A F T

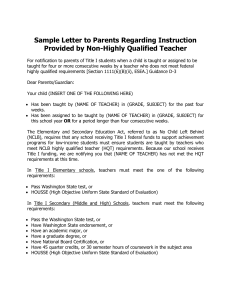

advertisement