26 O

advertisement

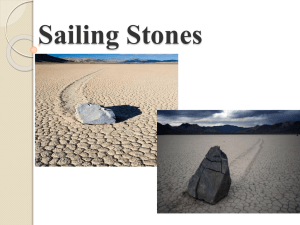

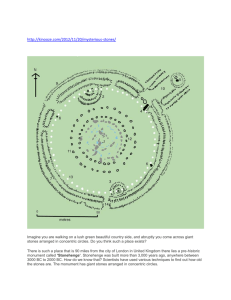

26 EDUCATION OMAN DAILY Observer TUESDAY, DECEMBER 15, 2009 Discovery indicates that such stones can also be climatic indicators Discovery of hunting stones in Al Mudhaibi dated to the Seventh Millennium BC S aid bin Salem Said al Jahafi, a student in the College of Engineering at SQU was not aware that his decision to take an elective from the College of Arts would lead him to contribute to an important archaeological discovery in the Al Mudhaibi district. In one of the most recent archaeological studies executed by SQU, an archaeological team headed by Professor Ali Altijani al Mahi, Head of the Department of Archeology conducted an archaeological survey of the Al Mudhaibi area after Al Jahafi found by sheer accident kinds of stones that was used in hunting animals called Tethering Stones. Such stones were first discovered in North Africa in Algiers, Tunis, Chad and Northern Sudan. The archaeological survey conducted by the SQU team revealed the existence of a number of these stones scattered over a large area in Al Mudhaibi. Professor Altijani says that SQU has graciously accepted to finance this important study by providing the needed means and facilities to conduct the field work. He goes on to say that tethering stones can be viewed as an advanced hunting device since they represent an amalgamation of inventiveness, knowledge and experience arrived at through experiment. Indeed they are the work of the hunter's imagination. The study explores a new aspect of human lifestyle at that time as well as the nature and climate of that area. The archaeological survey conducted by the SQU team proved that the Al Mudhaibi stones belong to the seventh millennium BC; this discovery was arrived at through the analysis of the soil in which these stones were found. The seventh millennium BC is known as a wet phase, which suggests that the coastal area of Al Mudhaibi had a dense vegetation cover, and thus was inhabited by different kinds of animals hunted for food. D r Ihsan al Lawati opens a window onto modern Persian short story. His book is considered the first Omani attempt to translate narrative Persian texts into Arabic. A Window on the Modern Persian Short Story is hailed as one of the few pioneering studies which survey various patterns of modern Persian short story translated into Arabic by Dr Ihsan al Lawati of SQU’s Department of Arabic. The book consists of nine short stories written by most prominent Iranian writers of this form covering several generations. Reading this volume is a unique experience especially for those who are fond of world literature, as they will discover that there are many worlds that they have not yet fathomed. Persian literature appears in its full glory in the wonderful texts carefully chosen by Dr Al Lawati to give the reader a panoramic view of Iranian daily life concerns. He does this in a charming language which combines simplicity with richness, a phenomenon found in nineteenth and twentieth century Russian writers like Turgenev, Dostoyevesky, Tolstoy, Chekov, Gogol, and indeed in other great writers whose masterpieces have enriched world literature. Not only narratives' emphasis on details raises the readers' wonder, it also makes them change their time and place and takes them to join another world, and become part of its events. This is what real literature does when it is absorbed by the reader, and it is certainly the case when reading Dr Al Lawati's book. Dr Ihsan al Lawati says that his text is a window through which Arab readers can view the modern Persian language innovations within the realm of the short story. This concern is important for Arab short story readers, especially authors or critics among them, because of the strong historical associations which exist between Persian and Arabic. Dr Al Lawati has chosen to translate from Africa which were used for hunting. The elongated rocks are grooved in the middle, and a rope was fastened around the grooves. The other end of the rope was tied to a noose which formed a loop by means of a slipknot. The loop could instantly tighten if the rope was pulled. Thus the movement of the trapped animal would be slowed down making it easier to hunt. The length of the rope depended upon the weight of the stone: the heavier the stone was, the shorter the rope. The study located about twenty specimens of tethering stones of different sizes and weights. The geological analysis of the soil in which they were found indicated that they belong to a wet phase of the Holocene. After the hunting traps were reconstructed, the stones, their geographical locations, and their weights were examined. These investigations indicated that these stones were taken away from their natural location, placed elsewhere and grooved in the middle in order to be used for hunting. Dean Thuwayba al Barwani discusses research in the College of Education O Big game As to whether big game like giraffe, elephant and rhinoceros existed in the Al