computer accounts; the responsible use of the internet and the world wide web, and behavior on study abroad programs which respects the rights and safety of others. The suspicion of dishonesty in the academic community is a serious matter because it threatens the atmosphere of respect essential to learning. Academic dishonesty can take many forms, including but not limited to the following: plagiarism, which is the misrepresentation of someone else’s words, ideas, research, images, video clips, or computer programs (including stacks, spreadsheet macros, command files, etc.) as one’s own; submitting the same paper or computer program or portion thereof for credit in Deleted: The University is a community of faculty, students, and staff engaged in the exchange of ideas contributing to individual growth and development. Essential to the successful functioning of the academic community is a shared sense of enthusiasm for learning and respect for other persons. The successful functioning of the academic community also demands honesty, which is the basis of respect for both ideas and persons. In the academic community there is an ongoing assumption of honesty at all levels. In particular, there is the expectation that work will be independently thoughtful and responsible as to its sources of information and inspiration. more than one course without prior permission; collaborating with other students on papers or computer programming assignments and submitting them without instructor permission; cheating on examinations; mistreatment of library materials; violation of copyright laws (see the Copy Center’s handbook for a summary of copyright guidelines); forgery; and misuse of academic computing facilities. In situations involving suspicion of dishonesty, procedures and sanctions established for the Hearing Board (see below) shall be followed. Plagiarism A faculty member or the Hearing Board may make a judgment that plagiarism has occurred on grounds other than a comparison of the student’s work with the original material. Internal stylistic evidence, comparison of the work that is suspect with other written work by the same student, the student’s inability to answer questions on what he or she has written, may all support a judgment of plagiarism. The following discussion of plagiarism, designed to diminish misunderstanding of this serious breach of academic honesty, is adapted (with permission) from Sydney and Elizabeth Cowen, Writing, New York, John Wiley and sons, 1980, pp. 470-472. To plagiarize means to take someone else’s words and/or ideas and put them into writing as though they were yours. Some people deliberately steal other writers’ works, but much plagiarism in students’ research papers occurs through carelessness, uncertainty, or ignorance. When to Cite Sources You will discover that different academic disciplines have different rules and protocols concerning citation -- when and how to cite sources. For example, some disciplines use more traditional footnote form and others use numerical markers in the text; some require complete bibliographic information on all works consulted and others append only a "List of Works Cited." As you decide on a concentration and begin advanced work in your department, you will need to learn the particular protocols for your discipline. At the end of this booklet, you will find a brief sampling of more commonly used bibliographic formats. The five basic rules described below apply to all disciplines and should guide your own citation practice. Even more fundamental, however, is this general rule: when in doubt whether or not to cite a source, do it. You will certainly never find yourself in trouble if you acknowledge a source when it is not absolutely necessary; it is always preferable to err on the side of caution and completeness. Better still, if you are unsure about whether or not to cite a source, ask your professor or preceptor for guidance before submitting the paper. 1. Direct Quotation. Any verbatim use of the text of a source, no matter how large or small the quotation, must be clearly acknowledged. Direct quotations must be placed in quotation marks or, if longer than three lines, clearly indented beyond the regular margin. The quotation must be accompanied, either within the text or in a footnote, by a precise indication of the source, identifying the author, title, and page numbers. Even if you use Deleted: Formatted: Indent: Left: 0 pt, First line: 0 pt only a short phrase, or even one key word, you must use quotation marks in order to set off the borrowed language from your own, and cite the source. 2. Paraphrase. If you restate another person’s thoughts or ideas in your own words, you are paraphrasing. Paraphrasing does not relieve you of the responsibility to cite your source. You should never paraphrase in the effort to disguise someone else’s ideas as your own. If another author’s idea is particularly well put, quote it verbatim and use quotation marks to distinguish his or her words from your own. Paraphrase your source if you can restate the idea more clearly or simply, or if you want to place the idea in the flow of your own thoughts. If you paraphrase your source, you do not need to use quotation marks. However, you still do need to cite the source, either in your text or a footnote. You may even want to acknowledge your source in your own text ("Albert Einstein believed that…"). In such cases, you still need a footnote. 