Document 12281747

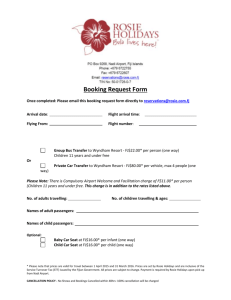

advertisement