Mudhaibi area, where the tethering stones were found, Professor Altijani explains that the variation in weight and size of the stones (the smallest weighed 4 kilograms and the heaviest weighed 55) theoretically indicates the presence of such huge animals. Furthermore, the study mapped out the location of these Al Gadaf ropes stones, and the metrical distance beThe study explored the possible tween the traps showed the hunters' plants which could have been used ability to reach and examine these for making such ropes. Elderly in- traps in single day's tour. formants reported that a plant locally A new study known as Al Gadaf was used for makProfessor Altijani adds that some ing such ropes. These ropes were used for restraining camels. Therefore, the foreign expeditions in Dhofar found study suggests that it was quite possi- similar stones, but neither the stones ble that the pre-historic hunters used nor their locations were studied in similar types of plants to make ropes detail. He adds that the Department of Archaeology at SQU is planning for their tethering stones. The role of the tethering stones to conduct similar studies in different as traps, Professor Altijani explains, areas of the Sultanate, especially in was clearly delineated by pre-historic the coastal areas, as these were more rock scenes found in Northern Africa lush and more favourable for the exA huge similarity dating from the seventh millennium istence of animals which could be Professor Altijani goes on to say BC depicting rhinoceros, giraffes, an- hunted by the use of tethering stones. that the rocks found in Al Mudhaibi telopes and buffalos trapped by simi- The Al Wusta region would be the object of this future study. are similar to rocks found in North lar hunting stones. A book and an author Persian literature because of his knowledge of Farsi, and because he has noticed that Arab translation efforts have concerned themselves mostly with translating literatures written in English, ignoring other world languages. An important book Arabic before, the book offers Arab readers a chance to learn about their writings, and about the stages of development in the modern Persian short story from the beginnings to the present time. Difficulties Dr Al Lawati faced some Dr Al Lawati also believes difficulties while dealing with that his book is important for the language of some Iranian the Arab libraries because it ofwriters, especially Sadiq Hidafers a small contribution to fillyat whose language is known Dr Ihsan al Lawati ing what seems to be a big gap for its depth and rich associain their holdings of modern Iranian literature. tions, but he finally came up with an excellent Dr Al Lawati adds that while the Iranians are collection which combines selected narrative making major efforts to translate literary and patterns representing several generations of other texts from Arabic to enrich their libraries, Iranian short story writers. eg translation of the complete works of Gibran This accords with his desire to provide the K Gibran, Nizar Qabbani and others, there is a Arab reader with a panoramic view of the moddearth of counter efforts, to translate new Ira- ern Persian short story and thus fill a deplornian literature into Arabic. able gap in this field. That is why he has read He adds that his book is a small contribution several stories from each generation of writers to a dialogue of cultures whose importance is and selected the best for the Arab reader. known to all. Ancient Arabs were fully aware of the need to draw from the rich Persian herit- Several stages age in arts and literature and they familiarised Dr Al Lawati explains that he worked hard themselves with every available form of it , as to achieve two objectives: first, to select Iraexemplified by Al Gahith, Abu Hilal al Askari, nian narrative texts which represent the variand Abu Hayyan al Tawhidi etc. ous stages of development in the Persian short Nowadays, it has become a necessity for story, though all were taken from the modern the modern generation of Arab authors and period. Hence he started with a text by the real innovators, especially short story writers, to father of the Iranian modern short story, Sadiq read the latest types of stories written by non- Hidayat, then moved to successive writers, and Arabs. This will help them improve their writ- ended with the writings of some young authors ing skills and the quality of their literary work. still struggling to establish their presence in Since most of Iranian authors included in Dr the Iranian literary arena. He believes that this Al Lawati's book have not been translated into variety will give the reader a sense of the artis- Educating for future success while preserving history and heritage tic development of the Persian short story. His second objective was to introduce the reader to the several literary styles in which the stories were written, though the stories are translated into the Arabic. This arises from Dr Al Lawati's conviction that the real task of the translator is to offer an accurate rendering