3. Summary. Summarizing is a looser form of paraphrasing. Typically, you may not follow your source as closely, rephrasing the actual sentences, but instead you may condense and rearrange the ideas in your source. Summarizing the ideas, arguments, or conclusions you find in your sources is perfectly acceptable; in fact, summary is an important tool of the scholar. Once again, however, it is vital to acknowledge your source -- perhaps with a footnote at the end of your paragraph. Taking good notes while doing your research will help you keep straight which ideas belong to which author, which is especially important if you are reviewing a series of interpretations or ideas on your subject. 4. Facts, Information, and Data. Often you will want to use facts or information you have found in your sources to support your own argument. Certainly, if the information can be found exclusively in the source you use, you must clearly acknowledge that source. For example, if you use data from a particular scientific experiment conducted and reported by a researcher, you must cite your source, probably a scientific journal or a Web site. Or if you use a piece of information discovered by another scholar in the course of his or her own research, you must acknowledge your source. Or perhaps you may find two conflicting pieces of information in your reading -- for example, two different estimates of the casualties in a natural catastrophe. Again, in such cases, be sure to cite your sources. Information, however, is different from an idea. Whereas you must always acknowledge use of other people’s ideas (their conclusions or interpretations based on available information), you may not always have to acknowledge the source of information itself. You do not have to cite a source for a fact or a piece of information that is generally known and accepted -- for example, that Woodrow Wilson served as president of both Princeton University and the United States, or that Avogadro’s number is 6.02 x 1023. Often, however, deciding which information requires citation and which does not is not so straightforward. The concept of "common knowledge" can never be an objective criterion for the obvious reason that what is commonly known will vary radically in different places and times. Human understanding is constantly changing, as the tools by which we can observe and comprehend the universe develop and as the beliefs that may shape that understanding evolve. In medieval times, for example, it was an incontrovertible fact that the Earth was at the center of the universe. What a Chinese acupuncturist knows about human anatomy and health is remarkably different from what an American-trained surgeon knows. And what Princeton concentrators in molecular biology know today about the human genome would bewilder and astound Princeton biology students of only two generations ago. Although it is not worth belaboring this point further, it is definitely worth considering some of the implications for properly acknowledging the sources of the information you use in your own academic work. What is considered "knowledge" or "fact" for one group may be only theory or opinion for another, as the recent controversy about teaching evolution and creationism in the public schools reminds us. To complicate matters, each discipline has its own evolving definitions, and its own tests, for what constitutes a "fact." And to make matters worse, even within a discipline, experts often disagree. The main point is that you may be unable to make informed decisions concerning what is and what is not “common knowledge.” That will be less true as you get to know a topic in depth, as you will for your senior thesis. But, especially in fields with which you are less familiar, you must exercise caution. The belief that an idea or fact may be “common knowledge” is no reason not to cite your source. It is certainly not a defense against the charge of plagiarism, although many students offer that excuse during the disciplinary process. Keeping in mind that your professor is the primary audience for your work, you should ask your professor for guidance if you are uncertain. If you don’t have that opportunity, fall back on the fundamental rule: when in doubt, cite. It is too risky to make assumptions about what is expected or permissible. 5. Supplementary Information. Occasionally, especially in a longer research paper, you may not be able to include all of the information or ideas from your research in the body of your own paper. In such cases, you may want to insert a note offering supplementary information rather than simply providing basic bibliographic information (author, title, date and place of publication, and page numbers). In such footnotes or endnotes, you might provide additional data to bolster your argument, or briefly present a alternative idea that you found in one of your sources, or even list two of three additional articles on some topic that your reader might find of interest. Such notes demonstrate the breadth and depth of your research, and permit you to include germane, but not essential, information or concepts without interrupting the flow of your own paper. In all of these cases, proper citation requires that you indicate the source of any material immediately after its use in your paper. For direct quotations, the footnote (which may be a traditional footnote or the author’s name and page number in parenthesis) immediately follows the closing quotation marks; for a specific piece of information, the footnote should be placed as close as possible; for a paraphrase or a summary, the footnote may come at the end of the sentence or paragraph. Simply listing a source in your bibliography is not adequate acknowledgment for specific use of that source in your paper. This point is extremely important and too often misunderstood by students. If you list a source in your bibliography, but do not properly place citations in the text of your paper, you can be charged with plagiarism. In Committee on Discipline hearings, students who did not set off verbatim quotations with quotation marks and footnotes, or who used ideas or information from a source without proper citation in the paper itself, sometimes argue their innocence because the source is listed in their bibliography. That puts the Committee in the difficult position of determining whether the error was a mistake based on misunderstanding the rules of citation or whether it was an intentional effort to deceive the reader. Either way, the student will be found responsible for the act of plagiarism. [Taken from Princeton’s Academic Integrity statement; language should be changed] Some students may be reluctant to include many footnotes or citations. They may think that including many citations makes their work look unoriginal. This is not true. First, footnotes or references allow others to see what material you have used in order to arrive at your conclusions. Second, citing recognizes your intellectual debts to those who have worked on the same topic before you. Third, providing references enables other readers to check your statements and to find more information on their own. When in doubt, you should cite more rather than less. Some authors have suggested helpful ways to avoid plagiarism: “Be conscious of where your eyes are as you put words on paper or on a screen. If your eyes are on your source at the same moment your fingers are flying across the keyboard, you risk doing something that weeks, months, even years later could result in your public humiliation. Whenever you use a source extensively, compare your page with the original. If you think that someone could run her finger along your sentences and find synonyms or synonymous phrases for words in the original in roughly the same order try again. You are least likely to plagiarize inadvertently if, as you write, you keep your eyes not on your source but on the screen or on your own page, and you report what your source has to say after those words have filtered through your own understanding of them.” 1 Deleted: Some simple rules will help each student know how to avoid plagiarism:¶ ¶ 1. Always put quotation marks around any direct statement from someone else’s work (or indent and single-space extended quotations). Always give a footnote, endnote, or other form of citation for this quotation.¶ 2. Cite any paraphrase of another writer’s ideas or statements.¶ 3. Cite any thoughts you got from a specific source in your reading.¶ 4. Cite any material, ideas, thoughts, etc., you got from your reading that can’t be described as general knowledge.¶ 5. Cite any summary (even if in your own words) of a discussion from one of your sources.¶ 6. Cite any charts, graphs, tables, etc., made by others or any you make with others’ information.¶ 7. Cite any computer algorithm you incorporate into a computer program if you did not write or create the algorithm yourself. Formatted: Indent: Left: 0 pt, First line: 0 pt Formatted: Font: 12 pt Examples of Plagiarism Example 1: Original Version, Quoted Directly from Source: Two plausible explanations exist for the Anasazi departure from a homeland where life was full and complete: either life had ceased to be good and they were starved out, or they were driven out by someone else. There are strong indications that a severe drought extended over the plateau from 1276 to 1299, and quite possibly the Anasazi found agriculture as they had come to depend on it impossible. There are subtle inconsistencies 1 Wayne Booth, Gregory Colomb and Joseph Williams, The Craft of Research (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 170. Formatted: Font: 12 pt Formatted: Font: Bold to the theory, however, that tend to impeach its universality, giving rise to the second possibility. Wandering Shoshonean hunters—raiders by nature—had begun to roam the plateau somewhat earlier, and given the fortresslike quality of most Anasazi pueblos and cliff dwellings, it seems possible that these raiders had begun to make part, or most, of their living by preying on the vulnerable fields of the agriculturists. If this was the case, the Anasazi would in time be forced out. Whatever the answer, and it may be a combination of both, the Anasazi departed to other regions. -Donald C. Pike Student Version 1: Nobody really knows why the Anasazi, the cliff dwellers, left their homes, but two possible reasons are given. The drought of 1276-1299 may have destroyed agriculture as the Anasazi had come to depend upon it. The Shoshonean hunters, raiders by nature, may have also begun preying on the vulnerable fields and crops of the Indians. No one knows for sure, but these two explanations, perhaps even in combination, may explain the abandoned cliff dwellings. Remarks: The writer has clearly plagiarized. Here are the reasons this is true. 1. The writer uses information that is not common knowledge, information received from reading the original paragraph, and yet not footnoted. 