CEPA Working Paper No. 15-07

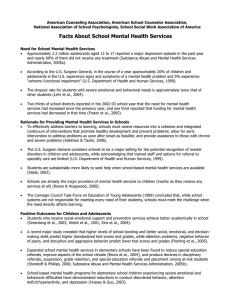

advertisement