of literary masterpieces from their original languages into others, ie Arabic, keeping the integrity of the source texts, and not to reproduce them in what looks like a new text which lacks any connection with the source text except in terms of general ideas and overall content. ur children are our future. Therefore the research at the College of Education forms the foundation for the future of Oman. Our ultimate mission is to prepare children to assume productive roles in Omani society. Over the last 39 years His Majesty Sultan Qaboos has outlined what such an education should encompass. Students must meet international academic standards while they understand the Muslim religion, the history and heritage of our country and remain committed to the preservation of our rich Omani culture and traditions. Simultaneously, their education should help build a personal ethical character needed to make wise choices in the application of vocational and/or professional skills required for personal and national economic security. Further young people should develop active participation skills vital to protect a free society. These are complex goals requiring the efforts of many agencies working with the College of Education. Since the College began in 1986 we have worked closely with the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Higher Education to prepare and train teachers and professionals needed for the expansion and development of the Omani education system. We cannot educate teachers without understanding the worldwide educational research and then conducting research specifically related to Oman, our teachers and our children. Research conducted by the education faculty examines the needs of children, families, communities and the workplace. We want to know how to best teach every child and adult so that they can achieve personal goals and contribute to the competitive global market conditions that face Oman. At the same time that we are educating our children with the communication skills, technical skills, and world knowledge for the twenty-first century challenges, our schools and universities face the same dilemma parents do. How do we educate modern global citizens who still maintain, appreciate and pass along to their children the rich history and culture of Oman? The research conducted by the international faculty contributes to understanding the problems related to the development of children, education of professionals and education change and reform. For example, faculty research projects explore the effectiveness of recently implemented Basic Education Curriculums, the health and fitness of university students, learning differences, and early childhood education models. A current project examines the integration of Omani cultural topics into English language classes. In this study we found that both students and their teachers were so excited to learn about 41 different aspects of Omani culture that both students and student-teachers improved their English skills significantly. Through the visibility of their research, faculty members have accepted leadership roles in Oman, Gulf region and international research organisations. Faculty share the passion for research with students as exemplified in the recent Autism exhibition presented by a student society. Several funded projects have forged collaborations with other institutions. For example, one Middle East Partnership Initiative (MEPI) includes researchers from the United Arab Emirates, Yale and Northern Kentucky Universities. Another MEPI grant provides funding for a pilot project to make classrooms more focused on student academic growth than on passive learning — or book learning. Students are treated as active participants in their own learning, capable of building knowledge for themselves. The teacher encourages and guides students towards becoming independent and critical thinkers. Ten education faculty members are analysing how best to educate new and old teachers to work effectively in this new environment. Another collaborative funded research venture with the University of Minnesota is a tracer study that examines the self-efficacy of graduates of the College of Education. Results are expected to help us make important decisions regarding how we can improve our courses to ensure the effectiveness of our graduates. These research efforts often culminate in presentations and reports. The College of Education publishes the Educational and Psychological Studies Journal created to share new information about child development, education and learning. The College also helps create new ideas and analysis by hosting research conferences. Four conferences are currently scheduled. They are: International Council for Education on Teaching to be held in Oman this month; Advances in Physical Education, December 2009; Student Centred Learning Conference, March 2010; and Mathematics Teaching, Spring 2011. Research is the foundation of the work at the College of Education as it is the foundation for the education of our children.