2. The writer uses many of the author’s exact words and phrases—steals them, in fact—and does not mention that the words and phrases are not original. Even though some of the words are the writer’s, credit is not given for the knowledge in the paragraph itself nor for the author’s direct words. Student Version 2: Authorities often give two explanations for the departure of the Anasazi from their homeland. Either they were starved out, or they were driven out. There was a drought from 1276 to 1299, and it is possible that this drought affected the farming drastically.1 Also, there was a roaming band of raiders, the Shoshonean, who may have attacked the Anasazi.2 Whatever the answer, and maybe it was a combination of both the drought and the invaders, the Anasazi departed to other places. Remarks: The student is still plagiarizing. Even though the two facts have been footnoted, the writer is still passing off many of the author’s words as though they were the writer’s own. Just footnoting the two facts does not give the student the license to use the author’s phrases and words without giving credit. Student Version 3: Anybody who has ever seen or read about the Indian cliff dwellings is perplexed by the question, why did the Anasazi leave? Their homes were very advanced in structure and design. They had good farms. There are two explanations generally given. The Indians may have left because of a severe drought that occurred in 1276-1299.1 They may also have been forced out by the Shoshonean, a tribe of raiders.2 Nobody really knows for sure. Whatever the reason—whether it was a drought, the invaders or a combination of both—the Anasazi left their homes, and all that remains there now are the magnificent cliff dwellings that fascinate and intrigue everybody who sees them.3 Remarks: Finally, the student has stopped plagiarizing. The first two sentences could be considered general knowledge or conclusions the writer came to after a preliminary general reading, therefore not attributable to any particular source. The two reasons given by Donald Pike in the original paragraph have been clearly footnoted. Even the last sentence has been footnoted because the writer had used Pike’s idea that the reason might be a combination of both. Even though the writer’s original words were used in the last paragraph, credit has been given to the author’s idea because the information was not known until read. Example Two: Use of Internet Websites I: Example where website is used verbatim: a) Original website: (http://www.cfr.org/publication/12717/alqaeda_in_the_islamic_maghreb_aka_salafist_group_for_pre aching_and_combat.html?breadcrumb=%2Fpublication%2Fpublication_list%3Ftype%3Dbackgrou nder) Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (aka Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat) Author: Andrew Hansen Introduction Reports from North Africa point to a recent resurgence in terrorist activity by several local Islamist movements, the most prominent of which is the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC). An Algeria-based Sunni group that recently renamed itself al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, the organization has taken responsibility for a number of terrorist attacks in the region, declared its intention to attack Western targets, and sent a squad of jihadis to Iraq. Experts believe these actions suggest widening ambitions within the group’s leadership, now pursuing a more global, sophisticated and better-financed direction. Long categorized as part of a strictly domestic insurgency against Algeria’s military government, GSPC claims to be the local franchise operation for al-Qaeda, a worrying development for a region which has been relatively peaceful since the bloody Algerian civil war of the 1990s drew to a close. What is al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb? The group originated as an armed Islamist resistance movement to the secular Algerian government. Its insurrection began after Algeria’s military regime canceled the second round of parliamentary elections in 1992 after it became clear the Islamic Salvation Front, a coalition of Islamist militants and moderates, might win and take power. The GSPC declared its independence from another insurgent group, the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) in 1998, believing the GIA’s brutal tactics were hurting the Islamist cause. The GSPC gained support from the Algerian population by vowing to continue fighting while avoiding the indiscriminate killing of civilians. The group has since surpassed the GIA in influence and numbers to become the primary force for Islamism in Algeria, with the majority of its members refusing government offers of amnesty after Algeria’s civil war of the mid-1990s. According to a 2005 U.S. State Department report on terrorism, its ranks have dwindled to only a few hundred from nearly 28,000 at the height of its power. b) Plagiarized Text: Reports from North Africa point to a recent resurgence in terrorist activity by several local Islamist movements, the most prominent of which is the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC). An Algeria-based