Bulletin Striking a path Defining the responsible university Supporting early career academics

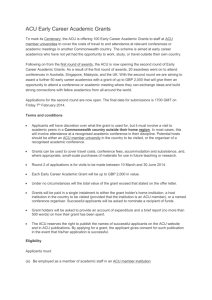

advertisement