Sunni group that recently renamed itself al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, the organization has taken responsibility for a number of terrorist attacks in the region, declared its intention to attack Western targets, and sent a squad of jihadis to Iraq. Experts believe these actions suggest widening ambitions within the group’s leadership, now pursuing a more global, sophisticated and better-financed direction. Long categorized as part of a strictly domestic insurgency against Algeria’s military government, GSPC claims to be the local franchise operation for al-Qaeda, a worrying development for a region which has been relatively peaceful since the bloody Algerian civil war of the 1990s drew to a close. The group originated as an armed Islamist resistance movement to the secular Algerian government. Its insurrection began after Algeria’s military regime canceled the second round of parliamentary elections in 1992 after it became clear the Islamic Salvation Front, a coalition of Islamist militants and moderates, might win and take power. The GSPC declared its independence from another insurgent group, the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) in 1998, believing the GIA’s brutal tactics were hurting the Islamist cause. The GSPC gained support from the Algerian population by vowing to continue fighting while avoiding the indiscriminate killing of civilians. The group has since surpassed the GIA in influence and numbers to become the primary force for Islamism in Algeria, with the majority of its members refusing government offers of amnesty after Algeria’s civil war of the mid-1990s. According to a 2005 U.S. State Department report on terrorism, its ranks have dwindled to only a few hundred from nearly 28,000 at the height of its power. Works Cited: Hansen, Andrew, “Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb,” Council on Foreign Relations Backgrounder, Feb. 26, 2007 (available at http://www.cfr.org/publication/12717/alqaeda_in_the_islamic_maghreb_aka_salafist_group_for_preaching _and_combat.html?breadcrumb=%2Fpublication%2Fpublication_list%3Ftype%3Dbackgrounder). Explanation: Even though the source website is listed in the “Works Cited” page, the text has been lifted word-for-word, and represents no original contribution. Furthermore, since the text is identical to the source, the entire quote should be in block quote form to indicate that the wording is taken from another source. II: Example in which language of website has been paraphrased: a) ORIGINAL: Literally, the word hijab means "curtain". In the Qur’an the term hijab is not used as a reference to women’s clothing; rather, it was the screen behind which the Muslims were told to address the Prophet’s wives. (The term is also used to describe the "screen" separating God from Moses, as he received divine revelation.) When the Prophet’s wives went out, the screen consisted of a veil over their face. It does not appear that covering the face was adopted by the other Muslim women at the time since it was a special injunction for the Prophet’s wives as is clear in the verses below: And (as for the Prophet’s wives) when you ask for anything you want (or need), ask them from behind a hijab (screen), that makes for greater purity of your hearts. (33:53) O wives of the Prophet! You are not like any of the (other) women: If you do fear (God) be not too complaisant of speech, lest one in whose heart is a disease should be moved with desire: but speak with a speech (that is) just. (33:32) http://www.mwlusa.org/publications/positionpapers/hijab.html b) PLAGIARIZED The literal meaning of the word hijab is “curtain”; the Qur’an also describes the partition or veil between God and Moses as a hijab. The Qur’an uses the term hijab to describe not women’s clothing, but instead the screen or partition from behind which Muslims must speak to the wives of the Prophets. (The Prophet’s wives used a veil to cover their faces when they went outside in public. This requirement was apparently limited only to the Prophet’s wives and did not apply to women in Medina in general (see, e.g., Q 33:32 and 33:53). Explanation: Although not every single sentence follows in the same order, the ideas are all the same. The sentences have been carefully reworded and rephrased, but they clearly are based on the Muslim Women’s League website. Honest Use of the Internet and the World Wide Web While the Internet has made research much easier, it has also made plagiarism – both intentional and accidental – easier as well. Even though a website may lack an identifiable author and is widely and publicly available, that does not mean that the information contained on that site is in the public domain. If others have made the effort to develop a website and disseminate information, their work must be recognized when you use that information for your own purposes. Contrary to a common misperception, the vast majority of material on the internet is not in the public domain. Materials acquired from the internet must be properly cited. The following URL on the University of Puget Sound library web site contains examples of proper methods of citing web pages, electronic journals, newspaper articles, reference works, electronic texts, listserv messages, and email messages: http://library.ups.edu/research/guides/citeurls.htm. In addition, whenever one uses the ideas, graphic images, pictures, video clips, or any other material from the internet, that material must be properly cited. To fail to do so is to commit plagiarism. Faculty are aware of the term paper sites on the web that tempt students with the promise of readymade papers, and documents obtained in this manner are surprisingly easy to trace. Honesty in Computer Programming Honesty is expected in completion of computer programming assignments, as in completion of all other assignments. Nothing in this document is intended to discourage Formatted: Font: 12 pt students from working with colleagues or from consulting the computer science literature in order to gain a deeper understanding of computer programming. Discussion of a programming assignment, helping each other to understand the purpose and requirements of the assignment, discussions on general design ideas, and mutual help on problems of syntax, are all encouraged. But team efforts on detailed design, implementation, and testing are permitted only when this team effort is a clearly stated part of the assignment. If your instructor permits the use of algorithms found in the literature, those algorithms should be cited in the same manner you would cite published material in a term paper. Here are three activities which are violations of honesty standards in the completion of computer programming assignments: 1. Team Efforts: Unless the instructor states otherwise, computer programming assignments must be completed individually. Permitting work done by a group is unfair to students who make individual efforts to complete the programming assignment. Beyond consultation about the general design of a program and discussions about syntax errors, consulting with your colleagues on a program assignment is not permitted. In particular, team work on detailed design, implementation, or testing is not permitted. Work is a team effort whenever persons work individually to construct parts of a programming assignment, fitting them together into one program, or whenever persons work together to write the programming assignment as a group. 2. Copying a computer program is plagiarism and will be dealt with like all other instances of plagiarism. Copying occurs whenever: a. A copy of a program not your own which can be used to meet the requirements of a programming assignment is found in your account. Computer accounts are not private property. Computer accounts may be reviewed by faculty or by the coordinator of Academic Computing. b. An algorithm in a program submitted for a grade is copied without citation from the literature. Unless otherwise specified by the instructor, such algorithms should not be a part of your program. c. Your program is a transformation of a program written by another person, created, for example, from that program by changing variable names or interchanging blocks of code. 3. Writing all or part of a program for another student, or submitting all or part of a program for a grade written by another person, is not permitted. The Spectrum of Plagiarism While everyone would agree that copying another student’s term paper is plagiarism, and that looking at another student’s exam is cheating, there are some more nuanced instances where students might not be clear whether an act would be viewed as plagiarism. The weight of the assignment does not determine whether it can be copied; rather it is whether the work represent your own original effort. For example, replicating a pre-lab assignment is plagiarism. On the other hand, working together on difficult problems can yield similar results which would not be considered plagiarism. Students sometimes offer other forms of mutual help to one another. Most fall into a “gray area” that requires Formatted: Font: 12 pt using your own good judgment. As always, it is better to be cautious. Discussing ideas for paper topics with a classmate you know and trust is fine, and the exchange of ideas will probably stimulate and benefit both of you. Proofreading a friend’s paper for typographical and grammatical errors is also acceptable, even advisable (so long as the professor permits it). Making a small suggestion if a point is not as clear as it could be is also fine. Rewriting parts of the paper is not. Ask your instructor before comparing and analyzing your laboratory data with your classmates. Avoid temptation by solving your problem sets privately. When in doubt, ask. Each professor has his or her own expectations and requirements. Be sure you know what these are. Ultimately, the decision whether plagiarism has occurred rests with each individual professor. Response to Instances of Plagiarism and Other Acts of Academic Dishonesty Introduction. Faculty are urged to review the definition of plagiarism with their classes, noting the specific steps that will be taken by the faculty member if an instance of plagiarism or other act of academic dishonesty is observed. (Throughout the remainder of this section the term “academic dishonesty” is used to include plagiarism and other acts of academic dishonesty). 1. If a faculty member has reason to suspect academic dishonesty, the following actions are taken: a. The faculty member may consult with the department chair, program director, or the registrar regarding his/her suspicion of academic dishonesty. b. The faculty member notifies the student that she or he suspects an instance of academic dishonesty and that an appropriate response will be made. c. The faculty member meets with the student as a part of the process of determining if an instance of academic dishonesty has occurred. This meeting may at the faculty member’s discretion include the department chair or program director. If the student is not available on campus because the semester has ended or for other reasons, the meeting can happen by phone, by mail, or by email. If the student is unreachable, then the faculty member determines responsibility based on the available evidence. d. If the faculty member determines that an instance of academic dishonesty has occurred, he or she submits to the Registrar an Academic Dishonesty Incident Report (available from the Office of the Registrar), including reasonable documentation and the recommended penalties to be imposed. The faculty member must provide a copy of the form to the student. The Registrar informs the faculty member if this is the student’s first offense or not. e. If there has been no prior reported instance of academic dishonesty, the penalties imposed by the faculty member conclude the case unless either the student or the faculty member asks for a Hearing Board. If either asks for a Hearing Board, the dean will meet with both parties to seek an appropriate resolution. The dean may Formatted: Font: 12 pt Formatted: Font: Not Bold also consult with the chair or director of the department or school involved. If no resolution is possible, a Hearing Board will be convened. 2. When step 1d is reached and if a previous act of academic dishonesty has been reported to the Office of the Registrar, the following actions are taken: a. The Registrar notifies the faculty member that at least one previous case has been reported. b. The Registrar asks that a Hearing Board be convened to consider the case and to apply appropriate sanctions (see the next section). The faculty member’s proposed sanctions are forwarded to the board; however, depending on the gravity of the offense, the board may impose any of the sanctions described in Step 4 of the Hearing Board procedures listed below. 3. Academic Dishonesty Incident Report forms are retained in a confidential file maintained by the Registrar to provide a record of academic dishonesty for a Hearing Board should a student be the subject of more than one report. Academic Dishonesty Incident Reports are disposed of following a student’s graduation or four years following a student’s last enrollment, provided a Hearing Board does not direct otherwise. Contents of the Academic Dishonesty Report Forms and subsequent Hearing Board actions are revealed only with the written consent of the student, unless otherwise permitted or required by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act. No entry is made on the student’s permanent academic record of an instance of academic dishonesty, unless so directed by a Hearing Board. Hearing Board Procedures in Matters of Plagiarism and other Acts of Academic Dishonesty The Hearing Board functions as a fact-finding group so that it may determine an appropriate resolution to the charge of academic dishonesty. Its hearings are informal, and the parties directly involved are expected to participate. To make knowingly false statements or to otherwise act with malicious intent within the provisions of Hearing Board procedures shall constitute grounds for further charges of academic dishonesty. 1. If an academic dishonesty complaint has been referred to the Hearing Board, a Hearing Board is convened to review the case. 2. The Hearing Board consists of: the academic dean (chair) and the dean of students, or their designees; two faculty members selected by the chair of the Academic Standards Committee; and two students selected by the chair of the Academic Standards Committee in consultation with the president of the Associated Students. The parties directly involved may have one other person present who is not an attorney. The chair designates a secretary, responsible for recording the salient issues before the board and the actions of the board. 3. The parties involved are asked to submit written statements and any written statements submitted are circulated by the chair to the members of the Hearing Board. All parties have the right to appear before the board, and may be asked to appear before the board, but the hearing may proceed regardless of appearance or failure to appear. The board reviews written statements submitted by the parties and any such other relevant material which the chair of the board deems necessary. When all presentations are complete, the board, in executive session, reaches its resolution of the problem. 4. The Hearing Board may find the allegations not to be factual, or the Hearing Board may impose sanctions. Sanctions include, but are not limited to, warning, reprimand, grade penalty, removal from the course or major, probation, dismissal, suspension, and/or expulsion. The conclusion is presented in writing to the parties directly involved and to such other persons as need to know the results of the hearing. If some action is to be taken, the chair of the board is responsible for requesting that the action be performed and in ensuring that such action is taken. Upon completion of the hearing, the chair maintains a file of relevant material for a period of at least two years. 5. The decision of the Hearing Board is final.